Aug 09, 2025·8 min

Why Angular Embraced Structure and Opinions for Large Apps

Angular favors structure and opinions to help large teams build maintainable apps: consistent patterns, tooling, TypeScript, DI, and scalable architecture.

Angular favors structure and opinions to help large teams build maintainable apps: consistent patterns, tooling, TypeScript, DI, and scalable architecture.

Angular is often described as opinionated. In framework terms, that means it doesn’t just provide building blocks—it also recommends (and sometimes enforces) specific ways to assemble them. You’re guided toward certain file layouts, patterns, tooling, and conventions so that two Angular projects tend to “feel” similar, even when they’re built by different teams.

Angular’s opinions show up in how you create components, how you organize features, how dependency injection is used by default, and how routing is typically configured. Instead of asking you to choose among many competing approaches, Angular narrows the set of recommended options.

That trade-off is deliberate:

Small apps can tolerate experimentation: different coding styles, multiple libraries for the same job, or ad-hoc patterns that evolve over time. Large Angular applications—especially those maintained for years—pay a high price for that flexibility. In big codebases, the hardest problems are often coordination problems: onboarding new developers, reviewing pull requests quickly, refactoring safely, and keeping dozens of features working together.

Angular’s structure aims to make those activities predictable. When patterns are consistent, teams can move between features confidently and spend more effort on product work instead of re-learning “how this part was built.”

The rest of the article breaks down where Angular’s structure comes from—its architecture choices (components, modules/standalone, DI, routing), its tooling (Angular CLI), and how these opinions support teamwork and long-term maintenance at scale.

Small apps can survive a lot of “whatever works” decisions. Large Angular applications usually can’t. Once multiple teams touch the same codebase, tiny inconsistencies multiply into real costs: duplicated utilities, slightly different folder structures, competing state patterns, and three ways to handle the same API error.

As a team grows, people naturally copy what they see nearby. If the codebase doesn’t clearly signal preferred patterns, the result is code drift—new features follow the last developer’s habits, not a shared approach.

Conventions reduce the number of decisions developers must make per feature. That shortens onboarding time (new hires learn “the Angular way” inside your repo) and reduces review friction (fewer comments like “this doesn’t match our pattern”).

Enterprise frontends are rarely “done.” They live through maintenance cycles, refactors, redesigns, and constant feature churn. In that environment, structure is less about aesthetics and more about survival:

Big apps inevitably share cross-cutting needs: routing, permissions, internationalization, testing, and integration with backends. If each feature team solves these differently, you end up debugging interactions instead of building product.

Angular’s opinions—around modules/standalone boundaries, dependency injection, routing, and tooling—aim to make these concerns consistent by default. The payoff is straightforward: fewer special cases, less rework, and smoother collaboration over years.

Angular’s core unit is the component: a self-contained piece of UI with clear boundaries. When a product grows, those boundaries keep pages from turning into giant files where “everything affects everything.” Components make it obvious where a feature lives, what it owns (template, styles, behavior), and how it can be reused.

A component is split into a template (HTML that describes what users see) and a class (TypeScript that holds state and behavior). That separation encourages a clean division between presentation and logic:

// user-card.component.ts

@Component({ selector: 'app-user-card', templateUrl: './user-card.component.html' })

export class UserCardComponent {

@Input() user!: { name: string };

@Output() selected = new EventEmitter<void>();

onSelect() { this.selected.emit(); }

}

<!-- user-card.component.html -->

<h3>{{ user.name }}</h3>

<button (click)="onSelect()">Select</button>

Angular promotes a straightforward contract between components:

@Input() passes data down from a parent to a child.@Output() sends events up from a child to a parent.This convention makes data flow easier to reason about, especially in large Angular applications where multiple teams touch the same screens. When you open a component, you can quickly identify:

Because components follow consistent patterns (selectors, file naming, decorators, bindings), developers can recognize structure at a glance. That shared “shape” reduces handover friction, speeds up reviews, and makes refactoring safer—without requiring everyone to memorize custom rules for each feature.

As an app grows, the hardest problem often isn’t writing new features—it’s finding the right place to put them and understanding who “owns” what. Angular leans into structure so teams can keep moving without constantly renegotiating conventions.

