Sep 22, 2025·8 min

What Is Kafka and How Is It Used in Modern Systems?

Learn what Apache Kafka is, how topics and partitions work, and where Kafka fits in modern systems for real-time events, logs, and data pipelines.

Learn what Apache Kafka is, how topics and partitions work, and where Kafka fits in modern systems for real-time events, logs, and data pipelines.

Apache Kafka is a distributed event streaming platform. Put simply, it’s a shared, durable “pipe” that lets many systems publish facts about what happened and lets other systems read those facts—quickly, at scale, and in order.

Teams use Kafka when data needs to move reliably between systems without tight coupling. Instead of one application calling another directly (and failing when it’s down or slow), producers write events to Kafka. Consumers read them when they’re ready. Kafka stores events for a configurable period, so systems can recover from outages and even reprocess history.

This guide is for product-minded engineers, data folks, and technical leaders who want a practical mental model of Kafka.

You’ll learn the core building blocks (producers, consumers, topics, brokers), how Kafka scales with partitions, how it stores and replays events, and where it fits in event-driven architecture. We’ll also cover common use cases, delivery guarantees, security basics, operations planning, and when Kafka is (or isn’t) the right tool.

Kafka is easiest to understand as a shared event log: applications write events to it, and other applications read those events later—often in real time, sometimes hours or days after.

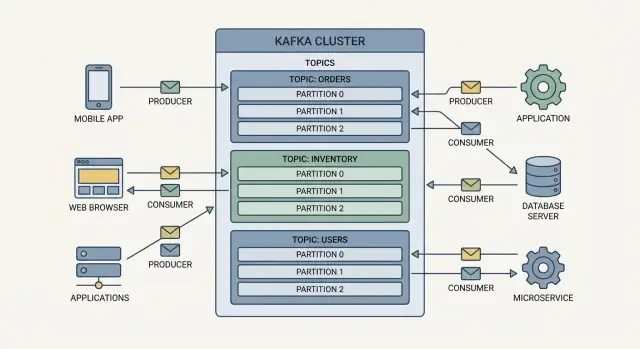

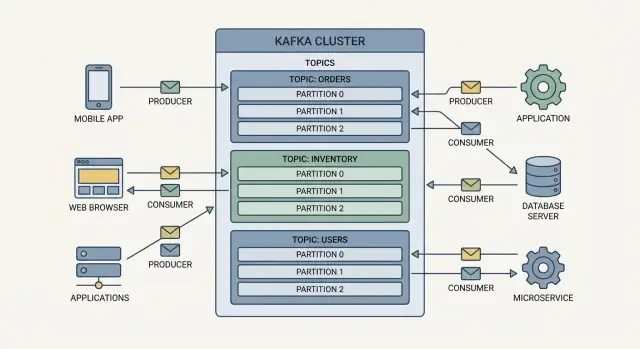

Producers are the writers. A producer might publish an event like “order placed,” “payment confirmed,” or “temperature reading.” Producers don’t send events directly to specific apps—they send them to Kafka.

Consumers are the readers. A consumer might power a dashboard, trigger a shipment workflow, or load data into analytics. Consumers decide what to do with events, and they can read at their own pace.

Events in Kafka are grouped into topics, which are basically named categories. For example:

orders for order-related eventspayments for payment eventsinventory for stock changesA topic becomes the “source of truth” stream for that kind of event, which makes it easier for multiple teams to reuse the same data without building one-off integrations.

A broker is a Kafka server that stores events and serves them to consumers. In practice, Kafka runs as a cluster (multiple brokers working together) so it can handle more traffic and keep running even if a machine fails.

Consumers often run in a consumer group. Kafka spreads reading work across the group, so you can add more consumer instances to scale out processing—without every instance doing the same work.

Kafka scales by splitting work into topics (streams of related events) and then splitting each topic into partitions (smaller, independent slices of that stream).

A topic with one partition can only be read by one consumer at a time within a consumer group. Add more partitions, and you can add more consumers to process events in parallel. That’s how Kafka supports high-volume event streaming and real-time data pipelines without turning every system into a bottleneck.

Partitions also help spread load across brokers. Instead of one machine handling all writes and reads for a topic, multiple brokers can host different partitions and share the traffic.

Kafka guarantees ordering within a single partition. If events A, B, and C are written to the same partition in that order, consumers will read them A → B → C.

Ordering across partitions is not guaranteed. If you need strict ordering for a specific entity (like a customer or order), you typically make sure all events for that entity go to the same partition.

When producers send an event, they can include a key (for example, order_id). Kafka uses the key to consistently route related events to the same partition. That gives you predictable ordering for that key while still letting the overall topic scale across many partitions.

Each partition can be replicated to other brokers. If one broker fails, another broker with a replica can take over. Replication is a major reason Kafka is trusted for mission-critical pub-sub messaging and event-driven systems: it improves availability and supports fault tolerance without requiring every application to build its own failover logic.

A key idea in Apache Kafka is that events aren’t just handed off and forgotten. They’re written to disk in an ordered log, so consumers can read them now—or later. This makes Kafka useful not only for moving data, but also for keeping a durable history of what happened.

When a producer sends an event to a topic, Kafka appends it to storage on the broker. Consumers then read from that stored log at their own pace. If a consumer is down for an hour, the events still exist and can be caught up on once it recovers.

Kafka keeps events according to retention policies:

Retention is configured per topic, which lets you treat “audit trail” topics differently from high-volume telemetry topics.

Some topics are more like a changelog than a historical archive—for example, “current customer settings.” Log compaction keeps at least the most recent event for each key, while older superseded records may be removed. You still get a durable source of truth for the latest state, without unbounded growth.

Because events remain stored, you can replay them to reconstruct state:

In practice, replay is controlled by where a consumer “starts reading” (its offset), giving teams a powerful safety net when systems evolve.

Kafka is built to keep data flowing even when parts of the system fail. It does this with replication, clear rules about who is “in charge” of each partition, and configurable write acknowledgments.

Each topic partition has one leader broker and one or more follower replicas on other brokers. Producers and consumers talk to the leader for that partition.

Followers continuously copy the leader’s data. If the leader goes down, Kafka can promote an up-to-date follower to become the new leader, so the partition remains available.

If a broker fails, any partitions it hosted as leaders become unavailable for a moment. Kafka’s controller (internal coordination) detects the failure and triggers leader election for those partitions.

If at least one follower replica is sufficiently caught up, it can take over as leader and clients resume producing/consuming. If no in-sync replica is available, Kafka may pause writes (depending on your settings) to avoid losing acknowledged data.

Two main knobs shape durability:

At a conceptual level:

To reduce duplicates during retries, teams often combine safer acks with idempotent producers and solid consumer handling (covered later).

Higher safety typically means waiting for more confirmations and keeping more replicas in sync, which can add latency and reduce peak throughput.

Lower latency settings can be fine for telemetry or clickstream data where occasional loss is acceptable, but payments, inventory, and audit logs usually justify the extra safety.

Event-driven architecture (EDA) is a way of building systems where things that happen in the business—an order placed, a payment confirmed, a package shipped—are represented as events that other parts of the system can react to.

Kafka often sits at the center of EDA as the shared “event stream.” Instead of Service A calling Service B directly, Service A publishes an event (for example, OrderCreated) to a Kafka topic. Any number of other services can consume that event and take action—send an email, reserve inventory, start fraud checks—without Service A needing to know they exist.

Because services communicate through events, they don’t have to coordinate request/response APIs for every interaction. This reduces tight dependencies between teams and makes it easier to add new features: you can introduce a new consumer for an existing event without changing the producer.

EDA is naturally asynchronous: producers write events quickly, and consumers process them at their own pace. During traffic spikes, Kafka helps buffer the surge so downstream systems don’t immediately fall over. Consumers can scale out to catch up, and if one consumer goes down temporarily, it can resume from where it left off.

Think of Kafka as the system’s “activity feed.” Producers publish facts; consumers subscribe to the facts they care about. That pattern enables real-time data pipelines and event-driven workflows while keeping services simpler and more independent.

Kafka tends to show up where teams need to move a lot of small “facts that happened” (events) between systems—quickly, reliably, and in a way that multiple consumers can reuse.

Applications often need an append-only history: user sign-ins, permission changes, record updates, or admin actions. Kafka works well as a central stream of these events, so security tools, reporting, and compliance exports can all read the same source without adding load to the production database. Because events are retained for a period of time, you can also replay them to rebuild an audit view after a bug or schema change.

Instead of services calling each other directly, they can publish events like “order created” or “payment received.” Other services subscribe and react in their own time. This reduces tight coupling, helps systems keep working during partial outages, and makes it easier to add new capabilities (for example, fraud checks) by simply consuming the existing event stream.

