Sep 08, 2025·8 min

Why Native Frameworks Still Matter for High-Performance Apps

Native frameworks still win for low-latency, smooth UI, battery efficiency, and deep hardware access. Learn when native beats cross-platform.

Native frameworks still win for low-latency, smooth UI, battery efficiency, and deep hardware access. Learn when native beats cross-platform.

“Performance-critical” doesn’t mean “nice to have fast.” It means the experience breaks down when the app is even slightly slow, inconsistent, or delayed. Users don’t just notice the lag—they lose trust, miss a moment, or make mistakes.

A few common app types make this easy to see:

In all of these, performance isn’t a hidden technical metric. It’s visible, felt, and judged within seconds.

When we say native frameworks, we mean building with the tools that are first-class on each platform:

Native doesn’t automatically mean “better engineering.” It means your app is speaking the platform’s language directly—especially important when you’re pushing the device hard.

Cross-platform frameworks can be a great choice for many products, particularly when speed of development and shared code matter more than squeezing every millisecond.

This article isn’t arguing “native always.” It’s arguing that when an app is truly performance-critical, native frameworks often remove whole categories of overhead and limitations.

We’ll evaluate performance-critical needs across a few practical dimensions:

These are the areas where users feel the difference—and where native frameworks tend to shine.

Cross-platform frameworks can feel “close enough” to native when you’re building typical screens, forms, and network-driven flows. The difference usually appears when an app is sensitive to small delays, needs consistent frame pacing, or has to push the device hard for long sessions.

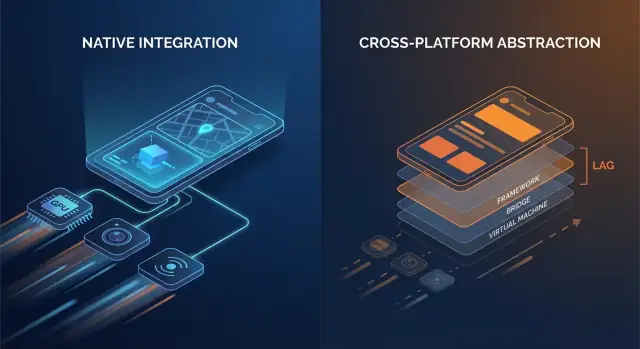

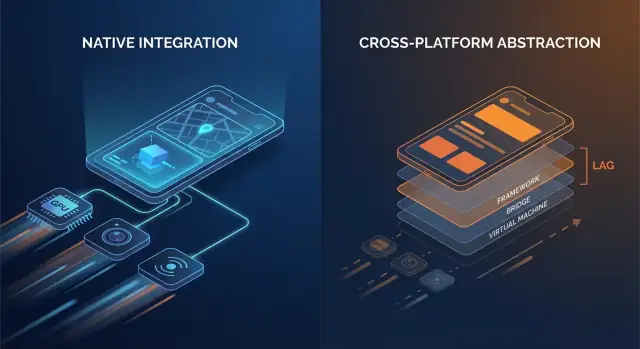

Native code generally talks to OS APIs directly. Many cross-platform stacks add one or more translation layers between your app logic and what the phone ultimately renders.

Common overhead points include:

None of these costs is huge in isolation. The issue is repetition: they can appear on every gesture, every animation tick, and every list item.

Overhead isn’t only about raw speed; it’s also about when work happens.

Native apps can also hit these issues—but there are fewer moving parts, which means fewer places where surprises can hide.

Think: fewer layers = fewer surprises. Each added layer can be well engineered, but it still introduces more scheduling complexity, more memory pressure, and more translation work.

For many apps, the overhead is acceptable and the productivity win is real. But for performance-critical apps—fast-scrolling feeds, heavy animations, real-time collaboration, audio/video processing, or anything latency-sensitive—those “small” costs can become user-visible quickly.

Smooth UI isn’t just a “nice-to-have”—it’s a direct signal of quality. On a 60 Hz screen, your app has about 16.7 ms to produce each frame. On 120 Hz devices, that budget drops to 8.3 ms. When you miss that window, the user sees it as stutter (jank): scrolling that “catches,” transitions that hitch, or a gesture that feels slightly behind their finger.

People don’t consciously count frames, but they do notice inconsistency. A single dropped frame during a slow fade might be tolerable; a few dropped frames during a fast scroll is immediately obvious. High refresh rate screens also raise expectations—once users experience 120 Hz smoothness, inconsistent rendering feels worse than it did on 60 Hz.

Most UI frameworks still rely on a primary/UI thread to coordinate input handling, layout, and drawing. Jank often appears when that thread does too much work within one frame:

Native frameworks tend to have well-optimized pipelines and clearer best practices for keeping work off the main thread, minimizing layout invalidations, and using GPU-friendly animations.

A key difference is the rendering path:

Complex lists are the classic stress test: fast scrolling + image loading + dynamic cell heights can create layout churn and GC/memory pressure.

Transitions can reveal pipeline inefficiencies: shared-element animations, blurred backdrops, and layered shadows are visually rich but can spike GPU cost and overdraw.

Gesture-heavy screens (drag-to-reorder, swipe cards, scrubbers) are unforgiving because the UI must respond continuously. When frames arrive late, the UI stops feeling “attached” to the user’s finger—which is exactly what high-performance apps avoid.

Latency is the time between a user action and the app’s response. Not overall “speed,” but the gap you feel when you tap a button, type a character, drag a slider, draw a stroke, or play a note.

Useful rule-of-thumb thresholds:

Performance-critical apps—messaging, note-taking, trading, navigation, creative tools—live and die by these gaps.

Most app frameworks handle input on one thread, run app logic somewhere else, and then ask the UI to update. When that path is long or inconsistent, latency spikes.

Cross-platform layers can add extra steps:

Each handoff (a “thread hop”) adds overhead and, more importantly, jitter—the response time varies, which often feels worse than a steady delay.

Native frameworks tend to have a shorter, more predictable path from touch → UI update because they align closely with the OS scheduler, input system, and rendering pipeline.

Some scenarios have hard limits:

Native-first implementations make it easier to keep the “critical path” short—prioritizing input and rendering over background work—so real-time interactions stay tight and trustworthy.

Performance isn’t only about CPU speed or frame rate. For many apps, the make-or-break moments happen at the edges—where your code touches the camera, sensors, radios, and OS-level services. Those capabilities are designed and shipped as native APIs first, and that reality shapes what’s feasible (and how stable it is) in cross-platform stacks.

Features like camera pipelines, AR, BLE, NFC, and motion sensors often require tight integration with device-specific frameworks. Cross-platform wrappers can cover the common cases, but advanced scenarios tend to expose gaps.

Examples where native APIs matter:

When iOS or Android ships new features, official APIs are immediately available in native SDKs. Cross-platform layers may need weeks (or longer) to add bindings, update plugins, and work through edge cases.

That lag isn’t just inconvenient—it can create reliability risk. If a wrapper hasn’t been updated for a new OS release, you may see:

For performance-critical apps, native frameworks reduce the “waiting on the wrapper” problem and let teams adopt new OS capabilities on day one—often the difference between a feature shipping this quarter or next.

Speed in a quick demo is only half the story. The performance users remember is the kind that holds up after 20 minutes of use—when the phone is warm, the battery is dropping, and the app has been in the background a few times.

Most “mysterious” battery drains are self-inflicted:

Native frameworks typically offer clearer, more predictable tools to schedule work efficiently (background tasks, job scheduling, OS-managed refresh), so you can do less work overall—and do it at better times.

Memory doesn’t just affect whether an app crashes—it affects smoothness.

Many cross-platform stacks rely on a managed runtime with garbage collection (GC). When memory builds up, GC may pause the app briefly to clean up unused objects. You don’t need to understand the internals to feel it: occasional micro-freezes during scrolling, typing, or transitions.

Native apps tend to follow platform patterns (like ARC-style automatic reference counting on Apple platforms), which often spreads cleanup work more evenly. The result can be fewer “surprise” pauses—especially under tight memory conditions.

Heat is performance. As devices warm up, the OS may throttle CPU/GPU speeds to protect hardware, and frame rates drop. This is common in sustained workloads like games, turn-by-turn navigation, camera + filters, or real-time audio.

Native code can be more power-efficient in these scenarios because it can use hardware-accelerated, OS-tuned APIs for heavy tasks—such as native video playback pipelines, efficient sensor sampling, and platform media codecs—reducing wasted work that turns into heat.

When “fast” also means “cool and steady,” native frameworks often have an edge.

Performance work succeeds or fails on visibility. Native frameworks usually ship with the deepest hooks into the operating system, the runtime, and the rendering pipeline—because they’re built by the same vendors who define those layers.

Native apps can attach profilers at the boundaries where delays are introduced: the main thread, render thread, system compositor, audio stack, and network and storage subsystems. When you’re chasing a stutter that happens once every 30 seconds, or a battery drain that only appears on certain devices, those “below the framework” traces are often the only way to get a definitive answer.

You don’t need to memorize tools to benefit from them, but it helps to know what exists:

These tools are designed to answer concrete questions: “Which function is hot?”, “Which object is never released?”, “Which frame missed its deadline, and why?”

The toughest performance problems often hide in edge cases: a rare synchronization deadlock, a slow JSON parse on the main thread, a single view that triggers expensive layout, or a memory leak that only shows up after 20 minutes of use.

Native profiling lets you correlate symptoms (a freeze or jank) with causes (a specific call stack, allocation pattern, or GPU spike) instead of relying on trial-and-error changes.

Better visibility shortens time-to-fix because it turns debates into evidence. Teams can capture a trace, share it, and agree on the bottleneck quickly—often reducing days of “maybe it’s the network” speculation into a focused patch and a measurable before/after result.

Performance isn’t the only thing that breaks when you ship to millions of phones—consistency does. The same app can behave differently across OS versions, OEM customizations, and even vendor GPU drivers. Reliability at scale is the ability to keep your app predictable when the ecosystem isn’t.

On Android, OEM skins can tweak background limits, notifications, file pickers, and power management. Two devices on the “same” Android version may differ because vendors ship different system components and patches.

GPUs add another variable. Vendor drivers (Adreno, Mali, PowerVR) can diverge in shader precision, texture formats, and how aggressively they optimize. A rendering path that looks fine on one GPU can show flicker, banding, or rare crashes on another—especially around video, camera, and custom graphics.

iOS is tighter, but OS updates still shift behavior: permission flows, keyboard/autofill quirks, audio session rules, and background task policies can change subtly between minor versions.

Native platforms expose the “real” APIs first. When the OS changes, native SDKs and documentation usually reflect those changes immediately, and platform tooling (Xcode/Android Studio, system logs, crash symbols) aligns with what’s running on devices.

Cross-platform stacks add another translation layer: the framework, its rendering/runtime, and plugins. When an edge case appears, you’re debugging both your app and the bridge.

Framework upgrades can introduce runtime changes (threading, rendering, text input, gesture handling) that only fail on certain devices. Plugins can be worse: some are thin wrappers; others embed heavy native code with inconsistent maintenance.

At scale, reliability is rarely about one bug—it’s about reducing the number of layers where surprises can hide.

Some workloads punish even small amounts of overhead. If your app needs sustained high FPS, heavy GPU work, or tight control over decoding and buffers, native frameworks usually win because they can drive the platform’s fastest paths directly.

Native is a clear fit for 3D scenes, AR experiences, high-FPS games, video editing, and camera-first apps with real-time filters. These use cases aren’t just “compute heavy”—they’re pipeline heavy: you’re moving large textures and frames between CPU, GPU, camera, and encoders dozens of times per second.

Extra copies, late frames, or mismatched synchronization show up immediately as dropped frames, overheating, or laggy controls.

On iOS, native code can talk to Metal and the system media stack without intermediary layers. On Android, it can access Vulkan/OpenGL plus platform codecs and hardware acceleration through the NDK and media APIs.

That matters because GPU command submission, shader compilation, and texture management are sensitive to how the app schedules work.

A typical real-time pipeline is: capture or load frames → convert formats → upload textures → run GPU shaders → composite UI → present.

Native code can reduce overhead by keeping data in GPU-friendly formats longer, batching draw calls, and avoiding repeated texture uploads. Even one unnecessary conversion (say, RGBA ↔ YUV) per frame can add enough cost to break smooth playback.

On-device ML often depends on delegate/backends (Neural Engine, GPU, DSP/NPU). Native integration tends to expose these sooner and with more tuning options—important when you care about inference latency and battery.

You don’t always need a fully native app. Many teams keep a cross-platform UI for most screens, then add native modules for the hotspots: camera pipelines, custom renderers, audio engines, or ML inference.

This can deliver near-native performance where it counts, without rewriting everything else.

Picking a framework is less about ideology and more about matching user expectations to what the device must do. If your app feels instant, stays cool, and remains smooth under stress, users rarely ask what it’s built with.

Use these questions to narrow the choice quickly:

If you’re prototyping multiple directions, it can help to validate product flows quickly before you invest in deep native optimization. For example, teams sometimes use Koder.ai to spin up a working web app (React + Go + PostgreSQL) via chat, pressure-test the UX and data model, and then commit to a native or hybrid mobile build once the performance-critical screens are clearly defined.

Hybrid doesn’t have to mean “web inside an app.” For performance-critical products, hybrid usually means:

This approach limits risk: you can optimize the hottest paths without rewriting everything.

Before committing, build a small prototype of the hardest screen (e.g., live feed, editor timeline, map + overlays). Benchmark frame stability, input latency, memory, and battery over a 10–15 minute session. Use that data—not guesses—to choose.

If you do use an AI-assisted build tool like Koder.ai for early iterations, treat it as a speed multiplier for exploring architecture and UX—not a substitute for device-level profiling. Once you’re targeting a performance-critical experience, the same rule applies: measure on real devices, set performance budgets, and keep the critical paths (rendering, input, media) as close to native as your requirements demand.

Start by making the app correct and observable (basic profiling, logging, and performance budgets). Optimize only when you can point to a bottleneck that users will feel. This keeps teams from spending weeks shaving milliseconds off code that isn’t on the critical path.

It means the user experience breaks down when the app is even slightly slow or inconsistent. Small delays can cause missed moments (camera), wrong decisions (trading), or loss of trust (navigation), because performance is directly visible in the core interaction.

Because they talk to the platform’s APIs and rendering pipeline directly, with fewer translation layers. That usually means:

Common sources include:

Individually small costs can add up when they happen every frame or gesture.

Smoothness is about hitting the frame deadline consistently. At 60 Hz you have ~16.7 ms per frame; at 120 Hz ~8.3 ms. When you miss, users see stutter during scroll, animations, or gestures—often more noticeable than slightly slower overall load time.

The UI/main thread often coordinates input, layout, and drawing. Jank commonly happens when you do too much there, such as:

Keeping the main thread predictable is usually the biggest win for smoothness.

Latency is the felt gap between an action and response. Useful thresholds:

Performance-critical apps optimize the entire path from input → logic → render so responses are fast and consistent (low jitter).

Many hardware features are native-first and evolve quickly: advanced camera controls, AR, BLE background behavior, NFC, health APIs, and background execution policies. Cross-platform wrappers may cover basics, but advanced/edge behaviors often require direct native APIs to be reliable and up to date.

Because OS releases expose new APIs immediately in native SDKs, while cross-platform bindings/plugins may lag. That gap can cause:

Native reduces “waiting on the wrapper” risk for critical features.

Sustained performance is about efficiency over time:

Native APIs often let you schedule work more appropriately and use OS-accelerated media/graphics paths that waste less energy.

Yes. Many teams use a hybrid strategy:

This targets native effort where it matters most without rewriting everything.