Oct 17, 2025·6 min

What Is JWT? A Clear Guide to JSON Web Tokens

Learn what a JWT (JSON Web Token) is, how its three parts work, where it’s used, and the key security tips to avoid common token mistakes.

JWT in simple terms

A JWT (JSON Web Token) is a compact, URL-safe string that represents a set of information (usually about a user or session) in a way that can be passed between systems. You’ll often see it as a long value starting with something like eyJ..., sent in an HTTP header such as Authorization: Bearer <token>.

Why use a token at all?

Traditional logins often rely on server sessions: after you sign in, the server stores session data and gives the browser a session ID cookie. Every request includes that cookie, and the server looks up the session.

With token-based auth, the server can avoid keeping session state for every user request. Instead, the client holds a token (like a JWT) and includes it with API calls. This is popular for APIs because it:

- works well across multiple services (API gateways, microservices)

- fits mobile and single-page apps (SPAs) that call APIs directly

- reduces the need for shared session storage across servers

Important nuance: “stateless” doesn’t mean “no server-side checks ever.” Many real systems still validate tokens against user status, rotating keys, or revocation mechanisms.

Authentication vs authorization (plain English)

- Authentication answers: Who are you? (You sign in and prove your identity.)

- Authorization answers: What are you allowed to do? (You can read invoices, edit projects, access admin pages, etc.)

JWTs commonly carry proof of authentication (you’re signed in) and basic authorization hints (roles, permissions, scopes)—but your server should still enforce authorization rules.

Where JWTs show up

You’ll commonly see JWTs used as access tokens in:

- web APIs

- SPAs

- mobile apps

- systems using OAuth 2.0 or OpenID Connect (OIDC)

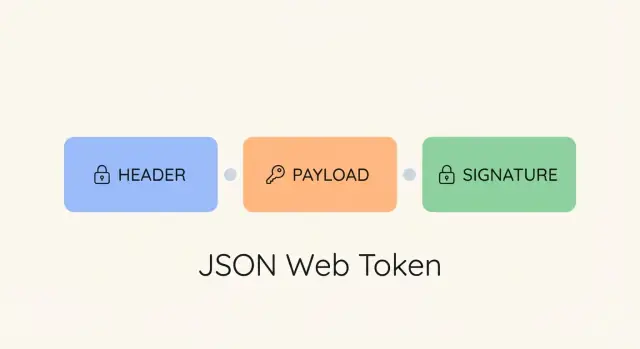

JWT structure: header, payload, and signature

A JWT is a compact string made of three parts, each base64url-encoded and separated by dots:

header.payload.signature

Example (redacted):

eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJzdWIiOiIxMjM0NTY3ODkwIiwiaWF0IjoxNzAwMDAwMDAwfQ.SflKxwRJSMeKKF2QT4fwpMeJf36POk6yJV_adQssw5c…

1) Header

The header describes how the token was created—most importantly the signing algorithm (e.g., HS256, RS256/ES256) and the token type.

Common fields:

typ: often"JWT"(frequently ignored in practice)alg: the signing algorithm usedkid: a key identifier to help the verifier select the right key during rotation

Security note: don’t trust the header blindly. Enforce an allowlist of algorithms you actually use, and do not accept alg: "none".

2) Payload

The payload holds “claims” (fields) about the user and token context: who it’s for, who issued it, and when it expires.

Important: JWTs are not encrypted by default. Base64url encoding makes the token URL-safe; it does not hide the data. Anyone who gets the token can decode the header and payload.

That’s why you should avoid putting secrets (passwords, API keys) or sensitive personal data into a JWT.

3) Signature

The signature is created by signing the header + payload with a key:

- HS256: a shared secret signs and verifies

- RS256/ES256: a private key signs; a public key verifies

The signature provides integrity: it lets the server verify the token wasn’t modified and was minted by a trusted signer. It does not provide confidentiality.

Size considerations

Because a JWT includes header and payload on every request where it’s sent, bigger tokens mean more bandwidth and overhead. Keep claims lean and prefer identifiers over bulky data.

Payload and claims: what you can (and shouldn’t) store

Add JWT Auth to Mobile

Create a Flutter mobile app and connect it to a JWT-secured backend in one workflow.

Claims generally fall into two buckets: registered (standardized names) and custom (your app’s fields).

