Oct 24, 2025·8 min

Why Database Indexing Is the Most Important Performance Boost

Learn how database indexes cut query time, when they help (and hurt), and practical steps to design, test, and maintain indexes for real apps.

Learn how database indexes cut query time, when they help (and hurt), and practical steps to design, test, and maintain indexes for real apps.

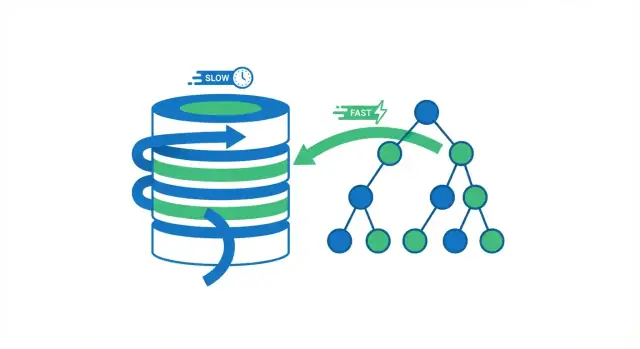

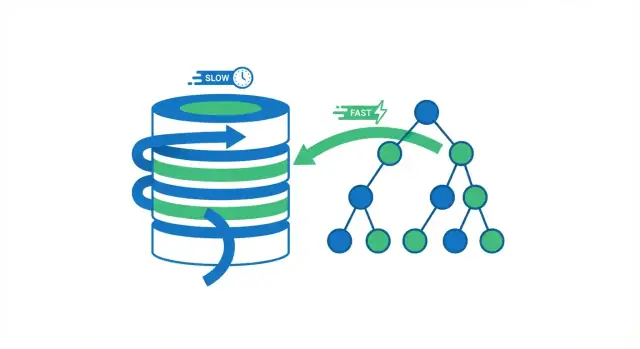

A database index is a separate lookup structure that helps the database find rows faster. It’s not a second copy of your table. Think of it like the index pages in a book: you use the index to jump close to the right place, then read the exact page (row) you need.

Without an index, the database often has only one safe option: read through many rows to check which ones match your query. That can be fine when a table has a few thousand rows. As the table grows into millions of rows, “check more rows” turns into more disk reads, more memory pressure, and more CPU work—so the same query that used to feel instant starts to drag.

Indexes reduce the amount of data the database must inspect to answer questions like “find the order with ID 123” or “fetch users with this email.” Instead of scanning everything, the database follows a compact structure that narrows the search quickly.

But indexing isn’t a universal fix. Some queries still need to process lots of rows (broad reports, low-selectivity filters, heavy aggregations). And indexes have real costs: extra storage and slower writes, because inserts and updates must also update the index.

You’ll see:

When a database runs a query, it has two broad options: scan the whole table row by row, or jump directly to the rows that match. Most indexing wins come from avoiding unnecessary reads.

A full table scan is exactly what it sounds like: the database reads every row, checks whether it matches the WHERE condition, and only then returns results. That’s acceptable for small tables, but it gets slower in a predictable way as the table grows—more rows means more work.

Using an index, the database can often avoid reading most rows. Instead, it consults the index first (a compact structure built for searching) to find where the matching rows live, then reads only those specific rows.

Think of a book. If you want every page mentioning “photosynthesis,” you could read the entire book cover to cover (full scan). Or you could use the book’s index, jump to the pages listed, and read only those sections (index lookup). The second approach is faster because you skip almost all the pages.

Databases spend a lot of time waiting on reads—especially when data isn’t already in memory. Cutting the number of rows (and pages) the database has to touch typically reduces:

Indexing helps most when data is large and the query pattern is selective (for example, fetching 20 matching rows out of 10 million). If your query returns most rows anyway, or the table is small enough to fit comfortably in memory, a full scan may be just as fast—or even faster.

Indexes work because they organize values so the database can jump close to what you want instead of checking every row.

The most common index structure in SQL databases is the B-tree (often written as “B-tree” or “B+tree”). Conceptually:

Because it’s sorted, a B-tree is great for both equality lookups (WHERE email = ...) and range queries (WHERE created_at >= ... AND created_at < ...). The database can navigate to the right neighborhood of values and then scan forward in order.

People say B-tree lookups are “logarithmic.” Practically, that means this: as your table grows from thousands to millions of rows, the number of steps to find a value grows slowly, not proportionally.

Instead of “twice the data means twice the work,” it’s more like “a lot more data means only a few extra navigation steps,” because the database follows pointers through a small number of levels in the tree.

