Oct 15, 2025·8 min

Why Document Databases Win When Data Models Change Often

Learn why document databases fit rapidly changing data models: flexible schemas, easier iteration, natural JSON storage, and trade-offs to plan for.

Learn why document databases fit rapidly changing data models: flexible schemas, easier iteration, natural JSON storage, and trade-offs to plan for.

A document database stores data as self-contained “documents,” usually in a JSON-like format. Instead of spreading one business object across multiple tables, a single document can hold everything about it—fields, subfields, and arrays—much like the way many apps already represent data in code.

users collection or an orders collection).Documents in the same collection don’t have to look identical. One user document might have 12 fields, another might have 18, and both can still live side by side.

Imagine a user profile. You start with name and email. Next month, marketing wants preferred_language. Then customer success asks for timezone and subscription_status. Later you add social_links (an array) and privacy_settings (a nested object).

In a document database, you can usually start writing the new fields immediately. Older documents can remain as-is until you choose to backfill them (or not).

This flexibility can speed up product work, but it shifts responsibility to your application and team: you’ll need clear conventions, optional validation rules, and thoughtful query design to avoid messy, inconsistent data.

Next, we’ll look at why some models change so often, how flexible schemas reduce friction, how documents map to real app queries, and the trade-offs to weigh before choosing document storage over relational—or using a hybrid approach.

Data models rarely stay still because the product rarely stays still. What starts as “just store a user profile” quickly turns into preferences, notifications, billing metadata, device info, consent flags, and a dozen other details that didn’t exist in the first version.

Most model churn is simply the result of learning. Teams add fields when they:

These changes are often incremental and frequent—small additions that are hard to schedule as formal “big migrations.”

Real databases contain history. Old records keep the shape they were written with, while new records adopt the latest shape. You might have customers created before marketing_opt_in existed, orders created before delivery_instructions was supported, or events logged before a new source field was defined.

So you’re not “changing one model”—you’re supporting multiple versions at once, sometimes for months.

When multiple teams ship in parallel, the data model becomes a shared surface area. A payments team may add fraud signals while a growth team adds attribution data. In microservices, each service may store a “customer” concept with different needs, and those needs evolve independently.

Without coordination, the “single perfect schema” becomes a bottleneck.

External systems often send payloads that are partially known, nested, or inconsistent: webhook events, partner metadata, form submissions, device telemetry. Even when you normalize the important pieces, you frequently want to keep the original structure for audit, debugging, or future use.

All of these forces push teams toward storage that tolerates change gracefully—especially when shipping speed matters.

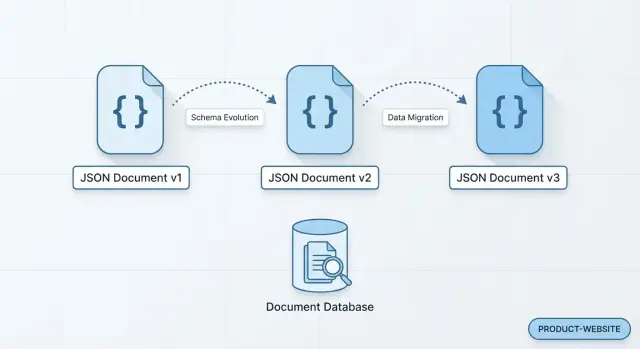

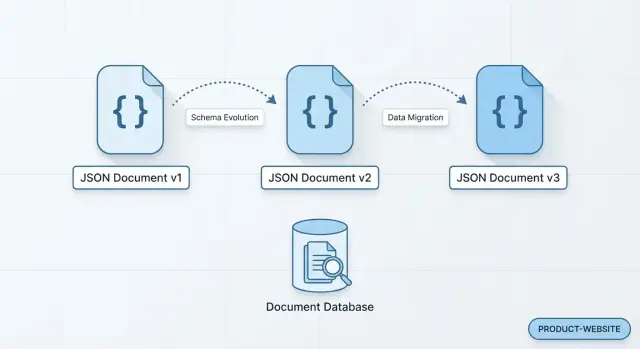

When a product is still finding its shape, the data model is rarely “done.” New fields appear, old ones become optional, and different customers may need slightly different information. Document databases are popular in these moments because they let you evolve data without turning every change into a database migration project.

With JSON documents, adding a new property can be as simple as writing it on new records. Existing documents can remain untouched until you decide it’s worth backfilling. That means a small experiment—like collecting a new preference setting—doesn’t require coordinating a schema change, a deploy window, and a backfill job just to start learning.

Sometimes you genuinely have variants: a “free” account has fewer settings than an “enterprise” account, or one product type needs extra attributes. In a document database, it can be acceptable for documents in the same collection to have different shapes, as long as your application knows how to interpret them.

Rather than forcing everything into a single rigid structure, you can keep:

id, userId, createdAt)Flexible schemas don’t mean “no rules.” A common pattern is to treat missing fields as “use a default.” Your application can apply sensible defaults at read time (or set them at write time), so older documents still behave correctly.

Feature flags often introduce temporary fields and partial rollouts. Flexible schemas make it easier to ship a change to a small cohort, store extra state only for flagged users, and iterate quickly—without blocking on schema work before you can test an idea.

Many product teams naturally think in terms of “a thing the user sees on a screen.” A profile page, an order detail view, a project dashboard—each one usually maps to a single app object with a predictable shape. Document databases support that mental model by letting you store that object as a single JSON document, with far fewer translations between application code and storage.

With relational tables, the same feature often gets split across multiple tables, foreign keys, and join logic. That structure is powerful, but it can feel like extra ceremony when the app already holds the data as a nested object.

In a document database, you can often persist the object almost as-is:

user document that matches your User class/typeproject document that matches your Project state modelLess translation usually means fewer mapping bugs and quicker iteration when fields change.

Real app data is rarely flat. Addresses, preferences, notification settings, saved filters, UI flags—these are all naturally nested.

Storing nested objects inside the parent document keeps related values close, which helps for “one record = one screen” queries: fetch one document, render one view. That can reduce the need for joins and the performance surprises that come with them.

When each feature team owns the shape of its documents, responsibilities become clearer: the team that ships the feature also evolves its data model. That tends to work well in microservices or modular architectures, where independent changes are a constant, not an exception.

Document databases often fit teams that ship frequently because small data additions rarely require a coordinated “stop the world” database change.

If a product manager asks for “just one more attribute” (say, preferredLanguage or marketingConsentSource), a document model typically lets you start writing that field immediately. You don’t always need to schedule a migration, lock tables, or negotiate a release window across multiple services.

That reduces the number of tasks that can block a sprint: the database stays usable while the application evolves.

Adding optional fields to JSON-like documents is commonly backward compatible:

This pattern tends to make deployments calmer: you can roll out the write path first (start storing the new field), then update read paths and UI later—without having to update every existing document immediately.

Real systems rarely upgrade all clients at once. You might have:

With document databases, teams often design for “mixed versions” by treating fields as additive and optional. Newer writers can add data without breaking older readers.

A practical deployment pattern looks like this:

This approach keeps velocity high while reducing coordination costs between database changes and application releases.

One reason teams like document databases is that you can model data the way your application most often reads it. Instead of spreading a concept across many tables and stitching it back together later, you can store a “whole” object (often as JSON documents) in one place.

Denormalization means duplicating or embedding related fields so common queries can be answered from a single document read.

For example, an order document might include customer snapshot fields (name, email at the time of purchase) and an embedded array of line items. That design can make “show my last 10 orders” fast and simple, because the UI doesn’t need multiple lookups just to render a page.

When data for a screen or API response lives in one document, you often get:

This tends to reduce latency for read-heavy paths—especially common in product feeds, profiles, carts, and dashboards.

Embedding is usually helpful when:

Referencing is often better when:

There’s no universally “best” document shape. A model optimized for one query can make another slower (or more expensive to update). The most reliable approach is to start from your real queries—what your app actually needs to fetch—and shape documents around those read paths, then revisit the model as usage evolves.

Schema-on-read means you don’t have to define every field and table shape before you can store data. Instead, your application (or analytics query) interprets each document’s structure when it reads it. Practically, that lets you ship a new feature that adds preferredPronouns or a new nested shipping.instructions field without coordinating a database migration first.

Most teams still have an “expected shape” in mind—it’s just enforced later and more selectively. One customer document might have phone, another might not. An older order might store discountCode as a string, while newer orders store a richer discount object.

Flexibility doesn’t have to mean chaos. Common approaches:

id, createdAt, or status, and restrict types for high-risk fields.A little consistency goes a long way:

camelCase, timestamps in ISO-8601)schemaVersion: 3) so readers can handle old and new shapes safelyAs a model stabilizes—usually after you’ve learned what fields are truly core—introduce stricter validation around those fields and critical relationships. Keep optional or experimental fields flexible, so the database still supports rapid iteration without constant migrations.

When your product changes weekly, it’s not just the “current” shape of data that matters. You also need a reliable story of how it got there. Document databases are a natural fit for keeping change history because they store self-contained records that can evolve without forcing a rewrite of everything that came before.

A common approach is to store changes as an event stream: each event is a new document you append (rather than updating old rows in place). For example: UserEmailChanged, PlanUpgraded, or AddressAdded.

Because each event is its own JSON document, you can capture the full context at that moment—who did it, what triggered it, and any metadata you’ll want later.

Event definitions rarely stay stable. You might add source="mobile", experimentVariant, or a new nested object like paymentRiskSignals. With document storage, old events can simply omit those fields, and new events can include them.

Your readers (services, jobs, dashboards) can default missing fields safely, instead of backfilling and migrating millions of historical records just to introduce one extra attribute.

To keep consumers predictable, many teams include a schemaVersion (or eventVersion) field in each document. That enables gradual rollout:

A durable history of “what happened” is useful beyond audits. Analytics teams can rebuild state at any point in time, and support engineers can trace regressions by replaying events or inspecting the exact payload that led to a bug. Over months, that makes root-cause analysis faster and reporting more trustworthy.

Document databases make change easier, but they don’t remove design work—they shift it. Before you commit, it helps to be clear about what you’re trading for that flexibility.

Many document databases support transactions, but multi-entity (multi-document) transactions may be limited, slower, or more expensive than in a relational database—especially at high scale. If your core workflow requires “all-or-nothing” updates across several records (for example, updating an order, inventory, and ledger entry together), check how your database handles this and what it costs in performance or complexity.

Because fields are optional, teams can accidentally create several “versions” of the same concept in production (e.g., address.zip vs address.postalCode). That can break downstream features and make bugs harder to spot.

A practical mitigation is to define a shared contract for key document types (even if it’s lightweight) and add optional validation rules where it matters most—such as payment status, pricing, or permissions.

If documents evolve freely, analytics queries can become messy: analysts end up writing logic for multiple field names and missing values. For teams that rely on heavy reporting, you may need a plan such as:

Embedding related data (like customer snapshots inside orders) speeds up reads, but duplicates information. When a shared piece of data changes, you must decide: update everywhere, keep history, or tolerate temporary inconsistency. That decision should be intentional—otherwise you risk subtle data drift.

Document databases are a great fit when change is frequent, but they reward teams that treat modeling, naming, and validation as ongoing product work—not a one-time setup.

Document databases store data as JSON documents, which makes them a natural fit when your fields are optional, change frequently, or vary by customer, device, or product line. Instead of forcing every record into the same rigid table shape, you can evolve the data model gradually while keeping teams moving.

Product data rarely stays still: new sizes, materials, compliance flags, bundles, regional descriptions, and marketplace-specific fields show up constantly. With nested data in JSON documents, a “product” can keep core fields (SKU, price) while allowing category-specific attributes without weeks of schema redesign.

Profiles often start small and grow: notification settings, marketing consents, onboarding answers, feature flags, and personalization signals. In a document database, users can have different sets of fields without breaking existing reads. That schema flexibility also helps agile development, where experiments may add and remove fields quickly.

Modern CMS content isn’t just “a page.” It’s a mix of blocks and components—hero sections, FAQs, product carousels, embeds—each with its own structure. Storing pages as JSON documents lets editors and developers introduce new component types without migrating every historical page immediately.

Telemetry often varies by firmware version, sensor package, or manufacturer. Document databases handle these evolving data models well: each event can include only what the device knows, while schema-on-read lets analytics tools interpret fields when present.

If you’re deciding between NoSQL vs SQL, these are the scenarios where document databases tend to deliver faster iteration with less friction.

When your data model is still settling, “good enough and easy to change” beats “perfect on paper.” These practical habits help you keep momentum without turning your database into a junk drawer.

Begin each feature by writing down the top reads and writes you expect to happen in production: the screens you render, the API responses you return, and the updates you perform most often.

If one user action regularly needs “order + items + shipping address,” model a document that can serve that read with minimal extra fetching. If another action needs “all orders by status,” make sure you can query or index for that path.

Embedding (nesting) data is great when:

Referencing (storing IDs) is safer when:

You can mix both: embed a snapshot for read speed, reference the source of truth for updates.

Even with schema flexibility, add lightweight rules for the fields you depend on (types, required IDs, allowed statuses). Include a schemaVersion (or docVersion) field so your application can handle older documents gracefully and migrate them over time.

Treat migrations as periodic maintenance, not a one-time event. As the model matures, schedule small backfills and cleanups (unused fields, renamed keys, denormalized snapshots) and measure impact before and after. A simple checklist and a lightweight migration script go a long way.

Choosing between a document database and a relational database is less about “which is better” and more about what kind of change your product experiences most often.

Document databases are a strong fit when your data shape changes frequently, different records may have different fields, or teams need to ship features without coordinating a schema migration every sprint.

They’re also a good match when your application naturally works with “whole objects” like an order (customer info + items + delivery notes) or a user profile (settings + preferences + device info) stored together as JSON documents.

Relational databases shine when you need:

If your team’s work is mostly optimizing cross-table queries and analytics, SQL is often the simpler long-term home.

Many teams use both: relational for the “core system of record” (billing, inventory, entitlements) and a document store for fast-evolving or read-optimized views (profiles, content metadata, product catalogs). In microservices, this can align naturally: each service picks the storage model that fits its boundaries.

It’s also worth remembering that “hybrid” can exist inside a relational database. For example, PostgreSQL can store semi-structured fields using JSON/JSONB alongside strongly-typed columns—useful when you want transactional consistency and a safe place for evolving attributes.

If your schema is changing weekly, the bottleneck is often the end-to-end loop: updating models, APIs, UI, migrations (if any), and safely rolling out changes. Koder.ai is designed for that kind of iteration. You can describe the feature and data shape in chat, generate a working web/backend/mobile implementation, and then refine it as requirements evolve.

In practice, teams often start with a relational core (Koder.ai’s backend stack is Go with PostgreSQL) and use document-style patterns where they make sense (for example, JSONB for flexible attributes or event payloads). Koder.ai’s snapshots and rollback also help when an experimental data shape needs to be reverted quickly.

Run a short evaluation before committing:

If you’re comparing options, keep the scope tight and time-boxed—then expand once you see which model helps you ship with fewer surprises. For more on evaluating storage trade-offs, see /blog/document-vs-relational-checklist.

A document database stores each record as a self-contained JSON-like document (including nested objects and arrays). Instead of splitting one business object across multiple tables, you often read and write the whole object in one operation, typically within a collection (e.g., users, orders).

In fast-moving products, new attributes show up constantly (preferences, billing metadata, consent flags, experiment fields). Flexible schemas let you start writing new fields immediately, keep old documents unchanged, and optionally backfill later—so small changes don’t turn into big migration projects.

Not necessarily. Most teams still keep an “expected shape,” but enforcement shifts to:

This keeps flexibility while reducing messy, inconsistent documents.

Treat new fields as additive and optional:

This supports mixed data versions in production without downtime-heavy migrations.

Model for your most common reads: if a screen or API response needs “order + items + shipping address,” store those together in one document when practical. This can reduce round trips and avoid join-heavy assembly, improving latency on read-heavy paths.

Use embedding when the child data is usually read with the parent and is bounded in size (e.g., up to 20 items). Use referencing when the related data is large/unbounded, shared across many parents, or changes frequently.

You can also mix both: embed a snapshot for fast reads and keep a reference to the source of truth for updates.

It helps by making “add a field” deployments more backward-compatible:

This is especially useful with multiple services or mobile clients on older versions.

Include lightweight guardrails:

id, createdAt, )Common approaches include append-only event documents (each change is a new document) and versioning (eventVersion/schemaVersion). New fields can be added to future events without rewriting history, while consumers read multiple versions during gradual rollouts.

Key trade-offs include:

Many teams adopt a hybrid: relational for strict “system of record” data and document storage for fast-evolving or read-optimized models.

statuscamelCase, ISO-8601 timestamps)schemaVersion/docVersion fieldThese steps prevent drift like address.zip vs address.postalCode.