Oct 21, 2025·8 min

Server-Side Rendering (SSR) in Websites: A Clear Guide

Learn what SSR (server-side rendering) means for websites, how it works, and when to use it vs CSR or SSG for SEO, speed, and user experience.

Learn what SSR (server-side rendering) means for websites, how it works, and when to use it vs CSR or SSG for SEO, speed, and user experience.

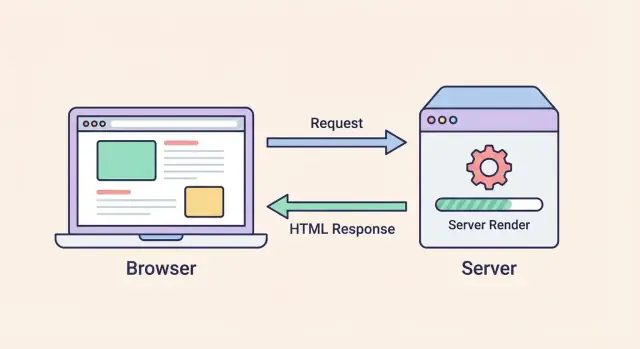

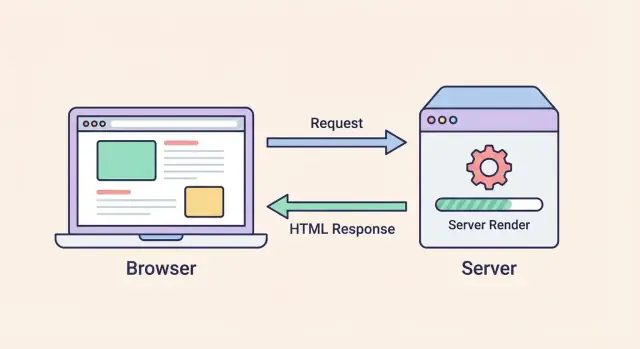

Server-side rendering (SSR) is a way to build web pages where the server generates the HTML for a page at the moment someone requests it, then sends that ready-to-display HTML to the browser.

In plain terms, SSR flips the usual “empty shell first” pattern: instead of shipping a mostly blank page and asking the browser to assemble content immediately, the server does the initial rendering work.

With SSR, people typically see page content sooner—text, headings, and layout can appear quickly because the browser receives real HTML right away.

After that, the page still needs JavaScript to become fully interactive (buttons, menus, forms, dynamic filters). So the common flow is:

This “show content first, then add interactivity” pattern is why SSR comes up so often in performance conversations (especially perceived speed).

SSR doesn’t mean “hosted on a server” (nearly everything is). It’s specifically about where the initial HTML is produced:

So you can use SSR on many hosting setups—traditional servers, serverless functions, or edge runtimes—depending on your framework and deployment.

SSR is just one option among common rendering strategies. Next, we’ll compare SSR vs CSR (client-side rendering) and SSR vs SSG (static site generation), and explain what changes for speed, UX, caching strategy, and SEO outcomes.

SSR means the server prepares the page’s HTML before it reaches the browser. Instead of sending a mostly empty HTML shell and letting the browser build the page from scratch, the server sends a “ready-to-read” version of the page.

/products/123). The browser sends a request to your web server.SSR typically sends HTML plus a JavaScript bundle. The HTML is for immediate display; the JavaScript enables client-side behavior like filters, modals, and “add to cart” interactions.

After the HTML loads, the browser downloads the JavaScript bundle and attaches event handlers to the existing markup. This handoff is what many frameworks refer to as hydration.

With SSR, your server does more work per request—fetching data and rendering markup—so results depend heavily on API/database speed and how well you cache the output.

SSR ships a “ready-to-read” HTML page from the server. That’s great for showing content quickly, but it doesn’t automatically make the page interactive.

A very common setup is:

SSR can improve how quickly people can see the page, while hydration is what makes the page behave like an app.