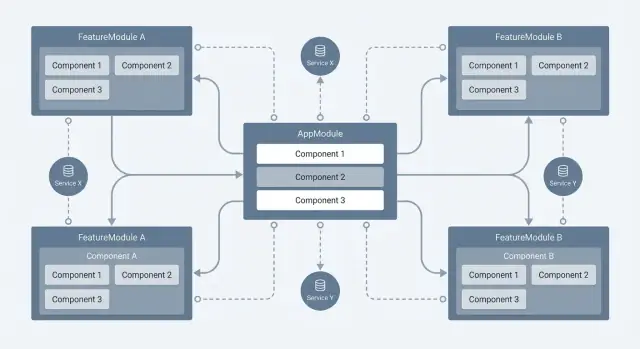

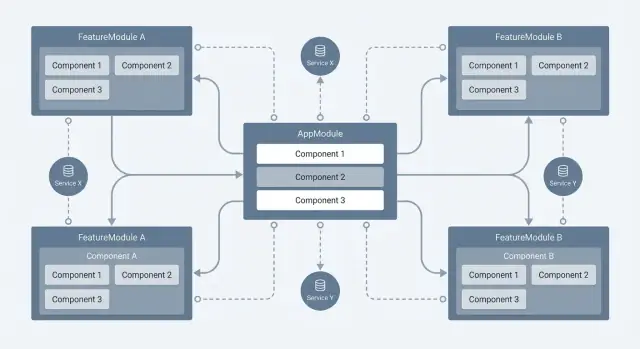

Historically, NgModules grouped related components, directives, and services into a feature boundary (e.g., OrdersModule). Modern Angular also supports standalone components, which reduce the need for NgModules while still encouraging clear “feature slices” through routing and folder structure.

Either way, the goal is the same: make features discoverable and keep dependencies intentional.

A common scalable pattern is organizing by feature rather than by type:

features/orders/ (pages, components, services specific to orders)features/billing/features/admin/When each feature folder contains most of what it needs, a developer can open one directory and quickly understand how that area works. It also maps neatly to team ownership: “the Orders team owns everything under features/orders.”

Angular teams often split reusable code into:

A common mistake is turning shared/ into a dumping ground. If “shared” imports everything and everyone imports “shared,” dependencies become tangled and build times grow. A better approach is to keep shared pieces small, focused, and dependency-light.

Between module/standalone boundaries, dependency injection defaults, and routing-based feature entry points, Angular naturally pushes teams toward a predictable folder layout and a clearer dependency graph—key ingredients for large Angular applications that stay maintainable.

Angular’s dependency injection (DI) isn’t an optional add-on—it’s the expected way to wire your app together. Instead of components creating their own helpers (new ApiService()), they ask for what they need, and Angular provides the correct instance. This encourages a clean split between UI (components) and behavior (services).

DI makes three big things easier in large codebases:

Because dependencies are declared in constructors, you can quickly see what a class relies on—useful when refactoring or reviewing unfamiliar code.

Where you provide a service determines its lifetime. A service provided in root (for example, providedIn: 'root') behaves like an app-wide singleton—great for cross-cutting concerns, but risky if it quietly accumulates state.

Feature-level providers create instances scoped to that feature (or route), which can prevent accidental shared state. The key is to be intentional: stateful services should have clear ownership, and you should avoid “mystery globals” that store data simply because they happen to be singletons.

Typical DI-friendly services include API/data access (wrapping HTTP calls), auth/session (tokens, user state), and logging/telemetry (centralized error reporting). DI keeps these concerns consistent across the app without tangling them into components.

Angular treats routing as a first-class part of application design, not an afterthought. That opinion matters once an app grows beyond a few screens: navigation becomes a shared contract that every team and feature relies on. With a central Router, consistent URL patterns, and declarative route configuration, it’s easier to reason about “where you are” and what should happen when a user moves around.

Lazy loading lets Angular load feature code only when the user actually navigates to it. The immediate win is performance: smaller initial bundles, faster startup, and fewer resources downloaded for users who never visit certain areas.

The longer-term win is organizational. When each major feature has its own route entry point, you can split work across teams with clearer ownership. A team can evolve its feature area (and its internal routes) without constantly touching global app wiring—reducing merge conflicts and accidental coupling.

Large apps often need rules around navigation: authentication, authorization, unsaved changes, feature flags, or required context. Angular route guards make these rules explicit at the route level instead of scattered across components.

Resolvers add predictability by fetching required data before activating a route. That helps keep screens from rendering half-ready states, and it makes “what data is required for this page?” part of the routing contract—useful for maintenance and onboarding.

A scaling-friendly approach is feature-based routing:

/admin, /billing, /settings).This structure encourages consistent URLs, clear boundaries, and incremental loading—exactly the kind of structure that makes large Angular applications easier to evolve over time.

