Jun 14, 2025·8 min

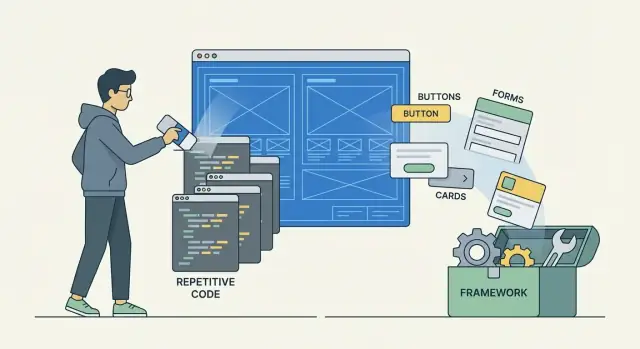

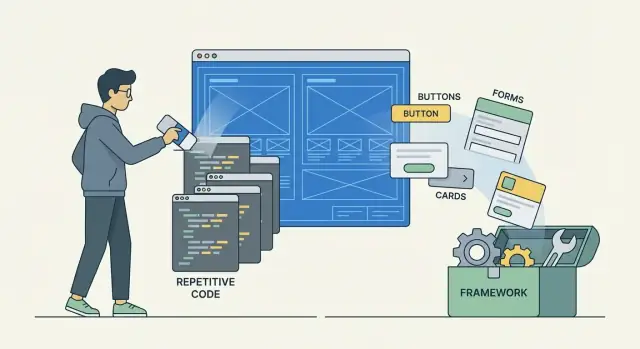

Why Boilerplate Exists and How Frameworks Reduce It

Learn why boilerplate code exists, what problems it solves, and how frameworks cut repetition with conventions, scaffolding, and reusable components.

Learn why boilerplate code exists, what problems it solves, and how frameworks cut repetition with conventions, scaffolding, and reusable components.

Boilerplate code is the repeated “setup” and glue code you end up writing across many projects—even when the product idea changes. It’s the scaffolding that helps an application start, connect pieces together, and behave consistently, but it usually isn’t where your app’s unique value lives.

Think of boilerplate as the standard checklist you keep reusing:

If you’ve built more than one app, you’ve probably copied some of this from an older project or repeated the same steps again.

Most apps share the same baseline needs: users sign in, pages or endpoints need routing, requests can fail, and data needs validation and storage. Even simple projects benefit from guardrails—otherwise you spend time chasing inconsistent behavior (for example, different error responses in different endpoints).

Repetition can be annoying, but boilerplate often provides structure and safety. A consistent way to handle errors, authenticate users, or configure environments can prevent bugs and make a codebase easier for a team to understand.

The issue isn’t that boilerplate exists—it’s when it grows so large that it slows changes, hides the business logic, or invites copy‑paste mistakes.

Imagine building several websites. Each one needs the same header and footer, a contact form with validation, and a standard way to send form submissions to an email or CRM.

Or consider any app that calls an external service: every project needs the same API client setup—base URL, authentication token, retries, and friendly error messages. That repeated scaffolding is boilerplate.

Boilerplate isn’t usually written because developers enjoy repetition. It exists because many applications share the same non-negotiable needs: handling requests, validating input, connecting to data stores, logging what happened, and failing safely when something goes wrong.

When a team finds a “known-good” way to do something—like safely parsing user input or retrying a database connection—it gets reused. That repetition is a form of risk management: the code may be boring, but it’s less likely to break production.

Even small teams benefit from having the same folder layout, naming conventions, and request/response flow across projects. Consistency makes onboarding faster, reviews easier, and bug fixes more straightforward because everyone knows where to look.

Real apps rarely live in isolation. Boilerplate often appears where systems meet: web server + routing, database + migrations, logging + monitoring, background jobs + queues. Each integration needs setup code, configuration, and “wiring” to make the pieces cooperate.

Many projects require baseline protections: validation, authentication hooks, security headers, rate limiting, and sensible error handling. You can’t skip these, so teams reuse templates to avoid missing critical safeguards.

Deadlines push developers toward copying working patterns rather than reinventing them. Boilerplate becomes a shortcut: not the best part of the codebase, but a practical way to move from idea to release. If you’re using project templates, you’re already seeing this in action.