Common registered claims

iss(issuer): who created the tokensub(subject): who the token is about (often a user ID)aud(audience): who the token is meant for (e.g., a specific API)exp(expiration time): when the token must stop being acceptediat(issued at): when the token was creatednbf(not before): the token should not be accepted before this time

Custom claims: keep them minimal

Include only what the receiving service truly needs to make an authorization decision.

Good examples:

- a stable internal user identifier (

user_id) - a small set of roles/permissions (only if you can keep them current)

- a tenant/organization ID in multi-tenant apps

Avoid “convenience claims” that duplicate lots of profile data. They bloat the token, go stale quickly, and increase impact if the token leaks.

What you should never put in a JWT payload

Because the payload is readable, don’t store:

- passwords, API keys, refresh tokens, or any secret value

- payment details, government IDs, or sensitive personal data

- anything you wouldn’t want copied from a browser, proxy, or log

If you need sensitive information, store it server-side and put only a reference (like an ID) in the token—or use an encrypted token format (JWE) when appropriate.

How the signature works (and what it guarantees)

Signing is not encryption.

- Signing is like sealing a letter: people can read it, but they can verify it wasn’t altered.

- Encryption is like locking the letter in a box: only someone with the key can read it.

When a JWT is issued, the server signs the encoded header + payload. When the token is presented later, the server recomputes the signature and compares it. If someone changes even one character (e.g., "role":"user" to "role":"admin"), verification fails and the token is rejected.

JWT vs OAuth, OpenID Connect, and token types

JWT is a token format. OAuth 2.0 and OpenID Connect (OIDC) are protocols that describe how apps request, issue, and use tokens.

OAuth 2.0 and access/refresh tokens

OAuth 2.0 is mainly about authorization: letting an app access an API on a user’s behalf without sharing the user’s password.

- Access token: presented to an API to prove permission; may be a JWT or an opaque token

- Refresh token: longer-lived token used to obtain new access tokens

Access tokens are typically short-lived (minutes). Short lifetimes limit damage if a token leaks.

OpenID Connect (OIDC) and ID tokens

OIDC adds authentication (who the user is) on top of OAuth 2.0 and introduces an ID token, which is usually a JWT.

- ID token: for the client app to confirm the user’s identity

- Access token: for the API to authorize requests

A key rule: don’t use an ID token to call an API.

If you want more context on practical flows, see /blog/jwt-authentication-flow.

Common JWT authentication flow

Scaffold a Go JWT API

Generate a Go API with JWT middleware, claim checks, and clean request handling.

A typical flow looks like this:

1) Login

The user signs in (email/password, SSO, etc.). If successful, the server creates a JWT (often an access token) with essential claims like subject and expiration.

2) Token issuance

The server signs the token and returns it to the client (web app, mobile app, or another service).

3) API calls

For protected endpoints, the client includes the JWT in the Authorization header:

Authorization: Bearer <JWT>

4) Verification

Before serving the request, the API typically checks:

- signature (integrity + trusted issuer)

exp(not expired)iss(expected issuer)aud(intended for this API)

If all checks pass, the API treats the user as authenticated and applies authorization rules (e.g., record-level permissions).

5) A quick note on clock skew

Because system clocks drift, many systems allow small clock skew when validating time-based claims like exp (and sometimes nbf). Keep the skew small to avoid extending token validity more than intended.

Where to store JWTs safely

Storage choices change what attackers can steal and how easily they can replay a token.

Browser apps: memory vs localStorage vs cookies

In-memory storage (often recommended for SPAs) keeps the access token in JS state. It clears on refresh and reduces “grab it later” theft, but an XSS bug can still read it while the page runs. Pair it with short-lived access tokens and a refresh flow.

localStorage/sessionStorage are easy but risky: any XSS vulnerability can exfiltrate tokens from web storage. If you use them, treat XSS prevention as non-negotiable (CSP, output escaping, dependency hygiene) and keep tokens short-lived.

Secure cookies (often the safest default for web) store tokens in an HttpOnly cookie so JavaScript can’t read them—reducing the impact of XSS token theft. The trade-off is CSRF risk, since browsers attach cookies automatically.

If you use cookies, set:

HttpOnlySecure(HTTPS only)SameSite=LaxorSameSite=Strict(some cross-site flows may needSameSite=None; Secure)

Also consider CSRF tokens for state-changing requests.