Kafka is a common backbone for moving data from operational systems into analytics platforms. Teams can stream changes from application databases and deliver them to a warehouse or lake with low delay, while keeping the production app separate from heavy analytical queries.

Sensors, devices, and app telemetry often arrive in spikes. Kafka can absorb bursts, buffer them safely, and let downstream processing catch up—useful for monitoring, alerting, and long-term analysis.

Kafka is more than brokers and topics. Most teams rely on companion tools that make Kafka practical for everyday data movement, stream processing, and operations.

Kafka Connect is Kafka’s integration framework for getting data into Kafka (sources) and out of Kafka (sinks). Instead of building and maintaining one-off pipelines, you run Connect and configure connectors.

Common examples include pulling changes from databases, ingesting SaaS events, or delivering Kafka data to a data warehouse or object storage. Connect also standardizes operational concerns like retries, offsets, and parallelism.

If Connect is for integration, Kafka Streams is for computation. It’s a library you add to your application to transform streams in real time—filtering events, enriching them, joining streams, and building aggregates (like “orders per minute”).

Because Streams apps read from topics and write back to topics, they fit naturally into event-driven systems and can scale by adding more instances.

As multiple teams publish events, consistency matters. Schema management (often via a schema registry) defines what fields an event should have and how they evolve over time. That helps prevent breakages like a producer renaming a field that a consumer depends on.

Kafka is operationally sensitive, so basic monitoring is essential:

Most teams also use management UIs and automation for deployments, topic configuration, and access control policies (see /blog/kafka-security-governance).

Kafka is often described as “durable log + consumers,” but what most teams really care about is: will I process each event once, and what happens when something fails? Kafka gives you building blocks, and you choose the trade-offs.

At-most-once means you might lose events, but you won’t process duplicates. This can happen if a consumer commits its position first and then crashes before finishing the work.

At-least-once means you won’t lose events, but duplicates are possible (for example, the consumer processes an event, crashes, and then reprocesses it after restart). This is the most common default.

Exactly-once aims to avoid both loss and duplicates end-to-end. In Kafka, this typically involves transactional producers and compatible processing (often via Kafka Streams). It’s powerful, but more constrained and requires careful setup.

In practice, many systems embrace at-least-once and add safeguards:

A consumer offset is the position of the last processed record in a partition. When you commit offsets, you’re saying, “I’m done up to here.” Commit too early and you risk loss; commit too late and you increase duplicates after failures.

Retries should be bounded and visible. A common pattern is:

This keeps one “poison message” from blocking an entire consumer group while preserving the data for later fixes.

Kafka often carries business-critical events (orders, payments, user activity). That makes security and governance part of the design, not an afterthought.

Authentication answers “who are you?” Authorization answers “what are you allowed to do?” In Kafka, authentication is commonly done with SASL (for example, SCRAM or Kerberos), while authorization is enforced with ACLs (access control lists) at the topic, consumer group, and cluster levels.

A practical pattern is least privilege: producers can write only to the topics they own, and consumers can read only the topics they need. This reduces accidental data exposure and limits blast radius if credentials leak.

TLS encrypts data as it moves between apps, brokers, and tooling. Without it, events can be intercepted on internal networks, not just the public internet. TLS also helps prevent “man-in-the-middle” attacks by validating broker identities.

When multiple teams share a cluster, guardrails matter. Clear topic naming conventions (for example, <team>.<domain>.<event>.<version>) make ownership obvious and help tooling apply policies consistently.

Pair naming with quotas and ACL templates so one noisy workload doesn’t starve others, and so new services start with safe defaults.

Treat Kafka as a system of record for event history only when you intend to. If events include PII, use data minimization (send IDs instead of full profiles), consider field-level encryption, and document which topics are sensitive.

Retention settings should match legal and business requirements. If policy says “delete after 30 days,” don’t keep 6 months of events “just in case.” Regular reviews and audits keep configurations aligned as systems evolve.

Running Apache Kafka isn’t just “install and forget.” It behaves more like a shared utility: many teams depend on it, and small missteps can ripple out to downstream apps.

Kafka capacity is mostly a math problem you revisit regularly. The biggest levers are partitions (parallelism), throughput (MB/s in and out), and storage growth (how long you retain data).

If traffic doubles, you may need more partitions to spread load across brokers, more disk to hold retention, and more network headroom for replication. A practical habit is to forecast peak write rate and multiply by retention to estimate disk growth, then add buffer for replication and “unexpected success.”

Expect routine work beyond keeping servers up:

Costs are driven by disks, network egress, and the number/size of brokers. Managed Kafka can reduce staffing overhead and simplify upgrades, while self-hosting can be cheaper at scale if you have experienced operators. The trade-off is time-to-recovery and on-call burden.

Teams typically monitor:

Good dashboards and alerts turn Kafka from a “mystery box” into an understandable service.

Kafka is a strong fit when you need to move lots of events reliably, keep them for a while, and let multiple systems react to the same data stream at their own pace. It’s especially useful when data must be replayable (for backfills, audits, or rebuilding a new service) and when you expect more producers/consumers to be added over time.

Kafka tends to shine when you have:

Kafka can be overkill if your needs are simple:

In these cases, the operational overhead (cluster sizing, upgrades, monitoring, on-call) may outweigh the benefits.

Kafka also complements—not replaces—databases (system of record), caches (fast reads), and batch ETL tools (large periodic transformations).

Ask:

If you answer “yes” to most of these, Kafka is usually a sensible choice.

Kafka fits best when you need a shared “source of truth” for real-time event streams: many systems producing facts (orders created, payments authorized, inventory changed) and many systems consuming those facts to power pipelines, analytics, and reactive features.

Start with a narrow, high-value flow—like publishing “OrderPlaced” events for downstream services (email, fraud checks, fulfillment). Avoid turning Kafka into a catch-all queue on day one.

Write down:

Keep early schemas simple and consistent (timestamps, IDs, and a clear event name). Decide whether you’ll enforce schemas up front or evolve carefully over time.

Kafka succeeds when someone owns:

Add monitoring immediately (consumer lag, broker health, throughput, error rates). If you don’t yet have a platform team, start with a managed offering and clear limits.

Produce events from one system, consume them in one place, and prove the loop end-to-end. Only then expand to more consumers, partitions, and integrations.

If you’re trying to move fast from “idea” to a working event-driven service, tools like Koder.ai can help you prototype the surrounding application quickly (React web UI, Go backend, PostgreSQL) and iteratively add Kafka producers/consumers via a chat-driven workflow. It’s especially useful for building internal dashboards and lightweight services that consume topics, with features like planning mode, source code export, deployment/hosting, and snapshots with rollback.

If you’re mapping this into an event-driven approach, see /blog/event-driven-architecture. For planning costs and environments, check /pricing.

Kafka is a distributed event streaming platform that stores events in durable, append-only logs.

Producers write events to topics, and consumers read them independently (often in real time, but also later) because Kafka retains data for a configured period.

Use Kafka when multiple systems need the same stream of events, you want loose coupling, and you may need to replay history.

It’s especially helpful for:

A topic is a named category of events (like orders or payments).

A partition is a slice of a topic that enables:

Kafka guarantees ordering only within a single partition.

Kafka uses the record key (for example, order_id) to consistently route related events to the same partition.

Practical rule: if you need per-entity ordering (all events for an order/customer in sequence), choose a key that represents that entity so those events land in one partition.

A consumer group is a set of consumer instances that share the work for a topic.

Within a group:

If you need two different apps to each get every event, they should use different consumer groups.

Kafka retains events on disk based on topic policies, so consumers can catch up after downtime or reprocess history.

Common retention types:

Retention is per-topic, so high-value audit streams can be kept longer than high-volume telemetry.

Log compaction keeps at least the latest record per key, removing older superseded records over time.

It’s useful for “current state” streams (like settings or profiles) where you care about the latest value per key, not every historical change—while still keeping a durable source of truth for the latest state.

Kafka’s most common end-to-end pattern is at-least-once: you won’t lose events, but duplicates can happen.

To handle this safely:

Offsets are a consumer’s “bookmark” per partition.

If you commit offsets too early, you can lose work on crashes; too late, you’ll reprocess and create duplicates.

A common operational pattern is bounded retries with backoff, then publish failures to a dead-letter topic so one bad record doesn’t block the whole consumer group.

Kafka Connect moves data in/out of Kafka using connectors (sources and sinks) instead of custom pipeline code.

Kafka Streams is a library for transforming and aggregating streams in real time inside your applications (filter, join, enrich, aggregate), reading from topics and writing results back to topics.

Connect is typically for integration; Streams is for computation.