Boilerplate can feel “safe” because it’s familiar and already written. But once it spreads across a codebase, it quietly taxes every future change. The cost isn’t just extra lines—it’s extra decisions, extra places to look, and extra chances for things to drift.

Every repeated pattern increases surface area:

Even small changes—like adding a header, updating an error message, or changing a config value—can turn into a scavenger hunt across many near-identical files.

A boilerplate-heavy project is harder to learn because newcomers can’t easily tell what matters:

When a project has multiple ways to do the same thing, people spend energy memorizing quirks instead of understanding the product.

Duplicated code rarely stays identical for long:

Boilerplate also ages poorly:

A snippet copied from an older project might rely on old defaults. It can run “well enough” until it fails under load, during an upgrade, or in production—when it’s most expensive to debug.

Boilerplate isn’t one big chunk of “extra code.” It usually appears in small, repeated patterns spread across the entire project—especially once an app grows beyond a single page or script.

Most web and API apps repeat the same structure for handling requests:

Even when each file is short, the pattern repeats across many endpoints.

A lot of boilerplate happens before the app does anything useful:

This code is often similar across projects, but still needs to be written and maintained.

These features touch many parts of the codebase, which makes repetition common:

Security and testing add necessary ceremony:

None of this is “wasted”—but it’s exactly where frameworks try to standardize and reduce repetition.

Frameworks cut boilerplate by giving you a default structure and a clear “happy path.” Instead of assembling every piece yourself—routing, configuration, dependency wiring, error handling—you start from patterns that already fit together.

Most frameworks ship with a project template: folders, file naming rules, and baseline configuration. That means you don’t have to write (or re-decide) the same startup plumbing for every app. You add features inside a known shape, rather than inventing the shape first.

A key mechanism is inversion of control. You don’t manually call everything in the right order; the framework runs the app and invokes your code at the right moment—when a request arrives, when a job triggers, when validation runs.

Instead of wiring glue code like “if this route matches, call this handler, then serialize the response,” you implement the handler and let the framework orchestrate the rest.

Frameworks often assume sensible defaults (file locations, naming, standard behaviors). When you follow those conventions, you write less configuration and fewer repetitive mappings. You still can override defaults, but you don’t have to.

Many frameworks include common building blocks—routing, authentication helpers, form validation, logging, ORM integrations—so you don’t re-create the same adapters and wrappers in each project.

By picking a standard approach (project layout, dependency injection style, testing patterns), frameworks reduce the number of “which way should we do it?” decisions—saving time and keeping codebases more consistent.

Conventions over configuration means a framework makes sensible default decisions so you don’t have to write as much “wiring” code. Instead of telling the system how everything is arranged, you follow a set of agreed patterns—and things work.

Most conventions are about where things live and what they’re called:

pages/), reusable components in components/, database migrations in migrations/.users maps to “users” features, or a class named User maps to a users table.products/ and the framework automatically serves /products; add products/[id] and it handles /products/123.With these defaults, you avoid writing repetitive configuration like “register this route,” “map this controller,” or “declare where templates are.”

Conventions aren’t a replacement for configuration—they reduce the need for it. You typically reach for explicit config when you:

Shared conventions make projects easier to navigate. A new teammate can guess where to find a login page, API handler, or database schema change without asking. Reviews get faster because the structure is predictable.

The main cost is onboarding: you’re learning the framework’s “house style.” To avoid confusion later, document deviations from the defaults early (even a short README section like “Routing exceptions” or “Folder structure notes”).

Scaffolding is the practice of generating starter code from a command, so you don’t begin every project by hand-writing the same files, folders, and wiring. Instead of copying old projects or hunting for a “perfect” template, you ask the framework to create a baseline that already follows its preferred patterns.

Depending on the stack, scaffolding can produce anything from a whole project skeleton to specific features:

Generators encode conventions. That means your endpoints, folders, naming, and configuration follow consistent rules across the app (and across teams). You also avoid common omissions—missing routes, unregistered modules, forgotten validation hooks—because the generator knows which pieces must exist together.

The biggest risk is treating generated code as magic. Teams may ship features with code they don’t recognize, or leave unused files behind “just in case,” increasing maintenance and confusion.

Prune aggressively: delete what you don’t need and simplify early, while changes are cheap.