Hydration is the process where the client-side JavaScript takes over the static HTML and attaches interactivity: click handlers, form validation, menus, dynamic filters, and any stateful UI.

That extra step costs CPU time and memory on the user’s device. On slower phones or busy tabs, hydration can be noticeably delayed—even if the HTML arrived fast.

When JavaScript is slow to load, users may see content but experience “dead” UI for a moment: buttons don’t respond, menus don’t open, and inputs may lag.

If JavaScript fails entirely (blocked, network error, script crash), SSR still means the core content can appear. But app-like features that rely on JavaScript won’t work unless you’ve designed fallbacks (for example, links that navigate normally, forms that submit without client code).

SSR is about where HTML is generated. Many SSR sites still ship substantial JavaScript—sometimes almost as much as a CSR app—because interactivity still needs code running in the browser.

Server-side rendering (SSR) and client-side rendering (CSR) can produce the same-looking page, but the order of work is different—and that changes how fast the page feels.

With CSR, the browser usually downloads a JavaScript bundle first, then runs it to build the HTML. Until that work finishes, users may see a blank screen, a spinner, or a “shell” UI. That can make the first view feel slow even if the app is powerful once loaded.

With SSR, the server sends ready-to-display HTML right away. Users can see headings, text, and layout sooner, which often improves perceived speed—especially on slower devices or networks.

CSR often shines after the initial load: navigation between screens can be very fast because the app is already running in the browser.

SSR can feel faster at first, but the page still needs JavaScript to become fully interactive (buttons, menus, forms). If the JavaScript is heavy, users might see content quickly but still experience a short delay before everything responds.

SSR (Server-Side Rendering) and SSG (Static Site Generation) can look similar to visitors—both often send real HTML to the browser. The key difference is when that HTML is created.

With SSG, your site generates HTML ahead of time—usually during a build step when you deploy. Those files can be served from a CDN like any other static asset.

That makes SSG:

The trade-off is freshness: if content changes often, you either rebuild and redeploy, or use incremental techniques to update pages.

With SSR, the server generates the HTML on every request (or at least when the cache misses). This is useful when content must reflect the latest data for that specific visitor or moment.

SSR is a good fit for:

The trade-off is build time vs request time: you avoid long rebuilds for changing content, but you introduce per-request work on the server—which affects TTFB and operating cost.

Many modern sites are hybrid: marketing pages and documentation are SSG, while account areas or search results are SSR.

A practical way to decide is to ask:

Choosing rendering strategy per route often gives the best balance of speed, cost, and up-to-date content.

Server-side rendering often improves SEO because search engines can see real, meaningful content as soon as they request a page. Instead of receiving an almost-empty HTML shell that needs JavaScript to fill in, crawlers get full text, headings, and links right away.

Earlier content discovery. When the HTML already contains your page content, crawlers can index it faster and more consistently—especially for large sites where crawl budgets and timing matter.

More reliable rendering. Modern search engines can execute JavaScript, but it isn’t always immediate or predictable. Some bots render slowly, postpone JavaScript execution, or skip it under resource constraints. SSR reduces your dependence on “hope the crawler runs my JS.”

On-page SEO essentials. SSR makes it easier to output key signals in the initial HTML response, such as:

Content quality and intent. SSR can help search engines access your content, but it can’t make that content useful, original, or aligned with what people search for.

Site structure and internal linking. Clear navigation, logical URL structure, and strong internal links still matter for discoverability and ranking.

Technical SEO hygiene. Issues like thin pages, duplicate URLs, broken canonicals, blocked resources, or incorrect noindex rules can still prevent good outcomes—even with SSR.

Think of SSR as improving your crawl-and-render reliability. It’s a strong foundation, not a shortcut to rankings.

Performance talk around SSR usually boils down to a few key metrics—and one user feeling: “Did the page show up quickly?” SSR can improve what people see early, but it can also shift work to the server and to hydration.

