Jul 09, 2025·8 min

Why PHP Still Powers the Web: Evolution, Strengths, Future

PHP keeps powering popular sites despite predictions of its end. Learn how it evolved, what it does well today, and when to choose it.

PHP keeps powering popular sites despite predictions of its end. Learn how it evolved, what it does well today, and when to choose it.

“PHP is dead” rarely means “nobody uses PHP.” Most of the time, it’s shorthand for “PHP isn’t the exciting new thing anymore,” or “I had a bad time with it once.” Those are very different claims.

When someone declares PHP dead, they’re usually reacting to a mix of perception and personal experience:

The web development world has a short attention span. Every few years, a new stack promises cleaner architecture, better performance, or a happier developer experience—so older mainstream tools become the punchline.

PHP also suffers from its own success: it was easy to start, so plenty of bad code was written early on. The worst examples became memes, and memes outlive context.

PHP doesn’t need constant excitement to stay relevant. It quietly runs an enormous amount of real traffic—especially through platforms like WordPress—and it remains a practical option on almost any web hosting.

This post isn’t about defending a favorite language. It’s about practical reality: where PHP is strong today, where it’s weak, and what that means if you’re building or maintaining software right now.

PHP started as a practical tool, not a grand platform. In the mid‑1990s it was essentially a set of simple scripts embedded in HTML—easy to drop into a page and immediately get dynamic output. That “just put it on the server” mindset became part of PHP’s DNA.

As the web grew, PHP 4 and especially PHP 5 rode a massive wave of inexpensive shared hosting. Providers could enable a PHP module once and suddenly thousands of small sites had access to server-side scripting without special setup.

This era also shaped the reputation PHP still carries: lots of copy‑pasted snippets, inconsistent coding styles, and applications that lived for years without major rewrites.

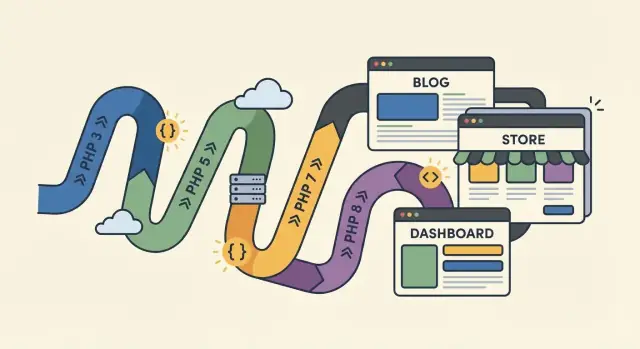

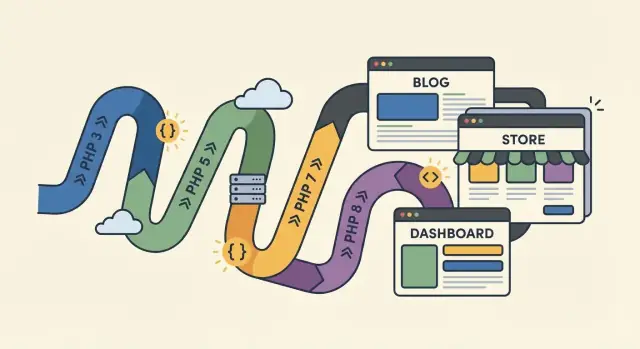

For a long time, PHP’s biggest strength was accessibility, not speed. PHP 7 changed that. The engine overhaul delivered major performance gains and reduced memory usage, which mattered to everyone from small blogs to high-traffic web apps. It also signaled that PHP wasn’t standing still—it was willing to modernize the core.

PHP 8 and later releases continued the shift toward “modern PHP”: better typing features, cleaner syntax, and more consistent behavior. These changes didn’t magically fix old code, but they made new codebases more predictable and easier to maintain.

PHP’s commitment to backward compatibility is a big reason adoption stayed high. You could upgrade hosting, update versions, and keep many older apps running. The tradeoff is that the internet accumulated a long tail of legacy code—still functioning, still deployed, and still influencing how people talk about PHP today.

PHP didn’t win early web development by being the most elegant language. It won by being the most reachable.

For a long time, the easiest way to put something dynamic online was simple: get cheap web hosting, upload a .php file, and it just ran. No special servers to configure, no complex deployment pipeline, and no extra runtime to install. That “drop in a file and refresh the browser” loop made PHP feel like an extension of HTML rather than a separate engineering discipline.

PHP fit the way the web worked: a browser requests a page, the server runs code, returns HTML, done. That model matched typical site needs—forms, sessions, logins, content pages—without forcing developers to think in long-running processes.