Mobile apps: prefer OS secure storage

On iOS/Android, store tokens in platform secure storage (Keychain / Keystore-backed storage). Avoid plain files or preferences. If your threat model includes rooted/jailbroken devices, assume extraction is possible and rely on short-lived tokens and server-side controls.

Least privilege

Limit what a token can do: use minimal scopes/claims, keep access tokens short-lived, and avoid embedding sensitive data.

Common JWT security pitfalls to avoid

JWTs are convenient, but many incidents come from predictable mistakes. Treat a JWT like cash: whoever gets it can often spend it.

1) Overly long expirations

If a token lasts days or weeks, a leak gives an attacker that entire window.

Prefer short-lived access tokens (minutes) and refresh them through a safer mechanism. If you need “remember me,” do it with refresh tokens and server-side controls.

2) Skipping issuer and audience checks

Valid signatures aren’t enough. Verify iss and aud, and validate time-based claims like exp and nbf.

3) Trusting decoded payloads

Decoding is not verification. Always verify the signature on the server and enforce permissions server-side.

4) Algorithm confusion and key mix-ups

- Don’t accept whatever algorithm a token claims. Allowlist expected algorithms.

- Don’t mix up symmetric keys (HS256) with public/private keys (RS256/ES256).

- Minimize blast radius by separating keys per environment and rotating them.

5) Token leakage via URLs, logs, and referrers

Avoid putting JWTs in query params. They can end up in browser history, server logs, analytics tools, and referrer headers.

Use Authorization: Bearer ... instead.

6) No key rotation or revocation plan

Assume keys and tokens can leak. Rotate signing keys, use kid to support smooth rotation, and have a revocation strategy (short expirations + ability to disable accounts/sessions). For storage guidance, see /blog/where-to-store-jwts-safely.

When to use JWT (and when not to)

Own Your Implementation

Keep control by exporting the source code when your JWT setup is ready.

JWTs are useful, but they aren’t automatically the best choice. The real question is whether you benefit from a self-contained token that can be verified without a database lookup on every request.

Good fits for JWT

- Stateless APIs at scale: local verification (signature + expiry) without per-request session lookups

- Multiple services / microservices: shared verification rules and public keys

- SPAs and mobile apps: clients calling APIs directly

- Short-lived access tokens: reduced impact of theft

When JWT is a poor fit

- Instant revocation is a must: sessions are simpler if you need “log out everywhere now” without extra infrastructure

- You need to carry sensitive data: typical JWTs are signed, not encrypted

- Long-lived tokens: they’re high-value and worth stealing

When simple session cookies are better

For traditional server-rendered web apps where straightforward invalidation matters, server-side sessions with HttpOnly cookies are often the simpler, safer default.

Quick decision checklist

Choose JWT if you need stateless verification across services and can keep tokens short-lived.

Avoid JWT if you need instant revocation, plan to store sensitive data in the token, or can use session cookies without friction.

Practical checklist and FAQs

Verification checklist (what to check every time)

- Signature is valid

Verify using the correct key and expected algorithm. Reject invalid signatures—no exceptions.

exp(expiration)

Ensure the token hasn’t expired.

nbf(not before)

If present, ensure the token isn’t being used too early.

aud(audience)

Confirm the token was meant for your API/service.

iss(issuer)

Confirm the token came from the expected issuer.

- Sanity checks (recommended)

Validate token format, enforce maximum size, and reject unexpected claim types to reduce edge-case bugs.

Choosing HS256 vs RS256/ES256

-

HS256 (symmetric key): one shared secret signs and verifies.

- Good for: a single app/API controlled by one team.

- Watch out for: any verifier that has the secret can also mint tokens.

-

RS256 / ES256 (asymmetric keys): private key signs; public key verifies.

- Good for: multiple services verifying tokens; distributing public keys without enabling signing.

- Operational note: rotation is often safer because only the signer holds the private key.

Rule of thumb: if more than one independent system needs to verify tokens (or you don’t fully trust every verifier), prefer RS256/ES256.

Monitoring and logging (without leaking tokens)

- Don’t log raw tokens (headers, cookies, query strings).

