Aug 04, 2025·8 min

Why Many Startups Should Skip VC and Win Bootstrapped

Venture capital isn’t right for many startups. Learn when to avoid VC, what bootstrapped companies do differently, and how to win with customer-funded growth.

Venture capital isn’t right for many startups. Learn when to avoid VC, what bootstrapped companies do differently, and how to win with customer-funded growth.

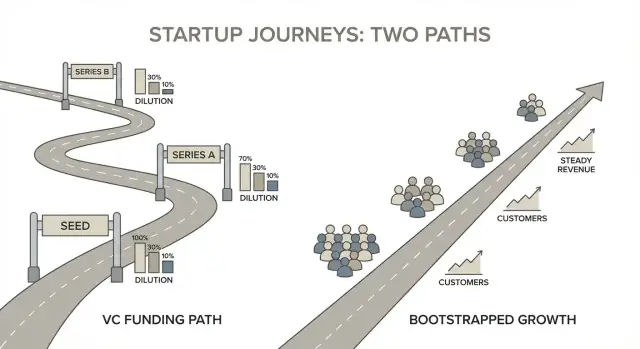

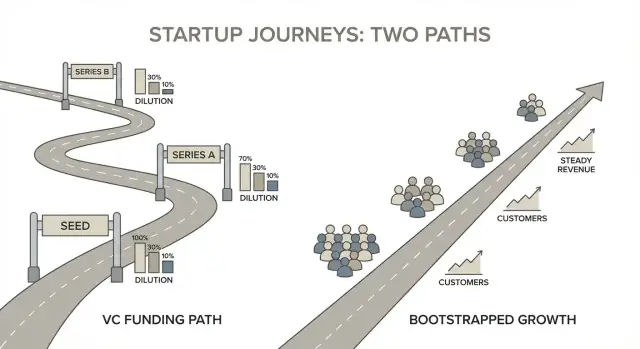

Most funding advice treats venture capital (VC) like a milestone: raise a round, hire fast, “scale.” But VC isn’t a trophy—it’s a specific trade.

VC is professional investment money you take in exchange for equity (ownership). In return, investors expect you to pursue a growth path big enough to produce an outlier outcome—typically a large acquisition or IPO.

That expectation shapes almost every decision afterward: how quickly you hire, how aggressively you spend, what market you target, and how soon you need evidence that the business can become very large.

Bootstrapping means building the business using revenue from customers, founder savings, or smaller, more flexible capital (like a modest loan). Instead of optimizing for the fastest possible growth, you’re optimizing for survival, learning, and steady improvement—often aiming for profitability earlier.

Bootstrapping doesn’t mean “small” or “slow.” It means you keep more control over pace, priorities, and outcomes because you’re not committed to a venture-style return timeline.

The goal is not to persuade you that one path is morally superior. It’s to help you choose the funding approach that matches your business model, your market, and what you actually want as a founder.

Some startups are genuinely venture-backable and benefit from VC. Many others can build a valuable company—with less stress and more optionality—by staying customer-funded.

There’s no universal “best” option—only best fit, given your product, growth ceiling, and tolerance for dilution, pressure, and loss of control.

Venture capital isn’t “bad.” It’s built for a very specific kind of business. VC funds need a small number of investments to return the entire fund, which means they’re hunting for outlier outcomes—companies that can plausibly become huge.

If your startup can become a great, profitable business without becoming a category-dominating giant, VC may push you toward a game you don’t actually want to play.

To meet investor expectations, founders often accept growth targets that are not just ambitious, but structurally aggressive. That can lead to premature scaling: hiring ahead of demand, expanding into new markets too early, or building features for an imagined enterprise buyer instead of serving the customers who are already paying.

The business can end up optimized for the next funding round rather than for durable customer value.

Raising VC almost always means selling meaningful ownership. Over time, dilution can shift how decisions get made and what “success” looks like.

Common side effects include:

Even when investors are supportive, the incentives are different: funds are rewarded for big exits, not steady, profitable growth.

Fundraising is more than pitch meetings. It’s prep work, financial modeling, follow-ups, partner meetings, legal negotiations, and then ongoing investor updates. That time comes from somewhere—usually customer research, sales, support, and product iteration.

If your advantage is speed, focus, and closeness to customers, a long fundraising cycle can be an expensive trade.

VC can be right when the market demands huge upfront spend and the upside is massive. But for many startups, it’s simply a mismatch between the business you can realistically build and the outcome the capital requires.