Even today, that design still maps cleanly to many products: marketing sites, content-driven applications, and CRUD-heavy dashboards.

Most early web apps were “read and write some data.” PHP made that approachable: connect to a database, run queries, render results. That ease helped countless small businesses ship features quickly—before “full-stack” was even a job title.

Once PHP was everywhere, it created its own gravity:

This history still matters. The web is built on continuity: maintaining, extending, and integrating what already exists. PHP’s reach—across shared hosting, CMS ecosystems, and frameworks like Laravel and Symfony—means choosing PHP isn’t just a language decision; it’s choosing a mature path through web development.

WordPress is the single biggest reason PHP never stopped being “useful.” When a huge portion of the web runs on one PHP-based platform, demand doesn’t just come from new builds—it comes from years (and sometimes decades) of ongoing updates, content changes, and extensions.

WordPress made publishing accessible, and it ran well on inexpensive shared hosting. That combination pushed hosting providers to optimize for PHP and made “PHP + MySQL” a default package almost anywhere you could buy hosting.

For businesses, the WordPress theme and plugin economy is the real engine. Instead of commissioning custom software, teams can often buy a plugin, add a theme, and get to market quickly. That keeps PHP relevant because most of that ecosystem is still written in PHP, maintained in PHP, and deployed to PHP-friendly hosting.

Many organizations continue running existing installs because:

In practice, that means a constant stream of maintenance work: security patches, plugin updates, performance tuning, and gradual modernization.

WordPress isn’t stuck in the past. Modern builds often use the REST API, the block editor (Gutenberg), and increasingly “headless” setups where WordPress manages content while a separate frontend consumes it. Even when the frontend shifts, PHP remains central on the backend—powering the admin, content model, permissions, and plugin hooks that businesses rely on.

“Modern PHP” usually doesn’t mean a single framework or a trendy rewrite. It means writing PHP the way the language has encouraged you to write it since PHP 7 and especially PHP 8+: clearer code, better tooling, and fewer surprises.

If your memory of PHP is loose arrays and mysterious warnings, PHP 8 will feel different.

Better typing is a big part of that shift. You can add type hints for function arguments and return values, use union types (like string|int), and rely on more consistent behavior from the engine. It doesn’t force you into strictness everywhere, but it makes “what is this value supposed to be?” much easier to answer.

PHP 8 also added features that reduce boilerplate and make intent clearer:

match expressions offer a cleaner, safer alternative to long switch blocks.Modern PHP is more opinionated about reporting problems early. Error messages have improved, many fatal mistakes are caught with clearer exceptions, and common development setups pair PHP with static analysis and formatting tools to surface issues before they reach production.

PHP itself has steadily improved its security posture through better defaults and sharper edges: stronger password APIs, better cryptography options, and more consistent handling of common failure cases. This doesn’t “secure your app” automatically—but it reduces the number of foot-guns available to you.

Modern PHP code tends to be organized into small, testable units, installed via Composer packages, and structured in a way that new teammates can understand quickly. That shift—more than any single feature—is why modern PHP feels like a different language than the one many people remember.

PHP’s performance story used to be defined by “interpretation.” Today it’s more accurate to think in terms of compilation, caching, and how well your app uses the database and memory.

OPcache stores precompiled script bytecode in memory, so PHP doesn’t need to parse and compile the same files on every request. That cuts CPU work dramatically, reduces request latency, and improves throughput—often without changing a line of application code.

For many sites, enabling and tuning OPcache is the single biggest “free” improvement: fewer CPU spikes, steadier response times, and better efficiency on shared hosting and containers alike.

PHP 8 introduced a JIT (Just-In-Time) compiler. It can speed up CPU-heavy workloads—think data processing, image manipulation, number crunching, or long-running workers.

But typical web requests are frequently bottlenecked elsewhere: database calls, network I/O, template rendering, and waiting on external APIs. In those cases, JIT usually doesn’t change your user-perceived speed much. It’s not useless—it’s just not a magic switch for most CRUD-style applications.

Performance depends on the whole stack:

Teams typically get the best results by profiling first, then applying targeted fixes: add caching where it’s safe, reduce expensive queries, and trim heavy dependencies (for example, overly complex WordPress plugins). This approach is less glamorous than chasing benchmarks—but it reliably moves real metrics like TTFB and p95 latency.

PHP didn’t stay relevant just because it was everywhere—it modernized because the ecosystem learned how to build and share code in a disciplined way. The biggest shift wasn’t a single feature in the language; it was the rise of shared tooling and conventions that made projects easier to maintain, upgrade, and collaborate on.