- If you need correlation, log a token fingerprint (e.g., a hash) or safe metadata (

iss,aud, and a user ID only if policy allows). - Watch for anomalies: signature failures, spikes in expired tokens, unusual audiences/issuers, and suspicious refresh patterns.

FAQs

Is JWT encrypted?

Not by default. Most JWTs are signed, not encrypted, meaning the contents can be read by anyone who has the token. Use JWE or keep sensitive data out of JWTs.

Can I revoke a JWT?

Not easily if you rely only on self-contained access tokens. Common approaches include short-lived access tokens, deny-lists for high-risk events, or refresh tokens with rotation.

How long should exp be?

As short as your UX and architecture allow. Many APIs use minutes for access tokens, paired with refresh tokens for longer sessions.

Building JWT-protected apps faster with Koder.ai

If you’re implementing JWT auth in a new API or SPA, a lot of the work is repetitive: wiring middleware, validating iss/aud/exp, setting cookie flags, and keeping token handling out of logs.

With Koder.ai, you can vibe-code a web app (React), backend services (Go + PostgreSQL), or a Flutter mobile app through a chat-driven workflow—then iterate in a planning mode, use snapshots and rollback as you refine security, and export the source code when you’re ready. It’s a practical way to accelerate building JWT-based authentication flows while still keeping control over verification logic, key rotation strategy, and deployment/hosting settings (including custom domains).

FAQ

What is a JWT, and where do I usually send it?

A JWT (JSON Web Token) is a compact, URL-safe string that carries claims (data fields) and can be verified by a server. It’s commonly sent on API requests via:

Authorization: Bearer <token>

The key idea: the server can validate the token’s integrity (via its signature) without needing a per-user session record for every request.

How is JWT authentication different from server sessions?

Session auth typically stores state on the server (a session record keyed by a cookie/session ID). With JWT-based auth, the client presents a signed token each request, and the API validates it.

JWTs are popular for APIs and multi-service architectures because verification can be done locally, reducing shared session storage needs.

“Stateless” still often includes server-side checks like revocation lists, user status checks, or key rotation handling.

What are the three parts of a JWT (header, payload, signature)?

A JWT is three Base64URL-encoded parts separated by dots:

header.payload.signature

The header describes how it was signed, the payload contains claims (like sub, exp, aud), and the signature lets the server detect tampering.

Is a JWT encrypted, and can people read what’s inside?

No. Standard JWTs are usually signed, not encrypted.

- Signing proves integrity (it wasn’t modified) and authenticity (issued by a trusted signer).

- Anyone who obtains the token can Base64URL-decode and read the header and payload.

If you need confidentiality, consider JWE (encrypted tokens) or keep sensitive data server-side and store only an identifier in the JWT.

What does the JWT signature guarantee—and what doesn’t it guarantee?

The signature lets the server verify the token hasn’t been altered and was minted by someone with the signing key.

It does not:

- hide payload contents

- prove the user is still active (unless you check)

- automatically revoke tokens before

exp

Treat the token like a credential: if it leaks, it can often be replayed until it expires.

What are `alg` and `kid` in the JWT header, and why do they matter?

alg tells the verifier which algorithm was used (e.g., HS256 vs RS256). kid is a key identifier that helps pick the right verification key during key rotation.

Security rules of thumb:

Which JWT claims should I include in the payload?

Start with standard registered claims and keep custom ones minimal.

Common registered claims:

How do JWT, OAuth 2.0, and OpenID Connect relate (access tokens vs ID tokens)?

JWT is a token format; OAuth 2.0 and OpenID Connect are protocols.

Typical mapping:

- Access token: used to call an API (may be a JWT or opaque).

- ID token (OIDC): used by the client app to confirm identity (usually a JWT).

- : used to obtain new access tokens (often opaque; treat as highly sensitive).

Where should I store JWTs safely in a browser app?

For browser-based apps, common options are:

- In memory: reduces “steal it later” risk, but still vulnerable during an active XSS.

localStorage/sessionStorage: convenient, but any XSS can exfiltrate tokens.- : often safest for web because JS can’t read them, but requires CSRF protections (e.g., + CSRF tokens for state-changing requests).

What checks should my API perform when validating a JWT?

At minimum, validate:

- signature (with the correct key and allowlisted algorithm)

exp(not expired)iss(expected issuer)aud(meant for your API)nbf(if present)

Also add practical guardrails: