Jun 04, 2025·8 min

Why Functional Programming Ideas Keep Returning to Modern Code

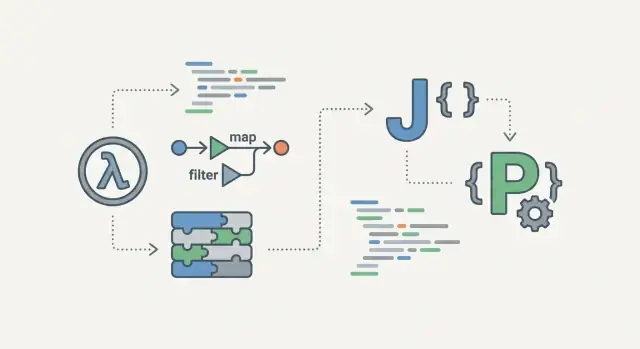

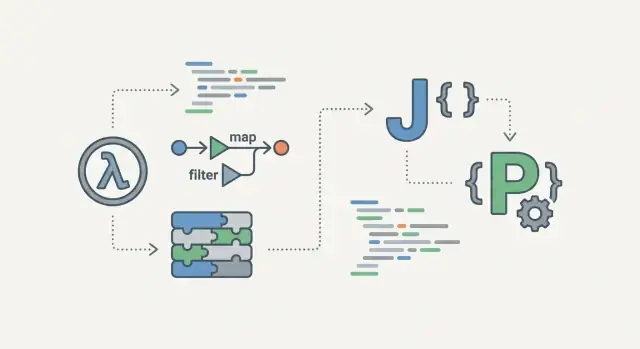

Functional ideas like immutability, pure functions, and map/filter keep showing up in popular languages. Learn why they help and when to use them.

Functional ideas like immutability, pure functions, and map/filter keep showing up in popular languages. Learn why they help and when to use them.

“Functional programming concepts” are simply habits and language features that treat computation like working with values, not constantly changing things.

Instead of writing code that says “do this, then change that,” functional-style code leans toward “take an input, return an output.” The more your functions behave like reliable transformations, the easier it is to predict what the program will do.

When people say Java, Python, JavaScript, C#, or Kotlin are “getting more functional,” they don’t mean these languages are turning into purely functional programming languages.

They mean mainstream language design keeps borrowing useful ideas—like lambdas and higher-order functions—so you can write some parts of your code in a functional style when it helps, and stick with familiar imperative or object-oriented approaches when that’s clearer.

Functional ideas often improve software maintainability by reducing hidden state and making behavior easier to reason about. They can also help with concurrency, because shared mutable state is a major source of race conditions.

The trade-offs are real: extra abstraction can feel unfamiliar, immutability can add overhead in some cases, and “clever” compositions can hurt readability if overdone.

Here’s what “functional concepts” means throughout this article:

These are practical tools, not a doctrine—the goal is to use them where they make code simpler and safer.

Functional programming isn’t a new trend; it’s a set of ideas that resurfaces whenever mainstream development hits a scaling pain point—bigger systems, bigger teams, and new hardware realities.

In the late 1950s and 1960s, languages like Lisp treated functions as real values you could pass around and return—what we now call higher-order functions. That same era also gave us the roots of “lambda” notation: a concise way to describe anonymous functions without naming them.

In the 1970s and 1980s, functional languages such as ML and later Haskell pushed ideas like immutability and strong type-driven design, mostly in academic and niche industrial settings. Meanwhile, many “mainstream” languages quietly borrowed pieces: scripting languages popularized treating functions like data long before enterprise platforms caught up.

In the 2000s and 2010s, functional ideas became hard to ignore:

More recently, languages like Kotlin, Swift, and Rust doubled down on function-based collection tools and safer defaults, while frameworks in many ecosystems encourage pipelines and declarative transformations.

These concepts return because the context keeps changing. When programs were smaller and mostly single-threaded, “just mutate a variable” was often fine. As systems became distributed, concurrent, and maintained by large teams, the cost of hidden coupling increased.

Functional programming patterns—like lambdas, collection pipelines, and explicit async flows—tend to make dependencies visible and behavior more predictable. Language designers keep reintroducing them because they’re practical tools for modern complexity, not museum pieces from computer science history.

Predictable code behaves the same way every time you use it in the same situation. That’s exactly what gets lost when functions quietly depend on hidden state, the current time, global settings, or whatever happened earlier in the program.

When behavior is predictable, debugging becomes less like detective work and more like inspection: you can narrow a problem down to a small piece, reproduce it, and fix it without worrying that the “real” cause is somewhere else.

Most debugging time isn’t spent typing a fix—it’s spent figuring out what the code actually did. Functional programming ideas push you toward behavior you can reason about locally:

That means fewer “it only breaks on Tuesdays” bugs, fewer print statements scattered everywhere, and fewer fixes that accidentally create a new bug two screens away.

A pure function (same input → same output, no side effects) is friendly to unit tests. You don’t need to set up complex environments, mock half your application, or reset global state between test runs. You can also reuse it during refactors because it doesn’t assume where it’s being called from.

This matters in real work:

Before: A function called calculateTotal() reads a global discountRate, checks a global “holiday mode” flag, and updates a global lastTotal. A bug report says totals are “sometimes wrong.” Now you’re chasing state.

After: calculateTotal(items, discountRate, isHoliday) returns a number and changes nothing else. If totals are wrong, you log the inputs once and reproduce the issue immediately.

Predictability is one of the main reasons functional programming features keep getting added to mainstream languages: they make everyday maintenance work less surprising, and surprises are what make software expensive.

A “side effect” is anything a piece of code does besides calculating and returning a value. If a function reads or changes something outside its inputs—files, a database, the current time, global variables, a network call—it’s doing more than just computing.

Everyday examples are everywhere: writing a log line, saving an order to the database, sending an email, updating a cache, reading environment variables, or generating a random number. None of these are “bad,” but they change the world around your program—and that’s where surprises begin.

When effects are mixed into ordinary logic, behavior stops being “data in, data out.” The same inputs can produce different outcomes depending on hidden state (what’s already in the database, which user is logged in, whether a feature flag is on, whether a network request fails). That makes bugs harder to reproduce and fixes harder to trust.

It also complicates debugging. If a function both calculates a discount and writes to the database, you can’t safely call it twice while investigating—because calling it twice might create two records.

Functional programming pushes a simple separation:

With this split, you can test most of your code without a database, without mocking half the world, and without worrying that a “simple” calculation triggers a write.

The most common failure mode is “effect creep”: one function logs “just a little,” then it also reads config, then it also writes a metric, then it also calls a service. Soon, many parts of the codebase depend on hidden behavior.

A good rule of thumb: keep core functions boring—take inputs, return outputs—and make side effects explicit and easy to find.

Immutability is a simple rule with big consequences: don’t change a value—make a new version.

Instead of editing an object “in place,” an immutable approach creates a fresh copy that reflects the update. The old version stays exactly as it was, which makes the program easier to reason about: once a value is created, it won’t unexpectedly change later.

Many everyday bugs come from shared state—the same data being referenced in multiple places. If one part of the code mutates it, other parts may observe a half-updated value or a change they didn’t expect.

With immutability:

This is especially helpful when data is passed widely (configuration, user state, app-wide settings) or used concurrently.

Immutability isn’t free. If implemented poorly, you can pay in memory, performance, or extra copying—for example, repeatedly cloning large arrays inside tight loops.

Most modern languages and libraries reduce these costs with techniques like structural sharing (new versions reuse most of the old structure), but it’s still worth being deliberate.

Prefer immutability when:

Consider controlled mutation when:

A useful compromise is: treat data as immutable at the boundaries (between components) and be selective about mutation inside small, well-contained implementation details.

A big shift in “functional-style” code is treating functions as values. That means you can store a function in a variable, pass it into another function, or return it from a function—just like data.

That flexibility is what makes higher-order functions practical: instead of rewriting the same loop logic over and over, you write the loop once (inside a reusable helper), and plug in the behavior you want via a callback.

If you can pass behavior around, code becomes more modular. You define a small function that describes what should happen to one item, then hand it to a tool that knows how to apply it to every item.

const addTax = (price) => price * 1.2;

const pricesWithTax = prices.map(addTax);

Here, addTax isn’t “called” directly in a loop. It’s passed into map, which handles the iteration.

[a, b, c] → [f(a), f(b), f(c)]predicate(item) is trueconst total = orders

.filter(o => o.status === "paid")

.map(o => o.amount)

.reduce((sum, amount) => sum + amount, 0);

This reads like a pipeline: select paid orders, extract amounts, then add them up.

Traditional loops often mix concerns: iteration, branching, and the business rule all sit in one place. Higher-order functions separate those concerns. The looping and accumulation are standardized, while your code focuses on the “rule” (the small functions you pass in). That tends to reduce copy-pasted loops and one-off variants that drift over time.

Pipelines are great until they become deeply nested or too clever. If you find yourself stacking many transformations or writing long inline callbacks, consider:

Functional building blocks help most when they make intent obvious—not when they turn simple logic into a puzzle.

Modern software rarely runs in a single, quiet thread. Phones juggle UI rendering, network calls, and background work. Servers handle thousands of requests at once. Even laptops and cloud machines ship with multiple CPU cores by default.

When several threads/tasks can change the same data, tiny timing differences create big problems:

These issues aren’t about “bad developers”—they’re a natural outcome of shared mutable state. Locks help, but they add complexity, can deadlock, and often become performance bottlenecks.

Functional programming ideas keep resurfacing because they make parallel work easier to reason about.

If your data is immutable, tasks can share it safely: nobody can change it out from under anyone else. If your functions are pure (same input → same output, no hidden side effects), you can run them in parallel more confidently, cache results, and test them without setting up elaborate environments.

This fits common patterns in modern apps:

Concurrency tools based on FP don’t guarantee a speedup for every workload. Some tasks are inherently sequential, and extra copying or coordination can add overhead.

The main win is correctness: fewer race conditions, clearer boundaries around effects, and programs that behave consistently when run on multi-core CPUs or under real-world server load.

A lot of code is easier to understand when it reads like a series of small, named steps. That’s the core idea behind composition and pipelines: you take simple functions that each do one thing, then connect them so data “flows” through the steps.

Think of a pipeline like an assembly line:

Each step can be tested and changed on its own, and the overall program becomes a readable story: “take this, then do that, then do that.”

Pipelines push you toward functions with clear inputs and outputs. That tends to:

Composition is simply the idea that “a function can be built from other functions.” Some languages offer explicit helpers (like compose), while others rely on chaining (.) or operators.

Here’s a small, pipeline-style example that takes orders, keeps only paid ones, computes totals, and summarizes revenue:

const paid = o => o.status === 'paid';

const withTotal = o => ({ ...o, total: o.items.reduce((s, i) => s + i.price * i.qty, 0) });

const isLarge = o => o.total >= 100;

const revenue = orders

.filter(paid)

.map(withTotal)

.filter(isLarge)

.reduce((sum, o) => sum + o.total, 0);

Even if you don’t know JavaScript well, you can usually read this as: “paid orders → add totals → keep large ones → sum totals.” That’s the big win: the code explains itself by how the steps are arranged.

A lot of “mystery bugs” aren’t about clever algorithms—they’re about data that can silently be wrong. Functional ideas push you to model data so that wrong values are harder (or impossible) to construct, which makes APIs safer and behavior more predictable.

Instead of passing around loosely structured blobs (strings, dictionaries, nullable fields), functional-style modeling encourages explicit types with clear meaning. For example, “EmailAddress” and “UserId” as distinct concepts prevent mixing them up, and validation can happen at the boundary (when data enters your system) rather than scattered across the codebase.

The effect on APIs is immediate: functions can accept already-validated values, so callers can’t “forget” a check. That reduces defensive programming and makes failure modes clearer.

In functional languages, algebraic data types (ADTs) let you define a value as one of a small set of well-defined cases. Think: “a payment is either Card, BankTransfer, or Cash,” each with exactly the fields it needs. Pattern matching is then a structured way to handle each case explicitly.

This leads to the guiding principle: make invalid states unrepresentable. If “Guest users” never have a password, don’t model it as password: string | null; model “Guest” as a separate case that simply has no password field. Many edge cases disappear because the impossible can’t be expressed.

Even without full ADTs, modern languages offer similar tools:

Combined with pattern matching (where available), these features help ensure you handled every case—so new variants don’t become hidden bugs.