Composer turned PHP into a dependency-first ecosystem, similar to what developers expected in other communities. Instead of copying libraries into projects by hand, teams could declare dependencies, lock versions, and reproduce builds reliably.

That also encouraged better packaging: libraries became smaller, more focused, and easier to reuse across frameworks and custom applications.

The PHP-FIG’s PSR standards improved interoperability between tools and libraries. When common interfaces exist for things like autoloading (PSR-4), logging (PSR-3), HTTP messages (PSR-7), and containers (PSR-11), you can swap components without rewriting an entire app.

In practice, PSRs helped PHP projects feel less “framework-locked.” You can mix best-in-class packages while keeping your codebase consistent.

Symfony pushed professional engineering habits into mainstream PHP: reusable components, clear architecture patterns, and long-term support practices. Even developers who never used the full framework often rely on Symfony components under the hood.

Laravel made modern PHP feel approachable. It popularized conventions around routing, migrations, queues, and background jobs—plus a cohesive developer experience that nudged teams toward cleaner structure and more predictable projects.

Tooling matured alongside frameworks. PHPUnit became a default for unit and integration testing, making regression prevention part of normal workflows.

On the quality side, static analysis tools (high level: checking types, code paths, and potential bugs without running the code) helped teams refactor legacy code more safely and keep new code consistent—especially important when upgrading between PHP versions.

PHP’s biggest strength isn’t a single feature in PHP 8, or one famous framework. It’s the accumulated ecosystem: the libraries, integrations, conventions, and people who already know how to ship and maintain PHP applications. That maturity doesn’t trend on social media—but it quietly reduces risk.

When you build a real product, you spend less time writing “core” code and more time stitching together payments, email, logging, queues, storage, auth, and analytics. PHP’s ecosystem is unusually complete here.

Composer standardized dependency management years ago, which means common needs are solved in well-maintained packages instead of copy-pasted snippets. Laravel and Symfony ecosystems bring batteries-included components, while WordPress (for better and worse) provides endless integrations and plugins. The result: fewer reinventions, faster delivery, and clearer upgrade paths.

A language “survives” partly because teams can staff it. PHP is widely taught, widely used in web hosting, and familiar to many full-stack developers. Even if someone hasn’t used Laravel or Symfony, the learning curve to become productive is often shorter than in newer stacks—especially for server-side scripting and traditional web development.

That matters for small teams and agencies where turnover happens, deadlines are real, and the most expensive bug is the one nobody understands.

PHP’s documentation is a competitive advantage: it’s comprehensive, practical, and full of examples. Beyond the official docs, there’s a deep library of tutorials, books, courses, and community answers. Beginners can get started quickly, while experienced developers can dig into performance, testing, and architecture patterns without hitting dead ends.

Languages don’t die because they’re imperfect—they die when they’re too costly to maintain. PHP’s long history means:

That long-term maintenance story is unglamorous, but it’s why PHP remains a safe choice for systems meant to run for years, not weeks.

PHP’s reputation is often tied to “old-school” websites, but its day-to-day reality is modern: it runs in the same kinds of environments, talks to the same data stores, and supports the same API-first patterns as other backend languages.

PHP still shines on shared hosting—upload code, point a domain, and you’re live. That accessibility is a big reason it remains common for small businesses and content sites.

For teams that need more control, PHP works well on a VPS (single server you manage) or in containers (Docker + Kubernetes). Many production setups today run PHP-FPM behind Nginx, or use platform services that hide the infrastructure while keeping standard PHP workflows.

PHP is also appearing in serverless-style deployments. You may not always run “traditional” PHP request handling, but the idea is similar: short-lived processes that scale on demand, often packaged as containers.

Most PHP apps connect to MySQL/MariaDB—especially in WordPress-heavy environments—but PostgreSQL is equally common for new builds.

For speed, PHP teams often add Redis as a cache and sometimes as a queue backend. In practical terms, that means fewer database hits, faster page loads, and smoother traffic spikes—without changing the core product.

PHP isn’t limited to rendering HTML. It’s frequently used to build REST APIs that serve mobile apps, single-page web apps, or third-party integrations.

Authentication usually follows the same concepts you’ll see elsewhere: session + cookies for browser-based apps, and token-based auth for APIs (for example, bearer tokens or signed tokens). The details vary by framework and requirements, but the architectural patterns are mainstream.

Modern products often mix a PHP backend with a JavaScript frontend.

One approach is PHP serving the API while frameworks like React or Vue handle the interface. Another is a “hybrid” model where PHP renders core pages for speed and SEO, while JavaScript enhances specific parts of the UI. This lets teams choose what’s dynamic without forcing everything into a single style of application.

One reason “PHP is dead” rhetoric persists is that teams overestimate the cost of change. In practice, modern tooling can help you prototype or replace parts of a system without betting the business on a rewrite. For example, Koder.ai (a chat-driven vibe-coding platform) is useful when you want to spin up an admin dashboard, a small internal tool, or a React frontend that integrates with an existing PHP API—quickly, with a clear path to deployment and source code export.

PHP gets criticized a lot, and not all of it is just “old memes.” Some complaints are rooted in real history—especially if your only exposure is a decade-old codebase running on shared hosting. The key is separating the language from the way it was often used.

Fair point—especially if you judge PHP by its oldest standard library functions. Naming, parameter order, and return values weren’t always designed as a coherent system.

What’s changed: modern PHP development leans heavily on well-designed libraries and frameworks, with consistent interfaces. Day-to-day work is less about raw built-in functions and more about using Composer packages, typed code, and predictable APIs.

Also fair—because PHP was easy to deploy, it was easy to ship quick fixes, mix HTML with business logic, and skip tests. Many long-running apps carry that history.

But “legacy PHP” isn’t the same as “PHP.” A messy codebase can exist in any language; PHP just has a lot of old apps still generating revenue.

This one is often outdated. Plenty of slow sites are slow because of database queries, plugins, or inefficient application logic—not because of the runtime itself.

If you’re comparing modern PHP (with OPcache enabled) to early-2000s setups, you’re not comparing the same thing.

The practical fix is process, not heroics: adopt coding standards, require code review, add tests where the risk is highest, and modernize incrementally (upgrade PHP versions, introduce Composer, and refactor modules rather than rewriting everything at once).

PHP is a strong choice when you want to ship a reliable web product quickly, with predictable hosting and hiring options. It’s especially compelling when your project looks like “build pages, store data, manage users, integrate payments/CRM, and keep the admin experience simple.”

For many teams, PHP is at its best in:

If you need WordPress, PHP is the default: custom themes, plugins, and integrations are all part of the same ecosystem.

If you want a structured application without adopting WordPress, Laravel and Symfony offer mature conventions, dependency management via Composer, and strong communities—useful when you expect the codebase to grow over time.

PHP can be a weaker fit for:

Ask:

If most answers are “yes,” PHP is often the pragmatic pick.

PHP’s future is less about flashy reinvention and more about steady, useful progress: better performance defaults, clearer typing, stronger tooling, and continued support from major frameworks and hosts.

The biggest “future-proofing” move is simply keeping PHP and dependencies updated. Each major version cleans up older patterns and improves speed, but teams only benefit if they plan upgrades like a routine project, not an emergency.

A practical strategy is to upgrade in small steps (e.g., 7.4 → 8.0 → 8.1/8.2/8.3), using your CI pipeline to catch breaks early. Modern frameworks (Laravel, Symfony) and Composer make this manageable, but only if you keep them current too.

Keep an eye on:

Treat modernization as a series of small, reversible changes:

PHP endures because it’s widely deployable, well-supported, and still improving where it matters: real-world web delivery. Use it wisely by staying current, leaning on mature frameworks and tooling, and modernizing in measured steps that keep your business running.

No. The phrase usually means PHP isn’t the trendy choice, not that it’s unused. PHP still powers a large amount of production traffic—especially through WordPress—and remains widely supported by hosts and platforms.

Mostly history and perception:

“Modern PHP” typically means PHP 8+ plus current ecosystem practices:

Yes—many performance stereotypes are outdated. Real speed comes from the whole stack, but PHP can be very fast when you:

OPcache caches precompiled PHP bytecode in memory so PHP doesn’t re-parse and re-compile files on every request. In many apps it’s the biggest “free” win:

Sometimes, but not usually for typical web pages. PHP 8’s JIT helps most in CPU-heavy workloads (e.g., image processing, numeric computation, long-running workers). Many web requests are dominated by database and network I/O, so JIT often has minimal user-visible impact.

Composer is PHP’s dependency manager. It lets you declare packages, lock versions, and reproduce builds reliably—replacing the old “copy library files into the project” approach. In practice, it enables modern workflows: autoloading, smaller reusable libraries, and safer upgrades.

They matter because they standardize interfaces across the ecosystem (autoloading, logging, HTTP messages, containers, etc.). That makes libraries interoperable and reduces lock-in:

PHP is a strong fit when you need to ship and maintain a web product with predictable hosting and hiring:

Frameworks like Laravel/Symfony are good when you want structure without adopting a CMS.

Plan incremental modernization instead of rewrites:

This reduces risk while steadily improving maintainability and security.