May 01, 2025·8 min

Why Lua Excels for Embedding and Game Scripting Tasks

Explore why Lua is ideal for embedding and game scripting: tiny footprint, fast runtime, simple C API, coroutines, safety options, and great portability.

Explore why Lua is ideal for embedding and game scripting: tiny footprint, fast runtime, simple C API, coroutines, safety options, and great portability.

“Embedding” a scripting language means your application (for example, a game engine) ships with a language runtime inside it, and your code calls into that runtime to load and run scripts. The player doesn’t start Lua separately, install it, or manage packages; it’s simply part of the game.

By contrast, standalone scripting is when a script runs in its own interpreter or tool (like running a script from a command line). That can be great for automation, but it’s a different model: your app is not the host; the interpreter is.

Games are a mix of systems that need different iteration speeds. Low-level engine code (rendering, physics, threading) benefits from C/C++ performance and strict control. Gameplay logic, UI flows, quests, item tuning, and enemy behaviors benefit from being editable quickly without rebuilding the whole game.

Embedding a language lets teams:

When people call Lua a “language of choice” for embedding, it usually doesn’t mean it’s perfect for everything. It means it’s proven in production, has predictable integration patterns, and makes practical tradeoffs that fit shipping games: a small runtime, strong performance, and a C-friendly API that’s been exercised for years.

Next, we’ll look at Lua’s footprint and performance, how C/C++ integration typically works, what coroutines enable for gameplay flow, and how tables/metatables support data-driven design. We’ll also cover sandboxing options, maintainability, tooling, comparisons to other languages, and a checklist of best practices for deciding whether Lua fits your engine.

Lua’s interpreter is famously small. That matters in games because every extra megabyte affects download size, patch time, memory pressure, and even certification constraints on some platforms. A compact runtime also tends to start fast, which helps for editor tools, scripting consoles, and quick iteration workflows.

Lua’s core is lean: fewer moving parts, fewer hidden subsystems, and a memory model you can reason about. For many teams, this translates to predictable overhead—your engine and content typically dominate memory, not the scripting VM.

Portability is where a small core really pays off. Lua is written in portable C and is commonly used on desktop, consoles, and mobile. If your engine already builds C/C++ across targets, Lua usually fits into that same pipeline without special tooling. That reduces platform surprises, like different behavior or missing runtime features.

Lua is typically built as a small static library or compiled directly into your project. There’s no heavy runtime to install and no large dependency tree to keep aligned. Fewer external pieces means fewer version conflicts, fewer security update cycles, and fewer places builds can break—especially valuable for long-lived game branches.

A lightweight scripting runtime isn’t just about shipping. It enables scripts in more places—editor utilities, mod tools, UI logic, quest logic, and automated tests—without feeling like you’re “adding a whole platform” to your codebase. That flexibility is a big reason teams keep reaching for Lua when embedding a language inside a game engine.

Game teams rarely need scripts to be “the fastest code in the project.” They need scripts to be fast enough that designers can iterate without the frame rate collapsing, and predictable enough that spikes are easy to diagnose.

For most titles, “fast enough” is measured in milliseconds per frame budget. If your scripting work stays in the slice allotted to gameplay logic (often a fraction of the total frame), players won’t notice. The goal isn’t to beat optimized C++; it’s to keep per-frame script work stable and avoid sudden garbage or allocation bursts.

Lua runs code inside a small virtual machine. Your source is compiled to bytecode, then executed by the VM. In production, this enables shipping precompiled chunks, reducing parsing overhead at runtime, and keeping execution relatively consistent.

Lua’s VM is also tuned for the operations scripts do constantly—function calls, table access, and branching—so typical gameplay logic tends to run smoothly even on constrained platforms.

Lua is commonly used for:

Lua is usually not used for hot inner loops like physics integration, animation skinning, pathfinding core kernels, or particle simulation. Those stay in C/C++ and are exposed to Lua as higher-level functions.

A few habits keep Lua fast in real projects:

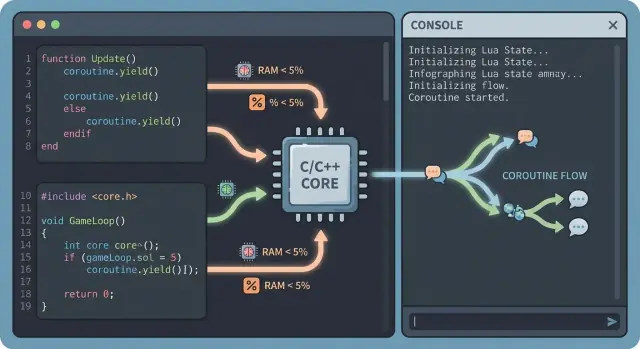

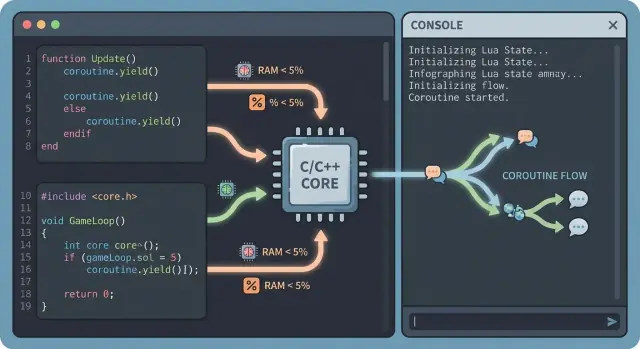

Lua earned its reputation in game engines largely because its integration story is simple and predictable. Lua ships as a small C library, and the Lua C API is designed around a clear idea: your engine and scripts talk through a stack-based interface.

On the engine side, you create a Lua state, load scripts, and call functions by pushing values onto a stack. It’s not “magic,” which is exactly why it’s dependable: you can see every value crossing the boundary, validate types, and decide how errors are handled.

A typical call flow is:

Going from C/C++ → Lua is great for scripted decisions: AI choices, quest logic, UI rules, or ability formulas.

Going from Lua → C/C++ is ideal for engine actions: spawning entities, playing audio, querying physics, or sending network messages. You expose C functions to Lua, often grouped into a module-style table:

lua_register(L, "PlaySound", PlaySound_C);

From the scripting side, the call is natural:

PlaySound("explosion_big")

Manual bindings (handwritten glue) stay small and explicit—perfect when you only expose a curated API surface.

Generators (SWIG-style approaches or custom reflection tools) can speed up large APIs, but they may expose too much, lock you into patterns, or produce confusing error messages. Many teams mix both: generators for data types, manual bindings for gameplay-facing functions.

Well-structured engines rarely dump “everything” into Lua. Instead, they expose focused services and component APIs:

This division keeps scripts expressive while the engine retains control over performance-critical systems and guardrails.

Lua coroutines are a natural match for gameplay logic because they let scripts pause and resume without freezing the whole game. Instead of splitting a quest or cutscene into dozens of state flags, you can write it as a straight, readable sequence—and yield control back to the engine whenever you need to wait.

Most gameplay tasks are inherently step-by-step: show a line of dialogue, wait for player input, play an animation, wait 2 seconds, spawn enemies, and so on. With coroutines, each of those wait points is just a yield(). The engine resumes the coroutine later when the condition is met.

Coroutines are cooperative, not preemptive. That’s a feature for games: you decide exactly where a script can pause, which makes behavior predictable and avoids many thread-safety headaches (locks, races, shared data contention). Your game loop stays in charge.

A common approach is to provide engine functions like wait_seconds(t), wait_event(name), or wait_until(predicate) that internally yield. The scheduler (often a simple list of running coroutines) checks timers/events each frame and resumes whichever coroutine is ready.

The result: scripts that feel async, but remain easy to reason about, debug, and keep deterministic.

Lua’s “secret weapon” for game scripting is the table. A table is a single, lightweight structure that can act like an object, a dictionary, a list, or a nested configuration blob. That means you can model gameplay data without inventing a new format or writing piles of parsing code.

Instead of hard-coding every parameter in C++ (and recompiling), designers can express content as plain tables:

Enemy = {

id = "slime",

hp = 35,

speed = 2.4,

drops = { "coin", "gel" },

resist = { fire = 0.5, ice = 1.2 }

}

This scales well: add a new field when you need it, leave it out when you don’t, and keep older content working.

Tables make it natural to prototype gameplay objects (weapons, quests, abilities) and tune values in-place. During iteration, you can swap a behavior flag, tweak a cooldown, or add an optional sub-table for special rules without touching engine code.

Metatables let you attach shared behavior to many tables—like a lightweight class system. You can define defaults (e.g., missing stats), computed properties, or simple inheritance-like reuse, while keeping the data format readable for content authors.

When your engine treats tables as the primary content unit, mods become straightforward: a mod can override a table field, extend a drop list, or register a new item by adding another table. You end up with a game that’s easier to tune, easier to extend, and friendlier to community content—without turning your scripting layer into a complicated framework.

Embedding Lua means you’re responsible for what scripts can touch. Sandboxing is the set of rules that keeps scripts focused on the gameplay APIs you expose, while preventing access to the host machine, sensitive files, or engine internals you didn’t mean to share.

A practical baseline is to start with a minimal environment and add capabilities intentionally.

io and os entirely to prevent file and process access.loadfile, and if you allow load, only accept pre-approved sources (e.g., packaged content) rather than raw user input.Instead of exposing the whole global table, provide a single game (or engine) table with the functions you want designers or modders to call.

Sandboxing is also about preventing scripts from freezing a frame or exhausting memory.

Treat first-party scripts differently from mods.

Lua is often introduced for speed of iteration, but its long-term value shows up when a project survives months of refactors without constant script breakage. That requires a few deliberate practices.

Treat the Lua-facing API like a product interface, not a direct mirror of your C++ classes. Expose a small set of gameplay services (spawn, play sound, query tags, start dialogue) and keep engine internals private.

A thin, stable API boundary reduces churn: you can reorganize engine systems while keeping function names, argument shapes, and return values consistent for designers.

Breaking changes are inevitable. Make them manageable by versioning your script modules or the exposed API:

Even a lightweight API_VERSION constant returned to Lua can help scripts choose the right path.

Hot-reload is most reliable when you reload code but keep runtime state under engine control. Reload scripts that define abilities, UI behavior, or quest rules; avoid reloading objects that own memory, physics bodies, or network connections.

A practical approach is to reload modules, then re-bind callbacks on existing entities. If you need deeper resets, provide explicit reinitialize hooks rather than relying on module side effects.

When a script fails, the error should identify:

Route Lua errors into the same in-game console and log files as engine messages, and keep stack traces intact. Designers can fix issues faster when the report reads like an actionable ticket, not a cryptic crash.

Lua’s biggest tooling advantage is that it fits into the same iteration loop as your engine: load a script, run the game, inspect results, tweak, reload. The trick is making that loop observable and repeatable for the whole team.

For day-to-day debugging, you want three basics: set breakpoints in script files, step line-by-line, and watch variables as they change. Many studios implement this by exposing Lua’s debug hooks to an editor UI, or by integrating an off-the-shelf remote debugger.

Even without a full debugger, add developer affordances:

Script performance problems are rarely “Lua is slow”; they’re usually “this function runs 10,000 times per frame.” Add lightweight counters and timers around script entry points (AI ticks, UI updates, event handlers), then aggregate by function name.

When you find a hotspot, decide whether to:

Treat scripts like code, not content. Run unit tests for pure Lua modules (game rules, math, loot tables), plus integration tests that boot a minimal game runtime and execute key flows.

For builds, package scripts in a predictable way: either plain files (easy patching) or a bundled archive (fewer loose assets). Whichever you choose, validate at build time: syntax check, required module presence, and a simple “load every script” smoke test to catch missing assets before shipping.

If you’re building internal tooling around scripts—like a web-based “script registry,” profiling dashboards, or a content validation service—Koder.ai can be a fast way to prototype and ship those companion apps. Because it generates full-stack applications via chat (commonly React + Go + PostgreSQL) and supports deployment, hosting, and snapshots/rollback, it’s well-suited for iterating on studio tools without committing months of engineering time up front.

Choosing a scripting language is less about “best overall” and more about what fits your engine, your deployment targets, and your team. Lua tends to win when you need a script layer that is lightweight, fast enough for gameplay, and straightforward to embed.

Python is excellent for tools and pipelines, but it’s a heavier runtime to ship inside a game. Embedding Python also tends to pull in more dependencies and has a more complex integration surface.

Lua, by contrast, is typically much smaller in memory footprint and easier to bundle across platforms. It also has a C API designed for embedding from day one, which often makes calling into engine code (and vice versa) simpler to reason about.

On speed: Python can be plenty fast for high-level logic, but Lua’s execution model and common usage patterns in games often make it a better fit when scripts run frequently (AI ticks, ability logic, UI updates).

JavaScript can be attractive because many developers already know it, and modern JS engines are extremely fast. The tradeoff is runtime weight and integration complexity: shipping a full JS engine can be a bigger commitment, and the binding layer can become a project of its own.

Lua’s runtime is much lighter, and its embedding story is usually more predictable for game-engine style host applications.

C# offers a productive workflow, great tooling, and a familiar object-oriented model. If your engine already hosts a managed runtime, iteration speed and developer experience can be fantastic.

But if you’re building a custom engine (especially for constrained platforms), hosting a managed runtime can increase binary size, memory usage, and startup costs. Lua often delivers good-enough ergonomics with a smaller runtime footprint.

If your constraints are tight (mobile, consoles, custom engine), and you want an embedded scripting language that stays out of the way, Lua is hard to beat. If your priority is developer familiarity or you already depend on a specific runtime (JS or .NET), aligning with your team’s strengths may outweigh Lua’s footprint and embedding advantages.

Embedding Lua goes best when you treat it like a product inside your engine: a stable interface, predictable behavior, and guardrails that keep content creators productive.

Expose a small set of engine services rather than raw engine internals. Typical services include time, input, audio, UI, spawning, and logging. Add an event system so scripts react to gameplay (“OnHit”, “OnQuestCompleted”) instead of constantly polling.

Keep data access explicit: a read-only view for configuration, and a controlled write path for state changes. This makes it easier to test, secure, and evolve.

Use Lua for rules, orchestration, and content logic; keep heavy work (pathfinding, physics queries, animation evaluation, large loops) in native code. A good rule: if it runs every frame for many entities, it probably should be C/C++ with a Lua-friendly wrapper.

Establish conventions early: module layout, naming, and how scripts signal failure. Decide whether errors should throw, return nil, err, or emit events.

Centralize logging and make stack traces actionable. When a script fails, include entity ID, level name, and the last event processed.

Localization: keep strings out of logic where possible, and route text through a localization service.

Save/load: version your saved data and keep script state serializable (tables of primitives, stable IDs).

Determinism (if needed for replays or netcode): avoid nondeterministic sources (wall-clock time, unordered iteration) and ensure random number use is controlled via seeded RNG.

For implementation details and patterns, see /blog/scripting-apis and /docs/save-load.

Lua earns its reputation in game engines because it’s simple to embed, fast enough for most gameplay logic, and flexible for data-driven features. You can ship it with minimal overhead, integrate it cleanly with C/C++, and structure gameplay flow with coroutines without forcing your engine into a heavy runtime or complex toolchain.

Use this as a quick evaluation pass:

If you answered “yes” to most of these, Lua is a strong candidate.

wait(seconds), wait_event(name)) and integrate it with your main loop.If you want a practical starting point, see /blog/best-practices-embedding-lua for a minimal embedding checklist you can adapt.

Embedding means your application includes the Lua runtime and drives it.

Standalone scripting runs scripts in an external interpreter/tool (e.g., from a terminal), and your app is just a consumer of outputs.

Embedded scripting flips the relationship: the game is the host, and scripts execute inside the game’s process with game-owned timing, memory rules, and exposed APIs.

Lua is often chosen because it fits shipping constraints:

Typical wins are iteration speed and separation of concerns:

Keep scripts orchestrating and keep heavy kernels native.

Good Lua use cases:

Avoid putting these in Lua hot loops:

A few practical habits help avoid frame-time spikes:

Most integrations are stack-based:

For Lua → engine calls, you expose curated C/C++ functions (often grouped into a module table like engine.audio.play(...)).

Coroutines let scripts pause/resume cooperatively without blocking the game loop.

Common pattern:

wait_seconds(t) / wait_event(name)This keeps quest/cutscene logic readable without sprawling state flags.

Start from a minimal environment and add capabilities intentionally:

Treat the Lua-facing API like a stable product interface:

API_VERSION helps)ioosloadfile (and restrict load) to prevent arbitrary code injectiongame/engine) instead of full globals