Sep 06, 2025·8 min

When to Stop Vibe Coding and Harden Systems for Production

Learn the signs a prototype is becoming a real product, plus a practical checklist to harden reliability, security, testing, and operations for production.

Learn the signs a prototype is becoming a real product, plus a practical checklist to harden reliability, security, testing, and operations for production.

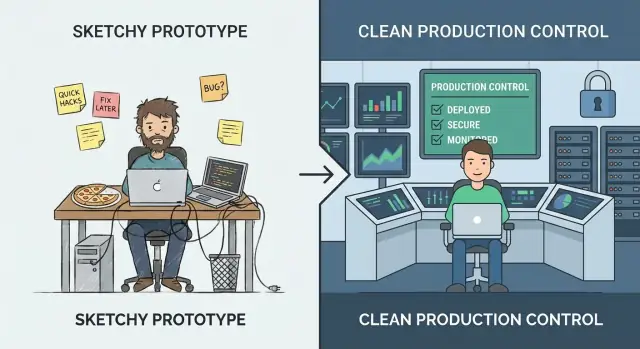

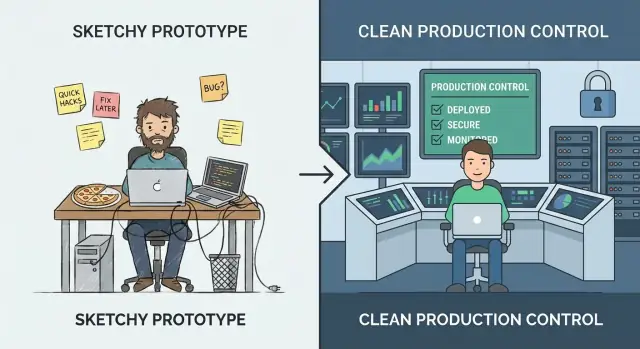

“Vibe coding” is the phase where speed beats precision. You’re experimenting, learning what users actually want, and trying ideas that might not survive the week. The goal is insight: validate a workflow, prove a value proposition, or confirm the data you need even exists. In this mode, rough edges are normal—manual steps, weak error handling, and code optimized to get to “working” fast.

“Production hardening” is different. It’s the work of making behavior predictable under real usage: messy inputs, partial outages, peak traffic, and people doing things you didn’t anticipate. Hardening is less about adding features and more about reducing surprises—so the system fails safely, recovers cleanly, and is understandable to the next person who has to operate it.

If you harden too early, you can slow learning. You may invest in scalability, automation, or polished architecture for a product direction that changes next week. That’s expensive, and it can make a small team feel stuck.

If you harden too late, you create risk. The same shortcuts that were fine for a demo become customer-facing incidents: data inconsistency, security gaps, and downtime that damages trust.

A practical approach is to keep experimenting while hardening the “thin waist” of the system: the few key paths that must be dependable (sign-up, payments, data writes, critical integrations). You can still iterate quickly on peripheral features—just don’t let prototype assumptions govern the parts that real users rely on every day.

This is also where tooling choices matter. Platforms built for rapid iteration can help you stay in “vibe” mode without losing the ability to professionalize later. For example, Koder.ai is designed for vibe-coding via chat to create web, backend, and mobile apps, but it also supports source code export, deployment/hosting, custom domains, and snapshots/rollback—features that map directly to the “thin waist” mindset (ship fast, but protect critical paths and recover quickly).

Vibe coding shines when you’re trying to learn quickly: can this idea work at all? The mistake is assuming the same habits will hold up once real people (or real business processes) depend on the output.

A useful way to decide what to harden is to name the stage you’re in:

As you move right, the question shifts from “Does it work?” to “Can we trust it?” That adds expectations like predictable performance, clear error handling, auditability, and the ability to roll back changes. It also forces you to define ownership: who is on the hook when something breaks?

Bugs fixed during idea/demo are cheap because you’re changing code no one relies on. After launch, the same bug can trigger support time, data cleanup, customer churn, or missed deadlines. Hardening isn’t perfectionism—it’s reducing the blast radius of inevitable mistakes.