Venture capital isn’t “good money” or “bad money”—it’s a tool designed for a specific outcome: a small number of outsized winners returning the whole fund. To decide if VC fits, run your startup through four practical filters.

Ask whether your market can realistically support a company worth hundreds of millions (or more), not just a healthy, profitable business. A niche can be excellent for bootstrapping—high customer value, low competition, and steady demand—but it may not produce the kind of exit VC requires.

A quick check: if you captured a meaningful share of your best customers, would the result be “life-changing for a fund,” or “a great founder business”?

VC-backed companies are expected to grow aggressively. The question isn’t whether you want to grow fast, but whether fast growth is operationally safe.

If onboarding, support, implementation, compliance, or hiring can’t keep up, rushing can create churn, reputation damage, and a fragile culture. If your product needs deep iteration with early customers, slower growth might be a feature—not a bug.

Venture-scale growth usually depends on strong gross margins and fast payback on customer acquisition. If you spend $1 to acquire a customer, how quickly do you earn it back—and how confidently can you reinvest?

If margins are thin, sales cycles are long, or churn is hard to predict, raising VC can amplify pressure without solving the underlying economics.

VC works best when there’s a repeatable way to acquire customers: a clear channel, a predictable funnel, and scalable messaging.

If your go-to-market depends on founder networks, bespoke enterprise deals, or slow trust-building, that can still be a great business—but it often scales in years, not quarters.

If you’re unsure, treat these filters as hypotheses to test over the next 60–90 days before taking capital that will set your pace for you.

VC money rarely just “accelerates” what you were already going to do. It usually changes the game you’re playing. Once your timeline is tied to the next round, growth stops being one priority among many and becomes the priority that everything else serves.

The fastest path to bigger numbers often isn’t the best path to a durable business.

Under VC pressure, it’s common to chase larger logos, broader markets, or trendier use cases because they sound like a bigger outcome. But that shift can pull you away from the customer segment that actually loves your product and pays reliably.

Instead of deepening product-market fit in one clear niche, you end up with a blur of “we can serve everyone,” which usually means you serve no one especially well.

Headcount is the easiest lever to pull when growth is the headline goal. A bigger team feels like progress—until your monthly burn forces decisions you wouldn’t otherwise make.

When you hire ahead of proven demand, the business model starts to revolve around maintaining the team:

That burn then “requires” another round, which increases the pressure cycle.

To hit adoption targets, startups often slide into free plans, steep discounts, or custom pricing that’s hard to raise later. It can look great in a dashboard—more users, more logos—but it teaches the market the wrong lesson: that your product is cheap, optional, or easy to replace.

Value-based pricing takes patience and clarity. VC timelines can punish both.

A subtle shift happens when the main audience becomes investors rather than customers. Roadmaps start optimizing for narrative:

The result is a product that is easier to pitch than to use.

If you want to see the alternative path, the next section on /blog/the-hidden-costs-dilution-control-and-incentives digs into why these incentives are so sticky once they start.

Raising venture capital doesn’t just add cash—it rewrites ownership, decision rights, and what “success” looks like.

A simple cap table example makes this real. Suppose two founders start with 50/50.

Nothing “bad” happened—and yet each founder went from 50% to 34% before Series A. If you raise multiple rounds, dilution can compound quickly.

VC money often comes with governance. Once you have an investor on the board (or strong protective provisions), certain decisions may require approval, such as:

Even if you’re still “in charge,” you may need consensus to move.

Many VC deals include liquidation preferences (often 1x, sometimes with participation) and other terms that create a “preference stack.” In some exits, investors get their money back first—sometimes plus extra—before common shareholders (founders/employees) see proceeds. Two companies can sell for the same price and produce very different founder outcomes depending on the stack.

VC can increase pressure on founders: higher burn, higher expectations, and less freedom to keep salary stable. That can create runway anxiety and reduce career optionality—because the plan may require a big outcome on a fixed timeline.

Bootstrapping usually trades speed for resilience: more control over pace, product direction, and what “enough” looks like.

Bootstrapped startups don’t win by telling the best funding story—they win by building a revenue engine early. That changes what “progress” looks like. Instead of chasing the biggest possible market narrative, bootstrapped founders tend to prioritize a business model that starts paying for itself quickly and gets stronger month after month.

When you’re not optimizing for fundraising, you stop designing the company around what investors want to hear. You design it around what customers will pay for—now.

That usually means:

The goal isn’t to look impressive on a pitch deck. The goal is to make the next sale easier than the last.

Bootstrapped companies often choose customers differently. They look for buyers who have budget, feel the pain today, and can decide quickly. Early revenue does more than fund growth—it validates that you’re solving a problem worth paying for.

Retention matters even more under bootstrapping. If customers don’t stick around, you don’t just lose growth—you lose oxygen. So bootstrapped teams tend to build:

Bootstrapping forces a simple loop: ship something useful, charge for it, learn from real behavior, and iterate. There’s less room for “free traction” that doesn’t translate to revenue.

Because the feedback is tied to payment and retention, it’s clearer. You find out quickly whether:

Capital efficiency isn’t only about spending less—it’s about getting more output per dollar and per hour. Bootstrapped teams often build habits that compound: smaller experiments, disciplined hiring, and marketing channels that pay back quickly.

Over time, this becomes a competitive edge: you can grow steadily without needing perfect timing, constant fundraising, or permission to keep going.

Customer-funded growth is simple: you let real buyers pay for the work that moves the business forward. It’s not “growth at any cost.” It’s growth that stays honest—because revenue, churn, and renewals quickly reveal what’s working.

Bootstrapped companies win by being specific. Choose an ideal customer profile (ICP) you can reach quickly and understand deeply, then focus on a problem that already has budget attached.

A useful test: can your target buyer describe the pain in one sentence and explain what it costs them each month in lost time, missed revenue, compliance risk, or headcount? If not, it’s probably too vague to fund your early build.

Instead of spending months building a “complete product,” sell a small, clear engagement:

This creates urgency, keeps scope controlled, and gives you real usage data—not opinions.

Bootstrapping breaks when pricing is built on “we’ll monetize later.” Price so the business can support delivery, support, and continued development now.

A practical starting point: price around the customer’s cost of the problem (or the savings you create), and make sure the first deal can contribute meaningfully to payroll and tooling after direct costs.

When cash is your fuel, your roadmap should be tied to outcomes:

If a feature doesn’t help customers stay, share, or buy more, it’s a “later” item—no matter how exciting it sounds.

One underrated bootstrapping advantage is shortening the build–sell–learn loop without inflating headcount. For example, teams use Koder.ai (a vibe-coding platform) to go from a product idea to working web, backend, or mobile prototypes through a chat interface—then iterate quickly with customers.

If you’re trying to stay lean, features like planning mode, source code export, built-in hosting/deployment, custom domains, and snapshots/rollback can reduce both engineering overhead and “tool sprawl,” while keeping you in control of the codebase as the product matures.

Bootstrapped companies don’t “run on runway” the same way VC-backed startups do. Your operating model has one job: keep the business alive long enough to learn, ship, and sell—without forcing a fundraising timeline.

Start by defining an explicit monthly burn limit (or a break-even deadline) that you refuse to cross. Treat it as a design constraint, not a spreadsheet output.

Instead of planning around a future round, plan around profitability milestones: “We reach cash-flow break-even at X MRR,” or “We can fund one more hire once we sustain Y gross margin for Z months.” This keeps decisions grounded in what the business can actually afford.

Cash flow is something you can engineer. A few tactics reliably extend runway without starving growth:

These moves reduce dependency on external capital while validating demand early.

If you spend money to acquire customers, keep the payback period short whenever possible. A shorter payback means your growth “recycles” cash faster, which is the bootstrapped advantage.

Even simple discipline helps: cap acquisition spend until you can confidently measure payback, and prefer channels where you can pause spend without breaking growth.

Fixed costs create fragile companies. Keep the team lean, outsource selectively (especially for design, specialized engineering, or one-time projects), and audit tool spend every quarter. Small recurring costs compound into real burn—often without improving customer value.

Capital efficiency isn’t about being cheap. It’s about buying time and focus, so customers—not investors—fund the next step.

Bootstrapping changes what “winning” looks like. When you’re not optimizing for the next round, your goals can be built around durability: staying in control, serving customers well, and growing at a pace that doesn’t break the team or the product.

Start by writing down what you actually want to optimize for—because bootstrapping gives you more choices than “grow at all costs.” For many founders, success is a mix of:

Once those priorities are explicit, it becomes easier to pick metrics that reinforce them.

Bootstrapped companies benefit from measurement that reflects customer love and financial stability, not just top-line growth.

Focus on:

A simple rule: if a metric can look great while customers quietly leave or cash quietly shrinks, it’s not a primary metric.