TTFB (Time to First Byte) is how long it takes the server to start sending anything back. With SSR, TTFB often becomes more important because the server may need to fetch data and render HTML before it can respond. If your server is slow, SSR can actually make TTFB worse.

FCP (First Contentful Paint) is when the browser first paints any content (text, background, etc.). SSR often helps FCP because the browser receives ready-to-display HTML instead of an empty shell.

LCP (Largest Contentful Paint) is when the biggest “main” element (often a hero heading, image, or product title) becomes visible. SSR can help LCP too—if the HTML arrives quickly and critical CSS/assets don’t block rendering.

SSR adds server work on every request (unless cached). Two common bottlenecks are:

A practical takeaway: SSR performance is often less about the framework and more about your data path. Reducing API round-trips, using faster queries, or precomputing parts of the page can make a bigger difference than tweaking front-end code.

SSR is great at “first view” speed: users may see content sooner, scroll sooner, and feel like the site is responsive. But hydration still needs JavaScript to wire up buttons, menus, and forms.

That creates a trade-off:

The fastest SSR is often cached SSR. If you can cache the rendered HTML (at the CDN, reverse proxy, or app level), you avoid re-rendering and repeated data fetching on every request—improving TTFB and, in turn, LCP.

The key is choosing a caching strategy that matches your content (public vs. personalized) so you get speed without accidentally serving the wrong user’s data.

SSR can feel slow if every request forces your server to render HTML from scratch. Caching fixes that—but only if you’re careful about what’s safe to cache.

Most SSR stacks end up with multiple caches:

A cached SSR response is only correct if the cache key matches all the things that change the output. Besides the URL path, common variations include:

HTTP helps here: use the Vary header when output changes based on request headers (for example Vary: Accept-Language). Be cautious with Vary: Cookie—it can destroy cache hit rates.

Use Cache-Control to define behavior:

public, max-age=0, s-maxage=600 (cache at CDN/proxy for 10 minutes)stale-while-revalidate=30 (serve slightly old HTML while refreshing in the background)Never cache HTML that includes private user data unless the cache is strictly per-user. A safer pattern is: cache a public shell SSR response, then fetch personalized data after load (or render it server-side but mark the response private, no-store). One mistake here can leak account details across users.

SSR can make pages feel faster and more complete on first load, but it also shifts complexity back to your server. Before committing, it’s worth knowing what can go wrong—and what tends to surprise teams.

With SSR, your site isn’t just static files on a CDN. You now have a server (or serverless functions) rendering HTML on demand.

That means you’re responsible for runtime configuration, safer deployments (rollbacks matter), and monitoring real-time behavior: error rates, slow requests, memory usage, and dependency failures. A bad release can break every page request immediately, not just a single bundle download.

SSR often increases compute per request. Even if HTML rendering is quick, it’s still work your servers must do for every visit.

Compared to purely static hosting, costs can rise due to:

Because SSR happens at request time, you can hit edge cases such as:

If your SSR code calls an external API, one slow dependency can turn into a slow homepage. This is why timeouts, fallbacks, and caching are not optional.

A common developer pitfall is when the server renders HTML that doesn’t exactly match what the browser renders during hydration. The result can be warnings, flicker, or broken interactivity.

Typical causes include random values, timestamps, user-specific data, or browser-only APIs during the initial render without guarding them properly.

Choosing “SSR” usually means choosing a framework that can render HTML on the server and then make it interactive in the browser. Here are common options and the terms you’ll see around them.

Next.js (React) is a default choice for many teams. It supports SSR per route, static generation, streaming, and multiple deployment targets (Node servers, serverless, and edge).

Nuxt (Vue) offers a similar experience for Vue teams, with file-based routing and flexible rendering modes.

Remix (React) leans into web standards and nested routing. It’s often chosen for data-heavy apps where routing and data loading should be tightly coupled.

SvelteKit (Svelte) combines SSR, static output, and adapters for different hosts, with a lightweight feel and straightforward data loading.

Choose based on your team’s UI library, how you want to host (Node server, serverless, edge), and how much control you need over caching, streaming, and data loading.

If you want a faster way to experiment before committing to a full SSR stack, a platform like Koder.ai can help you prototype a production-shaped app from a chat interface—typically with a React frontend and a Go + PostgreSQL backend—then iterate with features like planning mode, snapshots, and rollback. For teams evaluating SSR trade-offs, that “prototype-to-deploy” loop can make it easier to measure real TTFB/LCP impact instead of guessing.

SSR is most valuable when you need pages to feel ready quickly and be reliably readable by search engines and social preview bots. It’s not a magic speed button, but it can be the right trade-off when first impressions matter.

SSR tends to shine for:

If your pages are publicly accessible and you care about discoverability, SSR is usually worth evaluating.

SSR can be a poor fit when:

In those cases, client-side rendering or a hybrid approach often keeps infrastructure simpler.

Consider SSR when these are true:

SSR can be a great fit, but it’s easiest to succeed when you decide with real constraints in mind—not just “faster pages.” Use this checklist to pressure-test the choice before you invest.

Measure a baseline in production-like conditions, then compare after a prototype:

Set alerts and dashboards for:

If the checklist raises concerns, evaluate a hybrid approach (SSR + SSG): pre-render stable pages with SSG, use SSR only where freshness or personalization truly matters. This often gives the best speed/complexity trade-off.

If you do decide to prototype, keep the loop tight: ship a minimal route in SSR, add caching, then measure. Tools that streamline building and deployment can help here—for example, Koder.ai supports deploying and hosting apps (with custom domains and source code export available), which makes it easier to validate SSR performance and rollout/rollback safely while you iterate.

SSR (server-side rendering) means your server generates the page’s HTML when a user requests a URL, then sends that ready-to-display HTML to the browser.

It’s different from “being hosted on a server” (almost everything is). SSR specifically describes where the initial HTML is produced: on the server per request (or per cache miss).

A typical SSR flow looks like this:

/products/123).The big UX difference is that users can often read content sooner because real HTML arrives first.

SSR primarily improves how fast users can see content, but JavaScript is still required for app-like behavior.

Most SSR sites ship:

So SSR is usually “content first, interactivity second,” not “no JavaScript.”

Hydration is the browser-side step where your JavaScript “activates” the server-rendered HTML.

Practically, hydration:

On slower devices or with large bundles, users may see content quickly but experience a short “dead UI” period until hydration finishes.

CSR (client-side rendering) typically downloads JavaScript first and then builds the HTML in the browser, which can mean a blank/shell UI until JS finishes.

SSR sends ready-to-display HTML first, which often improves perceived speed for first-time visits.

A common rule of thumb:

SSG (static site generation) creates HTML at build/deploy time and serves it like static files—very cacheable and predictable under load.

SSR creates HTML at request time (or on cache miss), which helps when pages must be fresh, personalized, or depend on request context.

Many sites mix both: SSG for stable marketing/docs, SSR for search results, inventory, or user-context pages.

SSR can help SEO by putting meaningful content and metadata directly in the initial HTML response, which makes crawling and indexing more reliable.

SSR helps with:

SSR does not fix:

The most relevant metrics are:

SSR performance often depends more on your (API/DB latency, round trips) and than on the UI framework.

Caching SSR output is powerful, but you must avoid serving one user’s HTML to another.

Practical safeguards:

Common SSR pitfalls include:

Cache-Control (e.g., s-maxage, stale-while-revalidate).Vary where appropriate (e.g., Vary: Accept-Language), and be cautious with Vary: Cookie.private, no-store or cache only per-user (if you truly must).When in doubt, cache a public shell and fetch personalized details after load.

Mitigations: set timeouts/fallbacks, reduce data round trips, add caching layers, and keep server/client renders deterministic.