An internal tool that triggers invoices, routes leads, or controls access is already production if the business depends on it. If a failure would stop work, expose data, or create financial risk, treat it like production—even if only 20 people use it.

A prototype is allowed to be fragile. It proves an idea, unlocks a conversation, and helps you learn quickly. The moment real people start relying on it, the cost of “quick fixes” rises—and the risks shift from inconvenient to business-impacting.

Your audience is changing. If user count is steadily climbing, you’ve added paid customers, or you’ve signed anything with uptime/response expectations, you’re no longer experimenting—you’re delivering a service.

The data got more sensitive. The day your system starts touching PII (names, emails, addresses), financial data, credentials, or private files, you need stronger access controls, audit trails, and safer defaults. A prototype can be “secure enough for a demo.” Real data can’t.

Usage turns routine or mission-critical. When the tool becomes part of someone’s daily workflow—or when failures block orders, reporting, onboarding, or customer support—downtime and weird edge cases stop being acceptable.

Other teams depend on your outputs. If internal teams are building processes around your dashboards, exports, webhooks, or APIs, every change becomes a potential breaking change. You’ll feel pressure to keep behavior consistent and communicate changes.

Breaks become recurring. A steady stream of “it broke” messages, Slack pings, and support tickets is a strong indicator you’re spending more time reacting than learning. That’s your cue to invest in stability rather than more features.

If a one-hour outage would be embarrassing, you’re nearing production. If it would be expensive—lost revenue, breached promises, or damaged trust—you’re already there.

If you’re arguing about whether the app is “ready,” you’re already asking the wrong question. The better question is: what’s the cost of being wrong? Production hardening isn’t a badge of honor—it’s a response to risk.

Write down what failure looks like for your system. Common categories:

Be specific. “Search takes 12 seconds for 20% of users during peak” is actionable; “performance issues” isn’t.

You don’t need perfect numbers—use ranges.

If the impact feels hard to quantify, ask: Who gets paged? Who apologizes? Who pays?

Most prototype-to-production failures cluster into a few buckets:

Rank risks by likelihood × impact. This becomes your hardening roadmap.

Avoid perfection. Choose a target that matches current stakes—e.g., “business hours availability,” “99% success for core workflows,” or “restore within 1 hour.” As usage and dependency grow, raise the bar deliberately rather than reacting in a panic.

“Hardening for production” often fails for a simple reason: nobody can say who is responsible for the system end-to-end, and nobody can say what “done” means.

Before you add rate limits, load tests, or a new logging stack, lock in two basics: ownership and scope. They turn an open-ended engineering project into a manageable set of commitments.

Write down who owns the system end-to-end—not just the code. The owner is accountable for availability, data quality, releases, and user impact. That doesn’t mean they do everything; it means they make decisions, coordinate work, and ensure someone is on point when things go wrong.

If ownership is shared, still name a primary: one person/team who can say “yes/no” and keep priorities consistent.

Identify primary user journeys and critical paths. These are the flows where failure creates real harm: signup/login, checkout, sending a message, importing data, generating a report, etc.

Once you have critical paths, you can harden selectively:

Document what’s in scope now vs. later to avoid endless hardening. Production readiness isn’t “perfect software”; it’s “safe enough for this audience, with known limits.” Be explicit about what you’re not supporting yet (regions, browsers, peak traffic, integrations).

Create a lightweight runbook skeleton: how to deploy, rollback, debug. Keep it short and usable at 2 a.m.—a checklist, key dashboards, common failure modes, and who to contact. You can evolve it over time, but you can’t improvise it during your first incident.

Reliability isn’t about making failures impossible—it’s about making behavior predictable when things go wrong or get busy. Prototypes often “work on my machine” because traffic is low, inputs are friendly, and no one is hammering the same endpoint at the same time.

Start with boring, high-leverage defenses:

When the system can’t do the full job, it should still do the safest job. That can mean serving a cached value, disabling a non-critical feature, or returning a “try again” response with a request ID. Prefer graceful degradation over silent partial writes or confusing generic errors.

Under load, duplicate requests and overlapping jobs happen (double-clicks, network retries, queue redelivery). Design for it:

Reliability includes “don’t corrupt data.” Use transactions for multi-step writes, add constraints (unique keys, foreign keys), and practice migration discipline (backwards-compatible changes, tested rollouts).

Set limits on CPU, memory, connection pools, queue sizes, and request payloads. Without limits, one noisy tenant—or one bad query—can starve everything else.

Security hardening doesn’t mean turning your prototype into a fortress. It means meeting a minimum standard where a normal mistake—an exposed link, a leaked token, a curious user—doesn’t become a customer-impacting incident.

If you have “one environment,” you have one blast radius. Create separate dev/staging/prod setups with minimal shared secrets. Staging should be close enough to production to reveal problems, but it should not reuse production credentials or sensitive data.

Many prototypes stop at “log in works.” Production needs least privilege:

Move API keys, database passwords, and signing secrets into a secrets manager or secure environment variables. Then ensure they can’t leak:

You’ll get the most value by addressing a few common failure modes:

Decide who owns updates and how often you patch dependencies and base images. A simple plan (weekly check + monthly upgrades, urgent fixes within 24–72 hours) beats “we’ll do it later.”

Testing is what turns “it worked on my machine” into “it keeps working for customers.” The goal isn’t perfect coverage—it’s confidence in the behaviors that would be most expensive to break: billing, data integrity, permissions, key workflows, and anything that’s hard to debug once deployed.

A practical pyramid usually looks like this:

If your app is mostly API + database, lean heavier on integration tests. If it’s UI-heavy, keep a small set of E2E flows that mirror how users actually succeed (and fail).

When a bug costs time, money, or trust, add a regression test immediately. Prioritize behaviors like “a customer can’t check out,” “a job double-charges,” or “an update corrupts records.” This creates a growing safety net around the highest-risk areas instead of spraying tests everywhere.

Integration tests should be deterministic. Use fixtures and seeded data so test runs don’t depend on whatever happens to be in a developer’s local database. Reset state between tests, and keep test data small but representative.

You don’t need a full load-testing program yet, but you should have quick performance checks for key endpoints and background jobs. A simple threshold-based smoke test (e.g., p95 response time under X ms with small concurrency) catches obvious regressions early.

Every change should run automated gates:

If tests aren’t run automatically, they’re optional—and production will eventually prove that.

When a prototype breaks, you can usually “just try it again.” In production, that guesswork turns into downtime, churn, and long nights. Observability is how you shorten the time between “something feels off” and “here’s exactly what changed, where, and who is impacted.”

Log what matters, not everything. You want enough context to reproduce a problem without dumping sensitive data.

A good rule: every error log should make it obvious what failed and what to check next.

Metrics give you a live pulse check. At minimum, track the golden signals:

These metrics help you tell the difference between “more users” and “something is wrong.”

If one user action triggers multiple services, queues, or third-party calls, tracing turns a mystery into a timeline. Even basic distributed tracing can show where time is spent and which dependency is failing.

Alert spam trains people to ignore alerts. Define:

Build a simple dashboard that instantly answers: Is it down? Is it slow? Why? If it can’t answer those, it’s decoration—not operations.

Hardening isn’t only about code quality—it’s also about how you change the system once people rely on it. Prototypes tolerate “push to main and hope.” Production doesn’t. Release and operations practices turn shipping into a routine activity instead of a high-stakes event.

Make builds and deployments repeatable, scripted, and boring. A simple CI/CD pipeline should: run checks, build the artifact the same way every time, deploy to a known environment, and record exactly what changed.

The win is consistency: you can reproduce a release, compare two versions, and avoid “works on my machine” surprises.

Feature flags let you separate deploy (getting code to production) from release (turning it on for users). That means you can ship small changes frequently, enable them gradually, and shut them off quickly if something misbehaves.

