May 25, 2025·8 min

Why Abstractions Beat Syntax in Large, Long-Lived Codebases

Learn why clear abstractions, naming, and boundaries reduce risk and speed up changes in big codebases—often more than syntax choices do.

Learn why clear abstractions, naming, and boundaries reduce risk and speed up changes in big codebases—often more than syntax choices do.

When people argue about programming languages, they often argue about syntax: the words and symbols you type to express an idea. Syntax covers things like curly braces vs. indentation, how you declare variables, or whether you write map() or a for loop. It affects readability and developer comfort—but mostly at the “sentence structure” level.

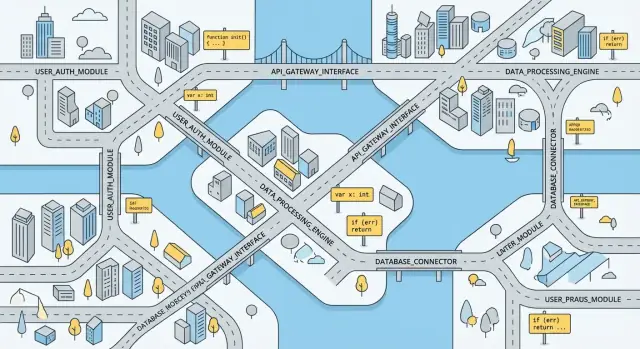

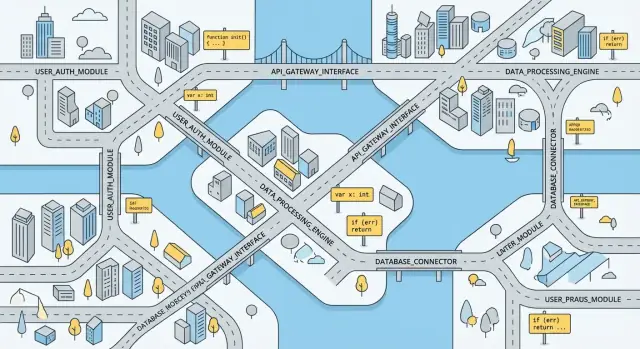

Abstraction is different. It’s the “story” your code tells: the concepts you choose, how you group responsibilities, and the boundaries that keep changes from rippling everywhere. Abstractions show up as modules, functions, classes, interfaces, services, and even simple conventions like “all money is stored in cents.”

In a small project, you can keep most of the system in your head. In a large, long-lived codebase, you can’t. New teammates join, requirements change, and features get added in surprising places. At that point, success depends less on whether the language is “nice to write” and more on whether the code has clear concepts and stable seams.

Languages still matter: some make certain abstractions easier to express or harder to misuse. The point isn’t “syntax is irrelevant.” It’s that syntax is rarely the bottleneck once a system becomes big.

You’ll learn how to spot strong vs. weak abstractions, why boundaries and naming do heavy lifting, common traps (like leaky abstractions), and practical ways to refactor toward code that’s easier to change without fear.

A small project can survive on “nice syntax” because the cost of a misstep stays local. In a large, long-lived codebase, every decision gets multiplied: more files, more contributors, more release trains, more customer requests, and more integration points that can break.

Most engineering time isn’t spent writing brand-new code. It’s spent:

When that’s your daily reality, you care less about whether a language lets you express a loop elegantly and more about whether the codebase has clear seams—places where you can make changes without needing to understand everything.

In a large team, “local” choices rarely stay local. If one module uses a different error style, naming scheme, or dependency direction, it creates extra mental load for everyone who touches it later. Multiply that by hundreds of modules and years of turnover, and the codebase becomes expensive to navigate.

Abstractions (good boundaries, stable interfaces, consistent naming) are coordination tools. They let different people work in parallel with fewer surprises.

Imagine adding “trial expiration notifications.” Sounds simple—until you trace the path:

If those areas are connected through clear interfaces (e.g., a billing API that exposes “trial status” without exposing its tables), you can implement the change with contained edits. If everything reaches into everything else, the feature becomes a risky cross-cutting surgery.

At scale, priorities shift from clever expressions to safe, predictable change.

Good abstractions are less about hiding “complexity” and more about exposing intent. When you read a well-designed module, you should learn what the system is doing before you’re forced to learn how it does it.

A good abstraction turns a pile of steps into a single, meaningful idea: Invoice.send() is easier to reason about than “format PDF → pick email template → attach file → retry on failure.” The details still exist, but they live behind a boundary where they can change without dragging the rest of the code along.

Large codebases become hard when every change requires reading ten files “just to be safe.” Abstractions shrink the required reading. If the calling code depends on a clear interface—“charge this customer,” “fetch user profile,” “calculate tax”—you can change the implementation with confidence you’re not accidentally altering unrelated behavior.

Requirements don’t just add features; they change assumptions. Good abstractions create a small number of places to update those assumptions.

For example, if payment retries, fraud checks, or currency conversion rules change, you want one payment boundary to update—rather than fixing scattered call sites across the app.

Teams move faster when everyone shares the same “handles” for the system. Consistent abstractions become mental shortcuts:

Repository for reads and writes”HttpClient”Flags”These shortcuts reduce debate in code review and make onboarding easier, because patterns repeat predictably instead of being rediscovered in every folder.

It’s tempting to believe that switching languages, adopting a new framework, or enforcing a stricter style guide will “fix” a messy system. But changing syntax rarely changes the underlying design problems. If dependencies are tangled, responsibilities are unclear, and modules can’t be changed independently, prettier syntax just gives you cleaner-looking knots.

Two teams can build the same feature set in different languages and still end up with the same pain: business rules scattered across controllers, direct database access from everywhere, and “utility” modules that slowly become a dumping ground.

That’s because structure is mostly independent of syntax. You can write:

When a codebase is hard to change, the root cause is usually boundaries: unclear interfaces, mixed concerns, and hidden coupling. Syntax debates can become a trap—teams spend hours arguing about braces, decorators, or naming style while the real work (separating responsibilities and defining stable interfaces) is postponed.

Syntax isn’t irrelevant; it just matters in narrower, more tactical ways.

Readability. Clear, consistent syntax helps humans scan code quickly. This is especially valuable in modules that many people touch—core domain logic, shared libraries, and integration points.

Correctness in hot spots. Some syntax choices reduce bugs: avoiding ambiguous precedence, preferring explicit types where it prevents misuse, or using language constructs that make illegal states unrepresentable.

Local expressiveness. In performance-critical or security-sensitive areas, details matter: how errors are handled, how concurrency is expressed, or how resources are acquired and released.

The takeaway: use syntax rules to reduce friction and prevent common mistakes, but don’t expect them to cure design debt. If the codebase is fighting you, focus on shaping better abstractions and boundaries first—then let style serve that structure.

Big codebases don’t usually fail because a team chose the “wrong” syntax. They fail because everything can touch everything else. When boundaries are blurry, small changes ripple across the system, reviews get noisy, and “quick fixes” become permanent coupling.

Healthy systems are made of modules with clear responsibilities. Unhealthy systems accumulate “god objects” (or god modules) that know too much and do too much: validation, persistence, business rules, caching, formatting, and orchestration all in one place.

A good boundary lets you answer: What does this module own? What does it explicitly not own? If you can’t say that in a sentence, it’s probably too broad.

Boundaries become real when they’re backed by stable interfaces: inputs, outputs, and behavioral guarantees. Treat these as contracts. When two parts of the system talk, they should do so through a small surface area that can be tested and versioned.

This is also how teams scale: different people can work on different modules without coordinating every line, because the contract is what matters.

Layering (UI → domain → data) works when details don’t leak upward.

When details leak, you get “just pass the database entity up” shortcuts that lock you into today’s storage choices.

A simple rule keeps boundaries intact: dependencies should point inward toward the domain. Avoid designs where everything depends on everything; that’s where change becomes risky.

If you’re unsure where to start, draw a dependency graph for one feature. The most painful edge is usually the first boundary worth fixing.

Names are the first abstraction people interact with. Before a reader understands a type hierarchy, a module boundary, or a data flow, they’re parsing identifiers and building a mental model from them. When naming is clear, that model forms quickly; when naming is vague or “cute,” every line becomes a puzzle.

A good name answers: what is this for? not how is it implemented? Compare:

process() vs applyDiscountRules()data vs activeSubscriptionshandler vs invoiceEmailSender“Clever” names age badly because they rely on context that disappears: inside jokes, abbreviations, or wordplay. Intention-revealing names travel well across teams, time zones, and new hires.

Large codebases live or die by shared language. If your business calls something a “policy,” don’t name it contract in code—those are different concepts to domain experts, even if the database table looks similar.

Aligning vocabulary with the domain has two benefits:

If your domain language is messy, that’s a signal to collaborate with product/ops and agree on a glossary. Code can then reinforce that agreement.

Naming conventions are less about style and more about predictability. When readers can infer purpose from shape, they move faster and break less.

Examples of conventions that pay off:

Repository, Validator, Mapper, Service only when they match a real responsibility.is, has, can) and event names in past tense (PaymentCaptured).users is a collection, user is a single item.The goal isn’t strict policing; it’s lowering the cost of understanding. In long-lived systems, that’s a compounding advantage.

A large codebase is read far more often than it’s written. When each team (or each developer) solves the same kind of problem in a different style, every new file becomes a small puzzle. That inconsistency forces readers to re-learn the “local rules” of each area—how errors are handled here, how data is validated there, what the preferred way is to structure a service somewhere else.

Consistency doesn’t mean boring code. It means predictable code. Predictability reduces cognitive load, shortens review cycles, and makes changes safer because people can rely on familiar patterns instead of re-deriving intent from clever constructs.

Clever solutions often optimize for the author’s short-term satisfaction: a neat trick, a compact abstraction, a bespoke mini-framework. But in long-lived systems, the cost shows up later:

The result is a codebase that feels larger than it is.

When a team uses shared patterns for recurring problem types—API endpoints, database access, background jobs, retries, validation, logging—each new instance is faster to understand. Reviewers can focus on business logic rather than debating structure.

Keep the set small and intentional: a few approved patterns per problem type, rather than endless “options.” If there are five ways to do pagination, you effectively have no standard.

Standards work best when they’re concrete. A short internal page that shows:

…will do more than a long style guide. This also creates a neutral reference point in code reviews: you’re not arguing preferences, you’re applying a team decision.

If you need a place to start, pick one high-churn area (the part of the system that changes most often), agree on a pattern, and refactor toward it over time. Consistency is rarely achieved by decree; it’s achieved by steady, repeated alignment.

A good abstraction doesn’t just make code easier to read—it makes code easier to change. The best sign you’ve found the right boundary is that a new feature or bug fix only touches a small area, and the rest of the system stays confidently untouched.

When an abstraction is real, you can describe it as a contract: given these inputs, you get these outputs, with a few clear rules. Your tests should mostly live at that contract level.

For example, if you have a PaymentGateway interface, tests should assert what happens when a payment succeeds, fails, or times out—not which helper methods were called or what internal retry loop you used. That way, you can improve performance, swap providers, or refactor internals without rewriting half your test suite.

If you can’t easily list the contract, it’s a hint the abstraction is fuzzy. Tighten it by answering:

Once those are clear, test cases almost write themselves: one or two for each rule, plus a few edge cases.

Tests become fragile when they lock in implementation choices instead of behavior. Common smells include:

If a refactor forces you to rewrite many tests without changing user-visible behavior, that’s usually a testing strategy problem—not a refactor problem. Focus on observable outcomes at boundaries, and you’ll get the real prize: safe change at speed.

Good abstractions reduce what you need to think about. Bad ones do the opposite: they look clean until real requirements hit, and then they demand insider knowledge or extra ceremony.

A leaky abstraction forces callers to know internal details to use it correctly. The tell is when usage requires comments like “you must call X before Y” or “this only works if the connection is already warmed up.” At that point, the abstraction isn’t protecting you from complexity—it’s relocating it.

Typical leak patterns:

If callers routinely add the same guard code, retries, or ordering rules, that logic belongs inside the abstraction.

Too many layers can make straightforward behavior hard to trace and slow debugging. A wrapper around a wrapper around a helper can turn a one-line decision into a scavenger hunt. This often happens when abstractions are created “just in case,” before there’s a clear, repeated need.

You’re likely in trouble if you see frequent workarounds, repeated special cases, or a growing set of escape hatches (flags, bypass methods, “advanced” parameters). Those are signals that the abstraction’s shape doesn’t match how the system is actually used.

Prefer a small, opinionated interface that covers the common path well. Add capabilities only when you can point to multiple real callers that need them—and when you can explain the new behavior without referencing internals.

When you must expose an escape hatch, make it explicit and rare, not the default path.

Refactoring toward better abstractions is less about “cleaning up” and more about changing the shape of work. The goal is to make future changes cheaper: fewer files to edit, fewer dependencies to understand, fewer places where a small tweak can break something unrelated.

Large rewrites promise clarity but often reset hard-won knowledge embedded in the system: edge cases, performance quirks, and operational behavior. Small, continuous refactors let you pay down technical debt while shipping.

A practical approach is to attach refactoring to real feature work: every time you touch an area, make it slightly easier to touch next time. Over months, this compounds.

Before you move logic around, create a seam: an interface, wrapper, adapter, or façade that gives you a stable place to plug changes in. Seams let you redirect behavior without rewriting everything at once.

For example, wrap direct database calls behind a repository-like interface. Then you can change queries, caching, or even the storage technology while the rest of the code continues to talk to the same boundary.

This is also a useful mental model when you’re building quickly with AI-assisted tools: the fastest path is still to establish the boundary first, then iterate behind it.

A good abstraction reduces how much of the codebase must be modified for a typical change. Track this informally:

If changes consistently require fewer touchpoints, your abstractions are improving.

When changing a major abstraction, migrate in slices. Use parallel paths (old + new) behind a seam, then gradually route more traffic or use cases to the new path. Incremental migrations reduce risk, avoid downtime, and make rollbacks realistic when surprises appear.

Practically, teams benefit from tooling that makes rollback cheap. Platforms like Koder.ai bake this into the workflow with snapshots and rollback, so you can iterate on architecture changes—especially boundary refactors—without betting the entire release on a single irreversible migration.

When you review code in a long-lived codebase, the goal isn’t to find the “prettiest” syntax. It’s to reduce future cost: fewer surprises, easier changes, safer releases. A practical review focuses on boundaries, names, coupling, and tests—then lets formatting be handled by tools.

Ask what this change depends on—and what will now depend on it.

Look for code that belongs together and code that’s tangled.

Treat naming as part of the abstraction.

A simple question guides many decisions: does this change increase or decrease future flexibility?

Enforce mechanical style automatically (formatters, linters). Save discussion time for design questions: boundaries, naming, and coupling.

Big, long-lived codebases don’t usually fail because a language feature is missing. They fail when people can’t tell where a change should happen, what it might break, and how to make it safely. That’s an abstraction problem.

Prioritize clear boundaries and intent over language debates. A well-drawn module boundary—with a small public surface and a clear contract—beats “clean” syntax inside a tangled dependency graph.

When you feel a debate turning into “tabs vs spaces” or “language X vs language Y,” redirect it to questions like:

Create a shared glossary for domain concepts and architectural terms. If two people use different words for the same idea (or the same word for different ideas), your abstractions are already leaking.

Keep a small set of patterns that everyone recognizes (e.g., “service + interface,” “repository,” “adapter,” “command”). Fewer patterns, used consistently, make code easier to navigate than a dozen clever designs.

Put tests at module boundaries, not only inside modules. Boundary tests let you refactor internals aggressively while keeping behavior stable for callers—this is how abstractions stay “honest” over time.

If you’re building new systems quickly—especially with vibe-coding workflows—treat boundaries as the first artifact you “lock in.” For example, in Koder.ai you can start in planning mode to sketch the contracts (React UI → Go services → PostgreSQL data), then generate and iterate on implementation behind those contracts, exporting the source code whenever you need full ownership.

Pick one high-churn area and:

Turn these moves into norms—refactor as you go, keep public surfaces small, and treat naming as part of the interface.

Syntax is the surface form: keywords, punctuation, and layout (braces vs indentation, map() vs loops). Abstraction is the conceptual structure: modules, boundaries, contracts, and naming that tell readers what the system does and where changes should happen.

In large codebases, abstraction usually dominates because most work is reading and changing code safely, not writing fresh code.

Because scale changes the cost model: decisions get multiplied across many files, teams, and years. A small syntax preference stays local; a weak boundary creates ripple effects everywhere.

In practice, teams spend more time finding, understanding, and safely modifying behavior than writing new lines, so clear seams and contracts matter more than “nice to write” constructs.

Look for places where you can change one behavior without needing to understand unrelated parts. Strong abstractions typically have:

A seam is a stable boundary that lets you change implementation without changing callers—often an interface, adapter, façade, or wrapper.

Add seams when you need to refactor or migrate safely: first create a stable API (even if it delegates to the old code), then move logic behind it incrementally.

A leaky abstraction forces callers to know hidden rules to use it correctly (ordering constraints, lifecycle quirks, magic defaults).

Common fixes:

Over-engineering shows up as layers that add ceremony without reducing cognitive load—wrappers around wrappers where simple behavior becomes hard to trace.

A practical rule: introduce a new layer only when you have multiple real callers with the same need, and you can describe the contract without referencing internals. Prefer a small, opinionated interface over a “do everything” one.

Naming is the first interface people read. Intention-revealing names reduce the amount of code someone must inspect to understand behavior.

Good practices:

applyDiscountRules over process)Boundaries are real when they come with contracts: clear inputs/outputs, guaranteed behaviors, and defined error handling. That’s what lets teams work independently.

If the UI knows database tables, or domain code depends on HTTP concepts, details are leaking across layers. Aim for dependencies to point inward toward domain concepts, with adapters at the edges.

Test behavior at the contract level: given inputs, assert outputs, errors, and side effects. Avoid tests that lock in internal steps.

Brittle test smells include:

Boundary-focused tests let you refactor internals without rewriting half the suite.

Focus reviews on future change cost, not aesthetics. Useful questions:

Automate formatting with linters/formatters so review time goes to design and coupling.

Repository, booleans with is/has/can, events in past tense)