Jun 04, 2025·8 min

Why Horizontal Scaling Is Harder Than Vertical Scaling

Vertical scaling is often just adding CPU/RAM. Horizontal scaling needs coordination, partitioning, consistency, and more ops work—here’s why it’s harder.

Vertical scaling is often just adding CPU/RAM. Horizontal scaling needs coordination, partitioning, consistency, and more ops work—here’s why it’s harder.

Scaling means “handling more without falling over.” That “more” could be:

When people talk about scaling, they’re usually trying to improve one or more of these:

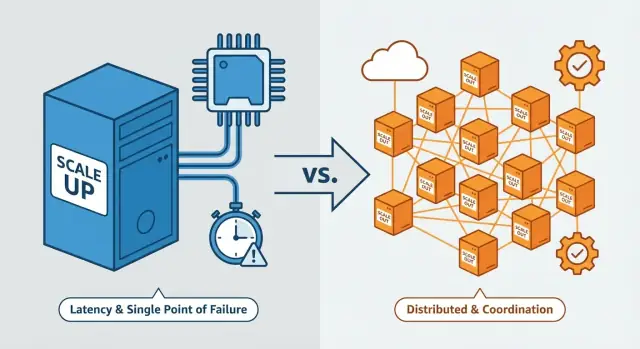

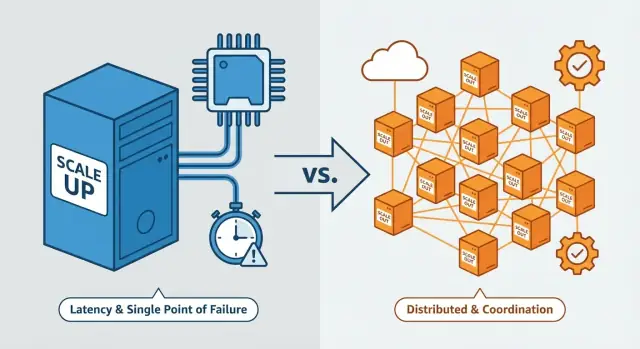

Most of this comes down to a single theme: scaling up preserves a “single system” feel, while scaling out turns your system into a coordinated group of independent machines—and that coordination is where difficulty explodes.

Vertical scaling means making one machine stronger. You keep the same basic architecture, but upgrade the server (or VM): more CPU cores, more RAM, faster disks, higher network throughput.

Think of it like buying a bigger truck: you still have one driver and one vehicle, it just carries more.

Horizontal scaling means adding more machines or instances and splitting work across them—often behind a load balancer. Instead of one stronger server, you run several servers working together.

That’s like using more trucks: you can move more cargo overall, but now you have scheduling, routing, and coordination to worry about.

Common triggers include:

Teams often scale up first because it’s fast (upgrade the box), then scale out when a single machine hits limits or when they need higher availability. Mature architectures commonly mix the two: bigger nodes and more nodes, depending on the bottleneck.

Vertical scaling is appealing because it keeps your system in one place. With a single node, you typically have a single source of truth for memory and local state. One process owns the in-memory cache, the job queue, the session store (if sessions are in memory), and temporary files.

On one server, most operations are straightforward because there’s little or no inter-node coordination:

When you scale up, you pull familiar levers: add CPU/RAM, use faster storage, improve indexes, tune queries and configurations. You don’t have to redesign how data is distributed or how multiple nodes agree on “what happens next.”

Vertical scaling isn’t “free”—it just keeps complexity contained.

Eventually you hit limits: the biggest instance you can rent, diminishing returns, or a steep cost curve at the high end. You may also carry more downtime risk: if the one big machine fails or needs maintenance, a large portion of the system goes with it unless you’ve added redundancy.

When you scale out, you don’t just get “more servers.” You get more independent actors that must agree on who is responsible for each piece of work, at what time, and using which data.

With one machine, coordination is often implicit: one memory space, one process, one place to look for state. With many machines, coordination becomes a feature you have to design.

Common tools and patterns include:

Coordination bugs rarely look like clean crashes. More often you see:

These issues often show up only under real load, during deployments, or when partial failures occur (one node is slow, a switch drops packets, a single zone blips). The system looks fine—until it’s stressed.

When you scale out, you often can’t keep all your data in one place. You split it across machines (shards) so multiple nodes can store and serve requests in parallel. That split is where complexity starts: every read and write depends on “which shard holds this record?”

Range partitioning groups data by an ordered key (for example, users A–F on shard 1, G–M on shard 2). It’s intuitive and supports range queries well (“show orders from last week”). The downside is uneven load: if one range gets popular, that shard becomes a bottleneck.