Keep flags disciplined: name them clearly, set owners, and remove them when the experiment is done. Permanent “mystery flags” become their own operational risk.

A rollback strategy is only real if you’ve tested it. Decide what “rollback” means for your system:

Then rehearse in a safe environment. Time how long it takes and document the exact steps. If rollback requires an expert who’s on vacation, it’s not a strategy.

If you’re using a platform that already supports safe reversal, take advantage of it. For example, Koder.ai’s snapshots and rollback workflow can make “stop the bleeding” a first-class, repeatable action while you still keep iteration fast.

Once other systems or customers depend on your interfaces, changes need guardrails.

For APIs: introduce versioning (even a simple /v1) and publish a changelog so consumers know what’s different and when.

For data/schema changes: treat them as first-class releases. Prefer backwards-compatible migrations (add fields before removing old ones), and document them alongside application releases.

“Everything worked yesterday” often breaks because traffic, batch jobs, or customer usage grew.

Set basic protection and expectations:

Done well, release and operations discipline makes shipping feel safe—even when you’re moving fast.

Incidents are inevitable once real users rely on your system. The difference between “a bad day” and “a business-threatening day” is whether you’ve decided—beforehand—who does what, how you communicate, and how you learn.

Keep this as a short doc everyone can find (pin it in Slack, link it in your README, or put it in /runbooks). A practical checklist usually covers:

Write postmortems that focus on fixes, not fault. Good postmortems produce concrete follow-ups: missing alert → add an alert; unclear ownership → assign an on-call; risky deploy → add a canary step. Keep the tone factual and make it easy to contribute.

Track repeats explicitly: the same timeout every week is not “bad luck,” it’s a backlog item. Maintain a recurring-issues list and convert the top offenders into planned work with owners and deadlines.

Define SLAs/SLOs only when you’re ready to measure and maintain them. If you don’t yet have consistent monitoring and someone accountable for response, start with internal targets and basic alerting first, then formalize promises later.

You don’t need to harden everything at once. You need to harden the parts that can hurt users, money, or your reputation—and keep the rest flexible so you can continue learning.

If any of these are in the user journey, treat them as “production paths” and harden them before expanding access:

Keep these lighter while you’re still finding product–market fit:

Try 1–2 weeks focused on the critical path only. Exit criteria should be concrete:

To avoid swinging between chaos and over-engineering, alternate:

If you want a one-page version of this, turn the bullets above into a checklist and review it at every launch or access expansion.

Vibe coding optimizes for speed and learning: prove an idea, validate a workflow, and discover requirements.

Production hardening optimizes for predictability and safety: handle messy inputs, failures, load, and long-term maintainability.

A useful rule: vibe coding answers “Should we build this?”; hardening answers “Can we trust this every day?”

Harden too early when you’re still changing direction weekly and you’re spending more time on architecture than on validating value.

Practical signs you’re too early:

You’ve waited too long when reliability issues are now customer-facing or business-blocking.

Common signals:

The “thin waist” is the small set of core paths that everything depends on (the highest blast-radius flows).

Typically include:

Harden these first; keep peripheral features experimental behind flags.

Use stage-appropriate targets tied to current risk, not perfection.

Examples:

Start by writing down failure modes in plain terms (downtime, wrong results, slow responses), then estimate business impact.

A simple approach:

If “wrong results” is possible, prioritize it—silent incorrectness can be worse than downtime.

At minimum, put guardrails on boundaries and dependencies:

These are high-leverage and don’t require perfect architecture.

Meet a minimum bar that prevents common “easy” incidents:

If you process PII/financial data, treat this as non-negotiable.

Focus testing on the most expensive-to-break behaviors:

Automate in CI so tests aren’t optional: lint/typecheck + unit/integration + basic dependency scanning.

Make it easy to answer: “Is it down? Is it slow? Why?”

Practical starters:

This turns incidents into routines instead of emergencies.