Some engines also offer hash indexes. These can be very fast for exact equality checks because the value is transformed into a hash and used to find the entry directly.

The tradeoff: hash indexes typically don’t help with ranges or ordered scans, and availability/behavior varies across databases.

PostgreSQL, MySQL/InnoDB, SQL Server, and others store and use indexes differently (page size, clustering, included columns, visibility checks). But the core concept carries over: indexes create a compact, navigable structure that lets the database locate matching rows with far less work than scanning the whole table.

Indexes don’t speed up “SQL” in general—they speed up specific access patterns. When an index matches how your query filters, joins, or sorts, the database can jump straight to relevant rows instead of reading the whole table.

1) WHERE filters (especially on selective columns)

If your query often narrows a large table down to a small set of rows, an index is usually the first place to look. A classic example is looking up a user by an identifier.

Without an index on users.email, the database may have to scan every row:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE email = '[email protected]';

With an index on email, it can locate the matching row(s) quickly and stop.

2) JOIN keys (foreign keys and referenced keys)

Joins are where “small inefficiencies” turn into big costs. If you join orders.user_id to users.id, indexing the join columns (typically orders.user_id and the primary key users.id) helps the database match rows without repeatedly scanning.

3) ORDER BY (when you want results already sorted)

Sorting is expensive when the database must collect lots of rows and sort them after the fact. If you frequently run:

SELECT * FROM orders WHERE user_id = 42 ORDER BY created_at DESC;

an index that aligns with user_id and the sort column can let the engine read rows in the needed order rather than sorting a big intermediate result.

4) GROUP BY (when grouping aligns with an index)

Grouping can benefit when the database can read data in grouped order. It’s not a guarantee, but if you commonly group by a column that’s also used for filtering (or is naturally clustered in the index), the engine may do less work.

B-tree indexes are especially good at range conditions—think dates, prices, and “between” queries:

SELECT * FROM orders

WHERE created_at \u003e= '2025-01-01' AND created_at \u003c '2025-02-01';

For dashboards, reports, and “recent activity” screens, this pattern is everywhere, and an index on the range column often produces an immediate improvement.

The theme is simple: indexes help most when they mirror how you search and sort. If your queries line up with those access patterns, the database can do targeted reads instead of broad scans.

An index helps most when it sharply narrows how many rows the database has to touch. That property is called selectivity.

Selectivity is basically: how many rows match a given value? A highly selective column has many distinct values, so each lookup matches few rows.

email, user_id, order_number (often unique or close to it)is_active, is_deleted, status with a few common valuesWith high selectivity, an index can jump straight to a small set of rows. With low selectivity, the index points to a huge chunk of the table—so the database still has to read and filter a lot.

Consider a table with 10 million rows and a column is_deleted where 98% are false. An index on is_deleted doesn’t save much for:

SELECT * FROM orders WHERE is_deleted = false;

The “match set” is still almost the whole table. Using the index can even be slower than a sequential scan because the engine does extra work hopping between index entries and table pages.

Query planners estimate costs. If an index won’t reduce work enough—because too many rows match, or because the query also needs most columns—they may choose a full table scan.

Data distribution isn’t fixed. A status column might start evenly distributed, then drift so one value dominates. If statistics aren’t updated, the planner can make poor decisions, and an index that used to help may stop paying off.

Single-column indexes are a good start, but many real queries filter on one column and sort or filter on another. That’s where composite (multi-column) indexes shine: one index can serve multiple parts of the query.

Most databases (especially with B-tree indexes) can only use a composite index efficiently from the leftmost columns forward. Think of the index as being sorted first by column A, then within that by column B, and so on.

That means:

account_id and then sorting or filtering by created_atcreated_at (because it’s not the leftmost column)A common workload is “show me the most recent events for this account.” This query pattern:

SELECT id, created_at, type

FROM events

WHERE account_id = ?

ORDER BY created_at DESC

LIMIT 50;

often benefits enormously from:

CREATE INDEX events_account_created_at

ON events (account_id, created_at);

The database can jump straight to one account’s portion of the index and read rows in time order, instead of scanning and sorting a large set.

A covering index contains all columns the query needs, so the database can return results from the index without looking up the table rows (fewer reads, less random I/O).

Be careful: adding extra columns can make an index large and expensive.

Wide composite indexes can slow writes and consume lots of storage. Add them only for specific high-value queries, and verify with an EXPLAIN plan and real measurements before and after.

Indexes are often described as “free speed,” but they aren’t free. Index structures must be maintained every time the underlying table changes, and they consume real resources.