Also keep generators versioned and repeatable (checked into the repo or pinned via tooling) so future scaffolds match today’s conventions—not whatever the tool outputs next month.

Frameworks don’t just reduce boilerplate by giving you a nicer starting point—they reduce it over time by letting you reuse the same building blocks across projects. Instead of rewriting glue code (and re-debugging it), you assemble proven pieces.

Most popular frameworks ship with common needs already wired together:

ORMs and migration tools cut out a big chunk of repetition: connection setup, CRUD patterns, schema changes, and rollback scripts. You still need to design your data model, but you stop rewriting the same SQL bootstrapping and “create table if not exists” flows for every environment.

Authentication and authorization modules reduce risky, bespoke security wiring. A framework’s auth layer often standardizes sessions/tokens, password hashing, role checks, and route protection, so you’re not re-implementing these details per project (or per feature).

On the frontend, template systems and component libraries remove repeated UI structure—navigation, forms, modals, and error states. Consistent components also make your app easier to maintain as it grows.

A good plugin ecosystem lets you add capabilities (uploads, payments, admin panels) through configuration and small integration code, rather than rebuilding the same baseline architecture each time.

Frameworks reduce repetition, but they can also introduce a different kind of boilerplate: the “framework-shaped” code you write to satisfy conventions, lifecycle hooks, and required files.

A framework may do a lot for you implicitly (auto-wiring, magic defaults, reflection, middleware chains). That’s convenient—until you’re debugging. The code you didn’t write can be the hardest to reason about, especially when behavior depends on configuration spread across multiple places.

Most frameworks are optimized for common use cases. If your requirements are unusual—custom authentication flows, nonstandard routing, atypical data models—you may need adapters, wrappers, and workaround code. That glue can feel like boilerplate, and it often ages poorly because it’s tightly coupled to internal framework assumptions.

Frameworks can pull in features you don’t need. Extra middleware, modules, or default abstractions can increase startup time, memory use, or bundle size. The tradeoff is often acceptable for productivity, but it’s worth noticing when a “simple” app ships a lot of machinery.

Major versions can change conventions, configuration formats, or extension APIs. Migration work can become its own form of boilerplate: repeated edits across many files to match new expectations.

Keep custom code close to official extension points (plugins, hooks, middleware, adapters). If you’re rewriting core pieces or copying internal code, the framework may be costing more boilerplate than it saves.

A useful way to separate a library from a framework is control flow: with a library, you call it; with a framework, it calls you.

That “who’s in charge?” difference often decides how much boilerplate you write. When the framework owns the application lifecycle, it can centralize setup and automatically run the repetitive steps you’d otherwise wire together by hand.

Libraries are building blocks. You decide when to initialize them, how to pass data around, how to handle errors, and how to structure files.

That’s great for small or focused apps, but it can increase boilerplate because you’re responsible for glue code:

Frameworks define the happy path for common tasks (request handling, routing, dependency injection, migrations, background jobs). You plug your code into predefined places, and the framework orchestrates the rest.

This inversion of control reduces boilerplate by making defaults the standard. Instead of repeating the same setup in every feature, you follow conventions and override only what’s different.

A library is enough when:

A framework fits better when:

A common sweet spot is framework core + focused libraries. Let the framework handle lifecycle and structure, then add libraries for specialized needs.

Decision factors to weigh: team skills, timelines, deployment constraints, and how much consistency you want across the codebase.

Picking a framework is less about chasing “the least code” and more about choosing the set of defaults that removes your most common repetition—without hiding too much.

Before comparing options, write down what the project demands:

Look past hello-world demos and check:

A framework that saves 200 lines in controllers but forces custom setup for testing, logging, metrics, and tracing often increases repetition overall. Check whether it offers built-in hooks for tests, structured logging, error reporting, and a sensible security posture.

Build one small feature with real requirements: a form/input flow, validation, persistence, auth, and an API response. Measure how many glue files you created and how readable they are.

Popularity can be a signal, but don’t choose solely based on it—choose the framework whose defaults match your most repeated work.

Reducing boilerplate isn’t just about writing less—it’s about making the “important” code easier to see. The goal is to keep routine setup predictable while keeping your app’s decisions explicit.

Most frameworks ship with sensible defaults for routing, logging, formatting, and folder structure. Treat those as the baseline. When you customize, document the reason in the config or README so future changes don’t turn into archaeology.

A useful rule: if you can’t explain the benefit in one sentence, keep the default.

If your team builds the same kinds of apps repeatedly (admin dashboards, APIs, marketing sites), capture the setup once as a template. That includes folder structure, linting, testing, and deployment wiring.

Keep templates small and opinionated; avoid baking in product-specific code. Host them in a repo and reference them in onboarding docs or an internal “start here” page (e.g., /docs/project-templates).

When you notice the same helpers, validation rules, UI patterns, or API clients appearing across repos, move them into a shared package/module. This keeps fixes and improvements flowing to every project and reduces “almost the same” versions.

Use scripts to generate consistent files (env templates, local dev commands) and CI to enforce basics like formatting and unused dependency checks. Automation prevents boilerplate from becoming a recurring manual task.

Scaffolding is helpful, but it often leaves behind unused controllers, sample pages, and stale configs. Schedule quick cleanups: if a file isn’t referenced and doesn’t clarify intent, remove it. Less code is often clearer code.

If a big chunk of your repetition is starting new apps (routes, auth flows, database wiring, admin CRUD), a chat-driven builder can help you generate a consistent baseline faster and then iterate on the parts that actually differentiate your product.

For example, Koder.ai is a vibe-coding platform that creates web, server, and mobile applications from a simple chat—useful when you want to get from requirements to a working skeleton quickly, then export source code and keep full control. Features like Planning Mode (to agree on structure before generating), snapshots with rollback, and deployment/hosting can reduce the “template wrangling” that often turns into boilerplate across teams.

Boilerplate exists because software needs repeatable structure: wiring, configuration, and glue code that makes real features run safely and consistently. A bit of boilerplate can be useful—it documents intent, keeps patterns predictable, and reduces surprises for teammates.

Frameworks reduce repetition mainly by:

Less boilerplate isn’t automatically better. Frameworks can introduce their own required patterns, files, and rules. The goal is not the smallest codebase—it’s the best tradeoff between speed today and maintainability tomorrow.

A simple way to evaluate a framework change: track how long it takes to create a new feature or endpoint with and without the new approach, then compare that to any learning curve, extra dependencies, or constraints.

Audit your current project:

For more practical articles, browse /blog. If you’re evaluating tools or plans, see /pricing.

Boilerplate code is repeated setup and “glue” you write across many projects—startup code, routing, configuration loading, auth/session handling, logging, and standard error handling.

It’s usually not the unique business logic of your app; it’s the consistent scaffolding that helps everything run safely and predictably.

No. Boilerplate is often helpful because it enforces consistency and reduces risk.

It becomes a problem when it grows so large that it slows changes, hides business logic, or encourages copy‑paste drift and mistakes.

It shows up because most applications share non-negotiable needs:

Even “simple” apps need these guardrails to avoid inconsistent behavior and production surprises.

Common hotspots include:

If you’re seeing the same pattern across many files or repos, it’s likely boilerplate.

Too much boilerplate increases long-term cost:

A good signal is when small policy changes (e.g., an error format) become a multi-file scavenger hunt.

Frameworks reduce boilerplate by providing a “happy path”:

You write the feature-specific parts; the framework handles the repeatable wiring.

Inversion of control means you don’t manually wire every step in the right order. Instead, you implement handlers/hooks, and the framework calls them at the correct time (on a request, during validation, on job execution).

Practically, this eliminates a lot of “if route matches then…” and “initialize X then pass to Y…” glue code because the framework owns the lifecycle.

Conventions over configuration means the framework assumes sensible defaults (folder locations, naming, routing patterns), so you don’t have to write repetitive mappings.

You typically add explicit config when you need something non-standard—legacy URLs, special security policies, or third-party integrations where defaults can’t guess your requirements.

Scaffolding/code generation creates starter structures (project templates, CRUD endpoints, auth flows, migrations) so you don’t hand-write the same files repeatedly.

Best practices:

Ask two questions:

Also evaluate documentation quality, plugin ecosystem maturity, and upgrade stability—frequent breaking changes can reintroduce boilerplate via repeated migrations and adapter rewrites.