Angular’s choice to make TypeScript the default isn’t just a syntax preference—it’s an opinion about how large apps should evolve. When dozens of people touch the same codebase over years, “works right now” isn’t enough. TypeScript pushes you to describe what your code expects, so changes are easier to make without breaking unrelated features.

By default, Angular projects are set up so components, services, and APIs have explicit shapes. That nudges teams toward:

This structure makes the codebase feel less like a collection of scripts and more like an application with clear boundaries.

TypeScript’s real value shows up in editor support. With types in place, your IDE can offer reliable autocomplete, detect mistakes before runtime, and perform safer refactors.

For example, if you rename a field in a shared model, tooling can find every reference across templates, components, and services—reducing the “search and hope” approach that often leads to missed edge cases.

Large apps change continuously: new requirements, API revisions, reorganized features, and performance work. Types act like guardrails during these shifts. When something no longer matches the expected contract, you find out during development or CI—not after a user hits a rare path in production.

Types won’t guarantee correct logic, good UX, or perfect data validation. But they dramatically improve team communication: the code itself documents intent. New teammates can understand what a service returns, what a component needs, and what “valid data” looks like—without reading every implementation detail.

Angular’s opinions aren’t only in framework APIs—they’re also embedded in how teams create, build, and maintain projects. The Angular CLI is a big reason large Angular applications tend to feel consistent even across different companies.

From the first command, the CLI sets a shared baseline: project structure, TypeScript configuration, and recommended defaults. It also provides a single, predictable interface for the tasks teams run every day:

This standardization matters because build pipelines are often where teams diverge and accumulate “special cases.” With Angular CLI, many of those choices are made once and shared broadly.

Large teams need repeatability: the same app should behave similarly on every laptop and in CI. The CLI encourages a single configuration source (for example, build options and environment-specific settings) rather than a collection of ad-hoc scripts.

That consistency reduces time lost to “works on my machine” problems—where local scripts, mismatched Node versions, or unshared build flags create hard-to-reproduce bugs.

Angular CLI schematics help teams create components, services, modules, and other building blocks in a consistent style. Instead of everyone hand-rolling boilerplate, generation nudges developers into the same naming, file layout, and wiring patterns—exactly the kind of small discipline that pays off when the codebase grows.

If you want a similar “standardize the workflow” effect earlier in the lifecycle—especially for quick proof-of-concepts—platforms like Koder.ai can help teams generate a working app from chat, then export source code and iterate with clearer conventions once the direction is validated. It’s not an Angular replacement (its default stack targets React + Go + PostgreSQL and Flutter), but the underlying idea is the same: reduce setup friction so teams spend more time on product decisions and less on scaffolding.

Angular’s opinionated testing story is one reason big teams can keep quality high without reinventing the process for every feature. The framework doesn’t just allow testing—it nudges you toward repeatable patterns that scale.

Most Angular unit and component tests start with TestBed, which creates a small, configurable Angular “mini app” for the test. That means your test setup mirrors real dependency injection and template compilation, instead of ad-hoc wiring.

Component tests typically use a ComponentFixture, giving a consistent way to render templates, trigger change detection, and assert on the DOM.

Because Angular relies heavily on dependency injection, mocking is straightforward: override providers with fakes, stubs, or spies. Common helpers like HttpClientTestingModule (to intercept HTTP calls) and RouterTestingModule (to fake navigation) encourage the same setup across teams.

When the framework encourages the same module imports, provider overrides, and fixture flow, test code becomes familiar. New teammates can read tests like documentation, and shared utilities (test builders, common mocks) work across the app.

Unit tests work best for pure services and business rules: fast, focused, and easy to run on every change.

Integration tests are ideal for “a component + its template + a few real dependencies” to catch wiring issues (bindings, forms behavior, routing params) without the cost of full end-to-end runs.

E2E tests should be fewer and reserved for critical user journeys—authentication, checkout, core navigation—where you want confidence the system works as a whole.

Test services as the primary owners of logic (validation, calculations, data mapping). Keep components thinner: test that they call the right service methods, react to outputs, and render states correctly. If a component test needs heavy mocking, it’s a signal the logic may belong in a service instead.

Angular’s opinions show up clearly in two everyday areas: forms and network calls. When teams align on built-in patterns, code reviews get faster, bugs get easier to reproduce, and new features don’t reinvent the same plumbing.

Angular supports template-driven and reactive forms. Template-driven forms feel straightforward for simple screens because the template holds most of the logic. Reactive forms push structure into TypeScript using FormControl and FormGroup, which tends to scale better when forms get large, dynamic, or heavily validated.