When you INSERT a new row, the database doesn’t just write the row once—it also inserts corresponding entries into each index on that table. The same goes for DELETE, and many UPDATEs.

This is why “more indexes” can noticeably slow down write-heavy workloads. An UPDATE that touches an indexed column can be especially expensive: the database may need to remove the old index entry and add a new one (and in some engines, this can trigger extra page splits or internal rebalancing). If your app does a lot of writes—order events, sensor data, audit logs—indexing everything can make the database feel sluggish even if reads are fast.

Each index takes disk space. On large tables, indexes can rival (or exceed) the table size, especially if you have multiple overlapping indexes.

It also affects memory. Databases rely heavily on caching; if your working set includes several large indexes, the cache must hold more pages to stay fast. Otherwise, you’ll see more disk I/O and less predictable performance.

Indexing is about choosing what to accelerate. If your workload is read-heavy, more indexes can be worth it. If it’s write-heavy, prioritize indexes that support your most important queries and avoid duplicates. A useful rule: add an index only when you can name the query it helps—and verify that the read speed gain outweighs the write and maintenance cost.

Adding an index seems like it should help—but you can (and should) verify it. The two tools that make this concrete are the query plan (EXPLAIN) and real before/after measurements.

Run EXPLAIN (or EXPLAIN ANALYZE) on the exact query you care about.

EXPLAIN ANALYZE): If the plan estimated 100 rows but actually touched 100,000, the optimizer made a bad guess—often because stats are stale or the filter is less selective than expected.ORDER BY, that sort might disappear, which can be a big win.Benchmark the query with the same parameters, on representative data size, and capture both latency and rows processed.

Be careful with caching: the first run may be slower because data isn’t in memory yet; repeated runs may look “fixed” even without an index. To avoid fooling yourself, compare multiple runs and focus on whether the plan changes (index used, fewer rows read) in addition to raw time.

If EXPLAIN ANALYZE shows fewer rows touched and fewer expensive steps (like sorts), you’ve proven the index helps—not just hoped it does.

You can add the “right” index and still see no speed-up if the query is written in a way that prevents the database from using it. These issues are often subtle, because the query still returns correct results—it’s just forced into a slower plan.

1) Leading wildcards

When you write:

WHERE name LIKE '%term'

the database can’t use a normal B-tree index to jump to the right starting point, because it doesn’t know where in the sorted order “%term” begins. It often falls back to scanning lots of rows.

Alternatives:

WHERE name LIKE 'term%'.2) Functions on indexed columns

This looks harmless:

WHERE LOWER(email) = '[email protected]'

But LOWER(email) changes the expression, so the index on email can’t be used directly.

Alternatives:

WHERE email = ....LOWER(email).Implicit type casts: Comparing different data types can force the database to cast one side, which can disable an index. Example: comparing an integer column to a string literal.

Mismatched collations/encodings: If the comparison uses a different collation than the index was built with (common in text columns across different locales), the optimizer may avoid the index.

LIKE '%x')?LOWER(col), DATE(col), CAST(col))?EXPLAIN to confirm what the database actually chose?Indexes aren’t “set it and forget it.” Over time, data changes, query patterns shift, and the physical shape of tables and indexes drifts. A well-chosen index can slowly become less effective—or even harmful—if you don’t maintain it.

Most databases rely on a query planner (optimizer) to choose how to run a query: which index to use, which join order to pick, and whether an index lookup is worth it. To make those decisions, the planner uses statistics—summaries about value distributions, row counts, and data skew.

When statistics are stale, the planner’s row estimates can be wildly wrong. That leads to bad plan choices, like picking an index that returns far more rows than expected, or skipping an index that would have been faster.

Routine fix: schedule regular stats updates (often called “ANALYZE” or similar). After large data loads, major deletes, or significant churn, refresh stats sooner.

As rows are inserted, updated, and deleted, indexes can accumulate bloat (extra pages that no longer hold useful data) and fragmentation (data spread out in a way that increases I/O). The result is bigger indexes, more reads, and slower scans—especially for range queries.

Routine fix: periodically rebuild or reorganize heavily used indexes when they’ve grown disproportionately or performance drifts. Exact tooling and impact vary by database, so treat this as a measured operation, not a blanket rule.

Set up monitoring for:

That feedback loop helps you catch when maintenance is needed—and when an index should be adjusted or removed. For more on validating improvements, see /blog/how-to-prove-an-index-helps-explain-and-measurements.

Adding an index should be a deliberate change, not a guess. A lightweight workflow keeps you focused on measurable wins and prevents “index sprawl.”

Start with evidence: slow-query logs, APM traces, or user reports. Pick one query that is both slow and frequent—a rare 10‑second report matters less than a common 200 ms lookup.

Capture the exact SQL and the parameter pattern (for example: WHERE user_id = ? AND status = ? ORDER BY created_at DESC LIMIT 50). Small differences change which index helps.

Record current latency (p50/p95), rows scanned, and CPU/IO impact. Save the current plan output (e.g., EXPLAIN / EXPLAIN ANALYZE) so you can compare later.

Choose columns that match how the query filters and sorts. Prefer the minimal index that makes the plan stop scanning huge ranges.

Test in staging with production-like data volume. Indexes can look great on small datasets and disappoint at scale.

On large tables, use online options where supported (for example, PostgreSQL CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY). Schedule changes during lower traffic if your database may lock writes.

Re-run the same query and compare:

If the index increases write cost or bloats memory, remove it cleanly (e.g., DROP INDEX CONCURRENTLY where available). Keep the migration reversible.

In the migration or schema notes, write which query the index serves and what metric improved. Future you (or a teammate) will know why it exists and when it’s safe to delete.

If you’re building a new service and want to avoid “index sprawl” early, Koder.ai can help you iterate faster on the full loop above: generate a React + Go + PostgreSQL app from chat, adjust schema/index migrations as requirements change, and then export the source code when you’re ready to take over manually. In practice, that makes it easier to go from “this endpoint is slow” to “here’s the EXPLAIN plan, the minimal index, and a reversible migration” without waiting on a full traditional pipeline.

Indexes are a huge lever, but they’re not a magic “make it fast” button. Sometimes the slow part of a request happens after the database finds the right rows—or your query pattern makes indexing the wrong first move.

If your query already uses a good index yet still feels slow, look for these common culprits:

OFFSET 999000 can be slow even with indexes. Prefer keyset pagination (e.g., “give me rows after the last seen id/timestamp”).SELECT *) or returning tens of thousands of records can bottleneck on network, JSON serialization, or application processing.LIMIT, and page results intentionally.If you want a deeper method for diagnosing bottlenecks, pair this with the workflow in /blog/how-to-prove-an-index-helps.

Don’t guess. Measure where time is spent (database execution vs. rows returned vs. app code). If the database is fast but the API is slow, more indexes won’t help.

A database index is a separate data structure (often a B-tree) that stores selected column values in a searchable, sorted form with pointers back to table rows. The database uses it to avoid reading most of the table when answering selective queries.

It’s not a second full copy of the table, but it does duplicate some column data plus metadata, which is why it consumes extra storage.

Without an index, the database may have to do a full table scan: read many (or all) rows and check each one against your WHERE clause.

With an index, it can often jump directly to the matching row locations and read only those rows, reducing disk I/O, CPU filter work, and cache pressure.

A B-tree index keeps values sorted and organized into pages that point to other pages, so the database can navigate quickly to the right “neighborhood” of values.

That’s why B-trees work well for both:

WHERE email = ...)WHERE created_at >= ... AND created_at < ...)Hash indexes can be very fast for exact equality (=) because they hash a value and jump to its bucket.

Tradeoffs:

In many real workloads, B-trees are the default because they support more query patterns.

Indexes usually help most for:

WHERE filters (few rows match)JOIN keys (foreign keys and referenced keys)ORDER BY that matches an index order (can avoid a sort)GROUP BY cases when reading in grouped order reduces workIf a query returns a large fraction of the table, the benefit is often small.

Selectivity is “how many rows match a given value.” Indexes pay off when a predicate narrows a large table down to a small result set.

Low-selectivity columns (e.g., is_deleted, is_active, small status enums) often match huge portions of the table. In those cases, using the index can be slower than scanning because the engine still has to fetch and filter many rows.

Because the optimizer estimates that using it won’t reduce work enough.

Common reasons include:

In most B-tree implementations, the index is effectively sorted by the first column, then within that by the second, etc. So the database can efficiently use the index starting from the leftmost column(s).

Example:

(account_id, created_at) is great for WHERE account_id = ? plus time filtering/sorting.created_at (since it’s not leftmost).A covering index includes all columns needed by the query so the database can return results from the index without fetching the table rows.

Benefits:

Costs:

Use covering indexes for specific high-value queries, not “just in case.”

Check two things:

EXPLAIN / EXPLAIN ANALYZE and confirm the plan changes (e.g., Seq Scan → Index Scan/Seek, fewer rows read, sort step removed).Also watch write performance, since new indexes can slow INSERT/UPDATE/DELETE.