Hash partitioning runs a key through a hash function and distributes results across shards. It spreads traffic more evenly, but makes range queries harder because related records are scattered.

Add a node and you want to use it—meaning some data must move. Remove a node (planned or due to failure) and other shards must take over. Rebalancing can trigger large transfers, cache warm-ups, and temporary performance drops. During the move, you also need to prevent stale reads and misrouted writes.

Even with hashing, real traffic isn’t uniform. A celebrity account, a popular product, or time-based access patterns can concentrate reads/writes on one shard. One hot shard can cap the throughput of the entire system.

Sharding introduces ongoing responsibilities: maintaining routing rules, running migrations, performing backfills after schema changes, and planning splits/merges without breaking clients.

When you scale out, you don’t just add more servers—you add more copies of your application. The hard part is state: anything your app “remembers” between requests or while work is in progress.

If a user logs in on Server A but their next request lands on Server B, does B know who they are?

Caches speed things up, but multiple servers mean multiple caches. Now you deal with:

With many workers, background jobs can run twice unless you design for it. You typically need a queue, leases/locks, or idempotent job logic so “send invoice” or “charge card” doesn’t happen twice—especially during retries and restarts.

With a single node (or a single primary database), there’s usually a clear “source of truth.” When you scale out, data and requests spread across machines, and keeping everyone in sync becomes a constant concern.

Eventual consistency is often faster and cheaper at scale, but it introduces surprising edge cases.

Common issues include:

You can’t eliminate failures, but you can design for them:

A transaction across services (order + inventory + payment) requires multiple systems to agree. If one step fails mid-way, you need compensating actions and careful bookkeeping. Classic “all-or-nothing” behavior is hard when networks and nodes fail independently.

Use strong consistency for things that must be correct: payments, account balances, inventory counts, seat reservations. For less critical data (analytics, recommendations), eventual consistency is often acceptable.

When you scale up, many “calls” are function calls in the same process: fast and predictable. When you scale out, the same interaction becomes a network call—adding latency, jitter, and failure modes your code must handle.

Network calls have fixed overhead (serialization, queuing, hops) and variable overhead (congestion, routing, noisy neighbors). Even if average latency is fine, tail latency (the slowest 1–5%) can dominate user experience because a single slow dependency stalls the whole request.

Bandwidth and packet loss also become constraints: at high request rates, “small” payloads add up, and retransmits quietly increase load.

Without timeouts, slow calls pile up and threads get stuck. With timeouts and retries, you can recover—until retries amplify load.

A common failure pattern is a retry storm: a backend slows down, clients time out and retry, retries increase load, and the backend gets even slower.

Safer retries usually require:

With multiple instances, clients need to know where to send requests—via a load balancer or service discovery plus client-side balancing. Either way, you add moving parts: health checks, connection draining, uneven traffic distribution, and the risk of routing to a half-broken instance.

To prevent overload from spreading, you need backpressure: bounded queues, circuit breakers, and rate limiting. The goal is to fail fast and predictably instead of letting a small slowdown turn into a system-wide incident.

Vertical scaling tends to fail in a straightforward way: one bigger machine is still a single point. If it slows down or crashes, the impact is obvious.

Horizontal scaling changes the math. With many nodes, it’s normal for some machines to be unhealthy while others are fine. The system is “up,” but users still see errors, slow pages, or inconsistent behavior. This is partial failure, and it becomes the default state you design for.

In a scaled-out setup, services depend on other services: databases, caches, queues, downstream APIs. A small issue can ripple:

To survive partial failures, systems add redundancy:

This increases availability, but introduces edge cases: split-brain scenarios, stale replicas, and decisions about what to do when quorum can’t be reached.

Common patterns include:

With a single machine, the “system story” lives in one place: one set of logs, one CPU graph, one process to inspect. With horizontal scaling, the story is scattered.

Every additional node adds another stream of logs, metrics, and traces. The hard part isn’t collecting data—it’s correlating it. A checkout error might start on a web node, call two services, hit a cache, and read from a specific shard, leaving clues in different places and timelines.

Problems also become selective: one node has a bad config, one shard is hot, one zone has higher latency. Debugging can feel random because it “works fine” most of the time.

Distributed tracing is like attaching a tracking number to a request. A correlation ID is that tracking number. You pass it through services and include it in logs so you can pull one ID and see the full journey end-to-end.

More components usually means more alerts. Without tuning, teams get alert fatigue. Aim for actionable alerts that clarify:

Capacity issues often appear before failures. Monitor saturation signals such as CPU, memory, queue depth, and connection pool usage. If saturation appears on only a subset of nodes, suspect balancing, sharding, or configuration drift—not just “more traffic.”

When you scale out, a deploy is no longer “replace one box.” It’s coordinating changes across many machines while keeping the service available.

Horizontal deployments often use rolling updates (replace nodes gradually), canaries (send a small percentage of traffic to the new version), or blue/green (switch traffic between two full environments). They reduce blast radius, but add requirements: traffic shifting, health checks, draining connections, and a definition of “good enough to proceed.”

During any gradual deploy, old and new versions run side-by-side. That version skew means your system must tolerate mixed behavior:

APIs need backward/forward compatibility, not just correctness. Database schema changes should be additive when possible (add nullable columns before making them required). Message formats should be versioned so consumers can read both old and new events.

Rolling back code is easy; rolling back data is not. If a migration drops or rewrites fields, older code may crash or silently mis-handle records. “Expand/contract” migrations help: deploy code that supports both schemas, migrate data, then remove old paths later.

With many nodes, configuration management becomes part of the deploy. A single node with stale config, wrong feature flags, or expired credentials can create flaky, hard-to-reproduce failures.

Horizontal scaling can look cheaper on paper: lots of small instances, each with a low hourly price. But the total cost isn’t just compute. Adding nodes also means more networking, more monitoring, more coordination, and more time spent keeping things consistent.

Vertical scaling concentrates spend into fewer machines—often fewer hosts to patch, fewer agents to run, fewer logs to ship, fewer metrics to scrape.

With scale out, the per-unit price may be lower, but you often pay for:

To handle spikes safely, distributed systems frequently run under-full. You keep headroom on multiple tiers (web, workers, databases, caches), which can mean paying for idle capacity across dozens or hundreds of instances.

Scale out increases on-call load and demands mature tooling: alert tuning, runbooks, incident drills, and training. Teams also spend time on ownership boundaries (who owns which service?) and incident coordination.

The result: “cheaper per unit” can still be more expensive overall once you include people time, operational risk, and the work required to make many machines behave like one system.

Choosing between scaling up (bigger machine) and scaling out (more machines) isn’t just about price. It’s about workload shape and how much operational complexity your team can absorb.

Start with the workload:

A common, sensible path:

Many teams keep the database vertical (or lightly clustered) while scaling the stateless app tier horizontally. This limits sharding pain while still letting you add web capacity quickly.

You’re closer when you have solid monitoring and alerts, tested failover, load tests, and repeatable deployments with safe rollbacks.

A lot of scaling pain isn’t just “architecture”—it’s the operational loop: iterating safely, deploying reliably, and rolling back fast when reality disagrees with your plan.

If you’re building web, backend, or mobile systems and want to move quickly without losing control, Koder.ai can help you prototype and ship faster while you make these scale decisions. It’s a vibe-coding platform where you build applications through chat, with an agent-based architecture under the hood. In practice that means you can:

Because Koder.ai runs globally on AWS, it can also support deployments in different regions to meet latency and data-transfer constraints—useful once multi-zone or multi-region availability becomes part of your scaling story.

Vertical scaling means making a single machine bigger (more CPU/RAM/faster disk). Horizontal scaling means adding more machines and spreading work across them.

Vertical often feels simpler because your app still behaves like “one system,” while horizontal requires multiple systems to coordinate and stay consistent.

Because the moment you have multiple nodes, you need explicit coordination:

A single machine avoids many of these distributed-system problems by default.

It’s the time and logic spent making multiple machines behave like one:

Even if each node is simple, the system behavior gets harder to reason about under load and failure.

Sharding (partitioning) splits data across nodes so no single machine has to store/serve everything. It’s hard because you must:

It also increases operational work (migrations, backfills, shard maps).

State is anything your app “remembers” between requests or while work is in progress (sessions, in-memory caches, temporary files, job progress).

With horizontal scaling, requests may land on different servers, so you typically need shared state (e.g., Redis/db) or you accept trade-offs like sticky sessions.

If multiple workers can pick up the same job (or a job is retried), you can end up charging twice or sending duplicate emails.

Common mitigations:

Strong consistency means once a write succeeds, all readers immediately see it. Eventual consistency means updates propagate over time, so some readers may see stale data briefly.

Use strong consistency for correctness-critical data (payments, balances, inventory). Use eventual consistency where small delays are acceptable (analytics, recommendations).

In a distributed system, calls become network calls, which adds latency, jitter, and failure modes.

Basics that usually matter most:

Partial failure means some components are broken or slow while others are fine. The system can be “up” but still produce errors, timeouts, or inconsistent behavior.

Design responses include replication, quorums, multi-zone deployments, circuit breakers, and graceful degradation so failures don’t cascade.

Across many machines, evidence is fragmented: logs, metrics, and traces live on different nodes.

Practical steps: