Aug 30, 2025·8 min

Why Eventual Consistency Works in Many Real‑World Apps

Eventual consistency often delivers faster, more available apps. Learn when it’s fine, how to design around it, and when you need stronger guarantees.

Eventual consistency often delivers faster, more available apps. Learn when it’s fine, how to design around it, and when you need stronger guarantees.

“Consistency” is a simple question: if two people look at the same piece of data, do they see the same thing at the same time? For example, if you change your shipping address, will your profile page, checkout page, and customer support screen all show the new address immediately?

With eventual consistency, the answer is: not always immediately—but it will converge. The system is designed so that, after a short delay, every copy settles on the same latest value.

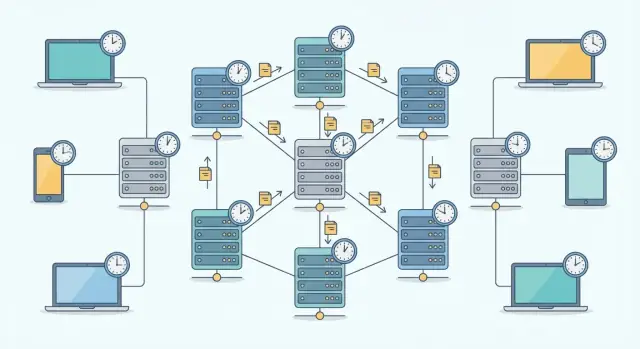

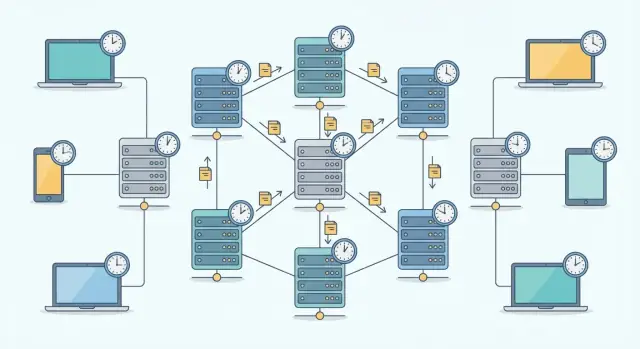

When you save a change, that update needs to travel. In large apps, data isn’t stored in only one place. It’s replicated—kept as multiple copies (called replicas) on different servers or in different regions.

Why keep copies?

Those replicas don’t update in perfect lockstep. If you update your username, one replica may apply the change instantly while another applies it a moment later. During that window, some users (or even you, from a different screen) might briefly see the old value.

Eventual consistency can feel suspicious because we’re used to thinking computers are exact. But the system isn’t losing your update—it’s prioritizing availability and speed, then letting the rest of the copies catch up.

A useful framing is:

That “soon” might be milliseconds, seconds, or occasionally longer during outages or heavy load. Good product design makes this delay understandable and rarely noticeable.

Instant agreement sounds ideal: every server, in every region, always showing the exact same data at the exact same moment. For small, single-database apps, that’s often achievable. But as products grow—more users, more servers, more locations—“perfectly synchronized everywhere” becomes expensive and sometimes unrealistic.

When an app runs across multiple servers or regions, data has to travel over networks that introduce delay and occasional failure. Even if most requests are fast, the slowest links (or a temporarily disconnected region) dictate how long it takes to confirm that everyone has the newest update.

If the system insists on instant agreement, it may need to:

That can turn a minor network issue into a noticeable user problem.

To guarantee immediate consistency, many designs require coordination—effectively a group decision—before data is considered committed. Coordination is powerful, but it adds round trips and makes performance less predictable. If a key replica is slow, the whole operation can slow down with it.

This is the trade-off commonly summarized by the CAP theorem: under network partitions, systems must choose between being available (serving requests) and being strictly consistent (never showing disagreement). Many real applications prioritize staying responsive.

Replication isn’t only for handling more traffic. It’s also insurance against failures: servers crash, regions degrade, deployments go wrong. With replicas, the app can keep accepting orders, messages, and uploads even if one part of the system is unhealthy.

Choosing eventual consistency is often a deliberate choice between:

Many teams accept short-lived differences because the alternative is slower experiences or outages at the worst times—like peak traffic, promotions, or incidents.

Eventual consistency is easiest to notice when you use the same app from more than one place.

You “like” a post on your phone. The heart icon fills in right away, and the like count might jump from 10 to 11.

A minute later, you open the same post on your laptop and… it still shows 10 likes. Or the heart is not filled yet. Nothing is “broken” in the long-term sense—the update just hasn’t reached every copy of the data.

Most of the time these delays are short (often fractions of a second). But they can spike when networks are slow, when a data center is briefly unreachable, or when the service is handling unusually high traffic. During those moments, different parts of the system may temporarily disagree.

From a user’s point of view, eventual consistency usually shows up as one of these patterns:

These effects are most noticeable around counters (likes, views), activity feeds, notifications, and search results—places where data is replicated widely for speed.

Eventual consistency doesn’t mean “anything goes.” It means the system is designed to converge: once the temporary disruption passes and updates have time to propagate, every replica settles on the same final state.

In the “like” example, both devices will eventually agree that you liked the post and that the count is 11. The timing may vary, but the destination is the same.

When apps handle these short-lived inconsistencies thoughtfully—clear UI feedback, sensible refresh behavior, and avoiding scary error messages—most users barely notice what’s happening under the hood.

Eventual consistency is a trade-off: the system may show slightly different data in different places for a short time, but it buys you very practical advantages. For many products, those advantages matter more than instant agreement—especially once you have users across regions and multiple replicas.

With replication, data lives in more than one place. If one node or even an entire region has issues, other replicas can continue serving reads and accepting writes. That means fewer “hard down” incidents and fewer features that break completely during partial outages.

Instead of blocking everyone until every copy agrees, the app keeps working and converges later.

Coordinating every write across distant servers adds delay. Eventual consistency reduces that coordination, so the system can often:

The result is a snappier feel—page loads, timeline refreshes, “like” counts, and inventory lookups can be served with much lower latency. Yes, this can create stale reads, but the UX patterns around it are often easier to manage than slow, blocking requests.

As traffic grows, strict global agreement can turn coordination into a bottleneck. With eventual consistency, replicas share the workload: read traffic spreads out, and write throughput improves because nodes don’t always wait on cross-region confirmations.

At scale, this is the difference between “add more servers and it gets faster” versus “add more servers and coordination gets harder.”

Constant global coordination can require more expensive infrastructure and careful tuning (think global locks and synchronous replication everywhere). Eventual consistency can lower costs by letting you use more standard replication strategies and fewer “everyone must agree right now” mechanisms.

Fewer coordination requirements can also mean fewer failure modes to debug—making it easier to keep performance predictable as you grow.

Eventual consistency tends to work best when the user can tolerate a small delay between “I did the thing” and “everyone else sees it,” especially when the data is high-volume and not safety‑critical.

Likes, views, follower counts, and post “impressions” are classic examples. If you tap “Like” and the count updates for you immediately, it’s usually fine if another person sees the old number for a few seconds (or even minutes during heavy traffic).

These counters are often updated in batches or through asynchronous processing to keep apps fast. The key is that being off by a small amount rarely changes a user decision in a meaningful way.

Messaging systems often separate delivery receipts (“sent,” “delivered,” “read”) from the actual timing of network delivery. A message might show as “sent” instantly on your phone, while the recipient’s device gets it a moment later due to connectivity, background restrictions, or routing.

Similarly, push notifications can arrive late or out of order, even if the underlying message is already available in the app. Users generally accept this as normal behavior, as long as the app eventually converges and avoids duplicates or missing messages.

Search results and recommendation carousels frequently depend on indexes that refresh after writes. You can publish a product, update a profile, or edit a post and not see it appear in search immediately.

This delay is usually acceptable because users understand search as “updated soon,” not “instantaneously perfect.” The system trades a small freshness gap for faster writes and more scalable searching.

Analytics is often processed on a schedule: every minute, hour, or day. Dashboards may show “last updated at…” because exact real-time numbers are expensive and often unnecessary.

For most teams, it’s fine if a chart lags behind reality—as long as it’s clearly communicated and consistent enough for trends and decisions.

Eventual consistency is a reasonable trade-off when being “a little behind” doesn’t change the outcome. But some features have hard safety requirements: the system must agree now, not later. In these areas, a stale read isn’t just confusing—it can cause real harm.

Payments, transfers, and stored-value balances can’t rely on “it’ll settle soon.” If two replicas temporarily disagree, you risk double-spend scenarios (the same funds used twice) or accidental overdrafts. Users may see a balance that allows a purchase even though the money is already committed elsewhere.

For anything that changes monetary state, teams typically use strong consistency, serializable transactions, or a single authoritative ledger service with strict ordering.

Browsing a catalog can tolerate slightly stale stock counts. Checkout cannot. If the system shows “in stock” based on outdated replicas, you can oversell, then scramble with cancellations, refunds, and support tickets.

A common line is: eventual consistency for product pages, but a confirmed reservation (or atomic decrement) at checkout.

Access control has a short acceptable delay—often effectively zero. If a user’s access is revoked, that revocation must apply immediately. Otherwise you leave a window where someone can still download data, edit settings, or perform admin actions.

This includes password resets, token revocation, role changes, and account suspensions.

Audit trails and compliance records often require strict ordering and immutability. A log that “eventually” reflects an action, or reorders events between regions, can break investigations and regulatory requirements.

In these cases, teams prioritize append-only storage, tamper-evident logs, and consistent timestamps/sequence numbers.

If a temporary mismatch can create irreversible side effects (money moved, goods shipped, access granted, legal record changed), don’t accept eventual consistency for the source of truth. Use it only for derived views—like dashboards, recommendations, or search indexes—where being briefly behind is acceptable.

Eventual consistency doesn’t have to feel “random” to users. The trick is to design the product and APIs so temporary disagreement is expected, visible, and recoverable. When people understand what’s happening—and the system can safely retry—trust goes up even if the data is still catching up behind the scenes.

A small amount of text can prevent a lot of support tickets. Use explicit, friendly status signals like “Saving…”, “Updated just now”, or “May take a moment.”

This works best when the UI distinguishes between:

For example, after changing an address, you might show “Saved—syncing to all devices” rather than pretending the update is instantly everywhere.

Optimistic UI means you show the expected result immediately—because most of the time it will become true. It makes apps feel fast even when replication takes a few seconds.

To keep it reliable:

The key isn’t optimism itself—it’s having a visible “receipt” that arrives shortly after.

With eventual consistency, timeouts and retries are normal. If a user taps “Pay” twice or a mobile app retries a request after losing signal, you don’t want duplicate charges or duplicate orders.

Idempotent actions solve this by making “repeat the same request” produce the same effect. Common approaches include:

This lets you confidently retry without making the user fear that “trying again” is dangerous.

Conflicts occur when two changes happen before the system fully agrees—like two people editing a profile field at the same time.

You generally have three options:

Whatever you choose, make the behavior predictable. Users can tolerate delays; they struggle with surprises.

Eventual consistency is often acceptable—but only if users don’t feel like the app is “forgetting” what they just did. The goal here is simple: align what the user expects to see with what the system can safely guarantee.

If a user edits a profile, posts a comment, or updates an address, the next screen they see should reflect that change. This is the read-your-writes idea: after you write, you should be able to read your own write.

Teams typically implement this by reading from the same place that accepted the write (or by temporarily serving the updated value from a fast cache tied to the user) until replication catches up.

Even if the system can’t make everyone see the update immediately, it can make the same user see a consistent story during their session.

For example, once you “liked” a post, your session shouldn’t flip between liked/unliked just because different replicas are slightly out of sync.

When possible, route a user’s requests to a “known” replica—often the one that handled their recent write. This is sometimes called sticky sessions.

It doesn’t make the database instantly consistent, but it reduces surprising hops between replicas that disagree.

These tactics improve perception and reduce confusion, but they don’t solve every case. If a user logs in on another device, shares a link with someone else, or refreshes after a failover, they may still see older data briefly.

A small amount of product design helps too: show “Saved” confirmations, use optimistic UI carefully, and avoid wording like “Everyone can see this immediately” when that isn’t guaranteed.

Eventual consistency isn’t “set it and forget it.” Teams that rely on it treat consistency as a measurable reliability property: they define what “fresh enough” means, track when reality drifts from that target, and have a plan when the system can’t keep up.

A practical starting point is an SLO for propagation delay—how long it takes for a write in one place to show up everywhere else. Teams often define targets using percentiles (p50/p95/p99) rather than averages, because the long tail is what users notice.

For example: “95% of updates are visible across regions within 2 seconds, 99% within 10 seconds.” Those numbers then guide engineering decisions (batching, retry policies, queue sizing) and product decisions (whether to show a “syncing” indicator).

To keep the system honest, teams continuously log and measure:

These metrics help distinguish normal delay from a deeper problem like a stuck consumer, overloaded queue, or failing network link.

Good alerts focus on patterns that predict user impact:

The goal is to catch “we’re falling behind” before it becomes “users see contradictory states.”

Teams also plan how to degrade gracefully during partitions: temporarily route reads to the “most likely fresh” replica, disable risky multi-step flows, or show a clear status like “Changes may take a moment to appear.” Playbooks make these decisions repeatable under pressure, rather than improvised mid-incident.

Eventual consistency isn’t a “yes or no” choice you make for the whole product. Most successful apps mix models: some actions require instant agreement, while others can safely settle a few seconds later.

A practical way to decide is to ask: what’s the real cost of being briefly wrong?

If a user sees a slightly outdated number of likes, the downside is minor. If they see the wrong account balance, it can trigger panic, support tickets, or worse—financial loss.

When evaluating a feature, run through four questions:

If the answer is “yes” to safety/money/trust, lean toward stronger consistency for that specific operation (or at least for the “commit” step). If reversibility is high and the impact is low, eventual consistency is usually a good trade.

A common pattern is to keep the core transaction strongly consistent, while allowing surrounding features to be eventual:

Once you choose, write it down in plain language: what can be stale, for how long, and what users should expect. This helps product, support, and QA respond consistently (and keeps “it’s a bug” vs “it’ll catch up” from becoming a guessing game). A lightweight internal page—or even a short section in the feature spec—goes a long way.

If you’re moving fast, it also helps to standardize these decisions early. For example, teams using Koder.ai to vibe-code new services often start by describing (in planning mode) which endpoints must be strongly consistent (payments, permissions) versus which can be eventually consistent (feeds, analytics). Having that written contract up front makes it easier to generate the right patterns—like idempotency keys, retry-safe handlers, and clear UI “syncing” states—before you scale.

Eventual consistency isn’t “worse consistency”—it’s a deliberate trade. For many features, it can improve the experience people actually feel: pages load quickly, actions rarely fail, and the app stays available even when parts of the system are under stress. Users typically value “it works and it’s fast” more than “every screen updates everywhere instantly,” as long as the product behaves predictably.

Some categories deserve stricter rules because the cost of being wrong is high. Use strong consistency (or carefully controlled transactions) for:

For everything else—feeds, view counts, search results, analytics, recommendations—eventual consistency is often a sensible default.

The biggest mistakes happen when teams assume consistency behavior without defining it. Be explicit about what “correct” looks like for each feature: acceptable delay, what users should see during that delay, and what happens if updates arrive out of order.

Then measure it. Track real replication delay, stale reads, conflict rates, and user-visible mismatches. Monitoring turns “probably fine” into a controlled, testable decision.

To make this practical, map your product features to their consistency needs, document the choice, and add guardrails:

Consistency isn’t a one-size choice. The goal is a system that’s trustworthy to users—fast where it can be, strict where it must be.

Eventual consistency means different copies of the same data may briefly show different values after an update, but they are designed to converge to the same latest state after updates propagate.

In practice: you might save a change on one screen and see the old value on another for a short time, then it catches up.

Data is often replicated across servers/regions for uptime and speed. Updates have to travel over networks and be applied by multiple replicas.

Because replicas don’t update in perfect lockstep, there’s a window where one replica has the new value and another still has the old one.

“Eventual” is not a fixed number. It depends on replication lag, network latency, load, retries, and outages.

A practical approach is to define a target like:

…and design UX plus monitoring around that.

Strong consistency aims for “everyone agrees now,” which often requires cross-region coordination before a write is confirmed.

That coordination can:

Many systems accept brief disagreement to stay fast and responsive.

The most common user-visible symptoms are:

Good UX makes these feel normal instead of broken.

Read-your-writes means after you change something, your next view should reflect your change even if the rest of the system is still catching up.

Teams often implement it by:

It’s usually fine for high-volume, low-stakes, “derived” experiences where being slightly behind doesn’t cause harm, such as:

The key is that brief inaccuracies rarely change an irreversible decision.

Avoid eventual consistency for the source of truth when a temporary mismatch can cause irreversible harm, including:

You can still use eventual consistency for derived views (e.g., dashboards) fed from a strongly consistent core.

Conflicts happen when two updates occur before replicas agree (e.g., two edits at once). Common strategies are:

Whatever you choose, make the rule predictable and visible when it affects users.

Retries are normal (timeouts, reconnects), so actions must be safe to repeat.

Typical tactics:

This turns “try again” from risky into routine.