Mainstream languages rarely adopt functional programming features because of ideology. They add them because developers keep reaching for the same techniques—and because the rest of the ecosystem rewards those techniques.

Teams want code that’s easier to read, test, and change without unintended ripple effects. As more developers experience benefits like cleaner data transformations and fewer hidden dependencies, they expect those tools everywhere.

Language communities also compete. If one ecosystem makes common tasks feel elegant—say, transforming collections or composing operations—others feel pressure to reduce friction for everyday work.

A lot of “functional style” is driven by libraries rather than textbooks:

Once these libraries become popular, developers want the language to support them more directly: concise lambdas, better type inference, pattern matching, or standard helpers like map, filter, and reduce.

Language features often show up after years of community experimentation. When a certain pattern becomes common—like passing small functions around—languages respond by making that pattern less noisy.

That’s why you often see incremental upgrades rather than sudden “all-in FP”: first lambdas, then nicer generics, then better immutability tools, then improved composition utilities.

Most language designers assume real-world codebases are hybrids. The goal isn’t to force everything into pure functional programming—it’s to let teams use functional ideas where they help:

That middle path is why FP features keep returning: they solve common problems without demanding a full rewrite of how people build software.

Functional programming ideas are most useful when they reduce confusion, not when they become a new style contest. You don’t need to rewrite an entire codebase or adopt a “pure everything” rule to get the benefits.

Begin with low-risk places where functional habits pay off immediately:

If you’re building quickly with an AI-assisted workflow, these boundaries matter even more. For example, on Koder.ai (a vibe-coding platform for generating React apps, Go/PostgreSQL backends, and Flutter mobile apps via chat), you can ask the system to keep business logic in pure functions/modules and isolate I/O in thin “edge” layers. Pair that with snapshots and rollback, and you can iterate on refactors (like introducing immutability or stream pipelines) without betting the whole codebase on one big change.

Functional techniques can be the wrong tool in a few situations:

Agree on shared conventions: where side effects are allowed, how to name pure helpers, and what “immutable enough” means in your language. Use code reviews to reward clarity: prefer straightforward pipelines and descriptive names over dense compositions.

Before you ship, ask:

Used this way, functional ideas become guardrails—helping you write calmer, more maintainable code without turning every file into a philosophy lesson.

Functional concepts are practical habits and features that make code behave more like “input → output” transformations.

In everyday terms, they emphasize:

map, filter, and reduce to transform data clearlyNo. The point is pragmatic adoption, not ideology.

Mainstream languages borrow features (lambdas, streams/sequences, pattern matching, immutability helpers) so you can use functional style where it helps, while still writing imperative or OO code when that’s clearer.

Because they reduce surprises.

When functions don’t rely on hidden state (globals, time, mutable shared objects), behavior becomes easier to reproduce and reason about. That typically means:

A pure function returns the same output for the same input and avoids side effects.

That makes it easy to test: you call it with known inputs and assert the result, without setting up databases, clocks, global flags, or complex mocks. Pure functions also tend to be easier to reuse during refactors because they carry less hidden context.

A side effect is anything a function does beyond returning a value—reading/writing files, calling APIs, writing logs, updating caches, touching globals, using the current time, generating random values, etc.

Effects make behavior harder to reproduce. A practical approach is:

Immutability means you don’t change a value in place; you create a new version instead.

This reduces bugs caused by shared mutable state, especially when data is passed around or used concurrently. It also makes features like caching or undo/redo more natural because older versions remain valid.

Yes—sometimes.

The costs usually show up when you repeatedly copy large structures in tight loops. Practical compromises include:

They replace repetitive loop boilerplate with reusable, readable transformations.

map: transform each elementfilter: keep elements that match a rulereduce: combine many values into oneUsed well, these pipelines make intent obvious (e.g., “paid orders → amounts → sum”) and reduce copy-pasted loop variants.

Because concurrency breaks most often due to shared mutable state.

If data is immutable and your transformations are pure, tasks can safely run in parallel with fewer locks and fewer race conditions. It doesn’t guarantee speedups, but it often improves correctness under load.

Start with small, low-risk wins:

Stop and simplify if the code becomes too clever—name intermediate steps, extract functions, and favor readability over dense compositions.