Choose growth targets that you can fund through customer revenue without eroding quality—e.g., “20% quarter-over-quarter while maintaining churn under X% and support response times under Y.” The goal is compounding, not spikes that create refunds, burnout, or a product full of shortcuts.

Consistency beats intensity.

Over time, these habits turn your strategy into a system: cash funds growth, and quality protects cash.

VC isn’t the only way to access capital—and for many founders, it’s not even the best way. The goal isn’t to “never raise money.” It’s to raise the right kind of money, in the right amount, for a specific purpose that improves the business.

Angels (founder-aligned individuals). Angel checks can help you reach an inflection point—like shipping a v1, hiring a key role, or validating a go-to-market channel—without locking you into a VC timeline. Look for angels who value profitability and sustainable growth, not just “hypergrowth.”

Revenue-based financing (RBF). RBF can work well when you have predictable revenue and clear unit economics. You repay as a percentage of revenue, so payments flex with performance. It’s best used to scale something already working (like a paid acquisition channel), not to “find product-market fit.”

Bank loans and lines of credit. For stable businesses, debt is often simpler than equity. It’s typically cheaper than dilution, but it requires discipline: you need reliable cash flow and a plan for repayment. A credit line can also smooth working capital needs (inventory, receivables) without changing ownership.

Grants. If you qualify, grants are non-dilutive and can fund R&D, hiring, or pilots. The tradeoff is time and paperwork—treat them as a bonus, not your only plan.

Crowdfunding (rewards or equity). Crowdfunding can double as marketing and validation, especially for consumer products. Equity crowdfunding can raise meaningful capital, but it creates a large cap table—make sure you’re comfortable with the operational overhead.

Whatever the source, tie capital to a concrete project with measurable outcomes: “$150k to finance inventory for Q4,” or “$80k to hire a salesperson and prove repeatable outbound.” If the purpose is “extend runway,” you’re often just paying to delay hard decisions.

Negotiate for clarity. Avoid complex terms you don’t understand, and push for plain-language explanations in writing. Many bootstrapped companies benefit from small capital that accelerates a proven motion without forcing VC-style growth targets or giving up control.

You don’t need a perfect prediction of the future—you need a repeatable way to decide what kind of company you’re building and what kind of financing matches it.

Keep it brutally simple and written (not a mental model). One page forces clarity.

Include four headings:

If you can’t write this memo convincingly, you’re not ready to fundraise—and you may be describing a great bootstrapped company.

Treat this as a proof-of-traction experiment. Set one measurable goal (e.g., first 10 paying customers, first $1k MRR, churn below X%). In 90 days you’ll learn more than in 20 coffee chats with investors.

Use the sprint to validate:

Decide your non-negotiables before you’re negotiating.

Write these down so you don’t “accidentally” build a burn rate that forces another round.

Make the path concrete: first $1k / $10k / $100k MRR (or equivalent). For each milestone, define:

The next step is choosing: do you want the company that wins by speed and scale, or the one that wins by focus, cash flow, and control?

VC is equity financing from professional investors who expect an outlier outcome (typically a large acquisition or IPO). That expectation usually implies aggressive growth, a push toward venture-scale markets, and decisions optimized for future rounds and exit timelines—not just for profitability.

Bootstrapping means funding the company primarily through customer revenue, founder savings, or small flexible capital (e.g., modest loans). The trade is usually slower, steadier growth in exchange for more control, earlier focus on profitability, and fewer incentives to chase a venture-style exit.

Many startups are great businesses but not great VC bets. Common mismatches include:

Use four filters:

VC pressure often changes who you build for and why:

If you want a deeper look at these incentive shifts, see /blog/the-hidden-costs-dilution-control-and-incentives.

Dilution reduces your ownership percentage as new shares are issued (option pools + rounds). A typical early sequence can move founders from 50% each to something like ~34% each after an option pool and a Seed round.

Practically, dilution can change incentives (what “success” means) and can compound over multiple rounds.

VC often comes with governance rights (board seats and protective provisions). That can mean certain actions require approval, such as:

You may still run the company day-to-day, but you can lose unilateral decision-making.

Bootstrapped companies tend to win by building a revenue engine early:

Progress is measured less by “traction stories” and more by renewals, margins, and cash flow.

Start with a simple paid offer that creates urgency and limits scope:

The goal is to collect real usage and payment signals early, then automate what customers repeatedly buy.

Consider options that preserve flexibility:

If multiple answers are “no,” treat VC as unlikely to be a good fit right now.

Whatever you choose, tie funding to a specific project with measurable outcomes, not “extend runway.”