Whichever approach you pick, Angular encourages consistent building blocks:

touched)aria-describedby for error text, keeping focus behavior consistent)Teams often standardize on a shared “form field” component that renders labels, hints, and error messages the same way everywhere—reducing one-off UI logic.

Angular’s HttpClient pushes a consistent request model (observables, typed responses, centralized configuration). The scaling win is interceptors, which let you apply cross-cutting behavior globally:

Instead of scattering “if 401 then redirect” across dozens of services, you enforce it once. That consistency reduces duplication, makes behavior predictable, and keeps feature code focused on business logic rather than plumbing.

Angular’s performance story is tightly linked to predictability. Instead of encouraging “do anything anywhere,” it nudges you to think in terms of when the UI should update and why.

Angular updates the view through change detection. In simple terms: when something might have changed (an event, an async callback, an input update), Angular checks component templates and refreshes the DOM where needed.

For large apps, the key mental model is: updates should be intentional and localized. The more your component tree can avoid unnecessary checks, the more stable performance becomes as screens get denser.

Angular bakes in patterns that are easy to apply consistently across teams:

ChangeDetectionStrategy.OnPush: tells Angular a component should re-render mainly when its @Input() references change, an event happens inside it, or an observable emits via async.trackBy in *ngFor: prevents Angular from re-creating DOM nodes when a list updates, as long as item identity is stable.These aren’t just “tips”—they’re conventions that prevent accidental regressions when new features get added quickly.

Use OnPush by default for presentational components, and pass data as immutable-ish objects (replace arrays/objects instead of mutating in place).

For lists: always add trackBy, paginate or virtualize when lists grow, and avoid running expensive calculations in templates.

Keep routing boundaries meaningful: if a feature can be opened from navigation, it’s usually a good candidate for lazy loading.

The result is a codebase where performance characteristics stay understandable—even as the app and the team scale.

Angular’s structure pays off when an app is big, long-lived, and maintained by many people—but it’s not free.

First is the learning curve. Concepts like dependency injection, RxJS patterns, and template syntax can take time to internalize, especially for teams coming from simpler setups.

Second is verbosity. Angular favors explicit configuration and clear boundaries, which can mean more files and more “ceremony” for small features.

Third is reduced flexibility. Conventions (and the “Angular way” of doing things) can constrain experimentation. You can still integrate other tools, but you’ll often be adapting them to Angular’s patterns rather than the other way around.

If you’re building a prototype, a marketing site, or a small internal tool with a short lifespan, the overhead may not be worth it. Small teams that ship quickly and iterate heavily sometimes prefer frameworks with fewer built-in rules so they can tailor architecture as they go.

Ask a few practical questions:

You don’t have to “go all in” at once. Many teams start by tightening conventions (linting, folder structure, testing baselines), then modernize incrementally with standalone components and more focused feature boundaries over time.

If you’re migrating, aim for steady improvements rather than a big rewrite—and document your local conventions in one place so “the Angular way” in your repo stays explicit and teachable.

In Angular, “structure” is the set of default patterns the framework and tooling encourage: components with templates, dependency injection, routing configuration, and common project layouts generated by the CLI.

“Opinions” are the recommended ways to use those patterns—so most Angular apps end up organized similarly, which makes large codebases easier to navigate and maintain.

It reduces coordination costs in big teams. With consistent conventions, developers spend less time debating folder structures, state boundaries, and tooling choices.

The main trade-off is flexibility: if your team prefers a very different architecture, you may feel friction when working against Angular’s defaults.

Code drift happens when developers copy nearby code and introduce slightly different patterns over time.

To limit drift:

features/orders/, features/billing/).Angular’s defaults make these habits easier to adopt consistently.

Components give you a consistent unit of UI ownership: template (rendering) + class (state/behavior).

They scale well because boundaries are explicit:

@Input() passes data from parent to child; @Output() emits events from child to parent.

This creates predictable, easy-to-review data flow:

NgModules historically grouped related declarations and providers behind a feature boundary. Standalone components reduce module boilerplate while still supporting clear feature slices (often via routing and folders).

A practical rule:

A common split is:

Avoid the “god shared module” by keeping shared pieces dependency-light and importing only what you need per feature.

Dependency Injection (DI) makes dependencies explicit and replaceable:

Instead of new ApiService(), components request services and Angular provides the right instance.

Provider scope controls lifetime:

providedIn: 'root' is effectively a singleton—great for cross-cutting concerns, risky for hidden mutable state.Be intentional: keep state ownership clear, and avoid “mystery globals” that accumulate data just because they’re singletons.

Lazy loading improves performance and helps team boundaries:

Guards and resolvers keep navigation rules explicit: