Nov 14, 2025·8 min

Why Read Replicas Exist and When They Actually Help

Learn why read replicas exist, what problems they solve, and when they help (or hurt). Includes common use cases, limits, and practical decision tips.

What a Read Replica Is (and Isn’t)

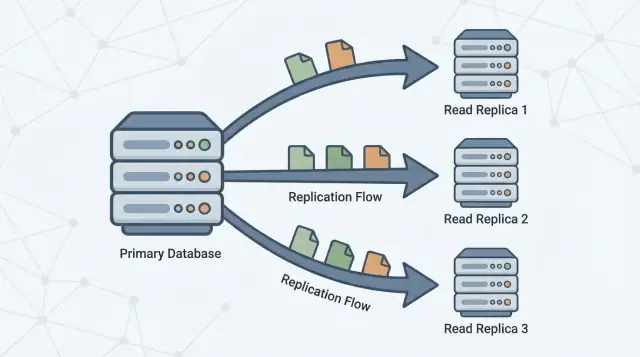

A read replica is a copy of your main database (often called the primary) that stays up to date by continuously receiving changes from it. Your application can send read-only queries (like SELECT) to the replica, while the primary continues to handle all writes (like INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE).

The basic promise

The promise is simple: more read capacity without putting more pressure on the primary.

If your app has lots of “fetch” traffic—homepages, product pages, user profiles, dashboards—moving some of those reads to one or more replicas can free the primary to focus on write work and critical reads. In many setups, this can be done with minimal application change: you keep one database as the source of truth and add replicas as additional places to query.

What a read replica is not

Read replicas are useful, but they’re not a magic performance button. They do not:

- Increase write capacity. All writes still land on the primary.

- Fix slow queries. If a query is inefficient (missing indexes, scanning huge tables, bad join patterns), it will likely be slow on replicas too—just slower somewhere else.

- Replace good schema and data design. Replicas don’t solve hot spots, oversized rows, or an overgrown “everything table.”

- Eliminate the need to monitor. Replicas add moving parts: lag, connection limits, and failover behavior.

Setting expectations for the rest of the guide

Think of replicas as a read-scaling tool with trade-offs. The rest of this article explains when they actually help, the common ways they backfire, and how concepts like replication lag and eventual consistency affect what users see when you start reading from a copy instead of the primary.

Why Read Replicas Exist

A single primary database server often starts out feeling “big enough.” It handles writes (inserts, updates, deletes) and it also answers every read request (SELECT queries) from your app, dashboards, and internal tools.

As usage grows, reads usually multiply faster than writes: every page view might trigger several queries, search screens can fan out into many lookups, and analytics-style queries can scan lots of rows. Even if your write volume is moderate, the primary can still become a bottleneck because it has to do two jobs at once: accept changes safely and quickly, and serve a growing pile of read traffic with low latency.

Separating reads from writes

Read replicas exist to split that workload. The primary stays focused on processing writes and maintaining the “source of truth,” while one or more replicas handle read-only queries. When your application can route some queries to replicas, you reduce CPU, memory, and I/O pressure on the primary. That typically improves overall responsiveness and leaves more headroom for write bursts.

Replication in one sentence

Replication is the mechanism that keeps replicas up to date by copying changes from the primary to other servers. The primary records changes, and replicas apply those changes so they can answer queries using nearly the same data.

This pattern is common across many database systems and managed services (for example PostgreSQL, MySQL, and cloud-hosted variants). The exact implementation differs, but the goal is the same: increase read capacity without forcing your primary to scale vertically forever.

How Replication Works (Simple Mental Model)

Think of a primary database as the “source of truth.” It accepts every write—creating orders, updating profiles, recording payments—and assigns those changes a definite order.

One or more read replicas then follow the primary, copying those changes so they can answer read queries (like “show my order history”) without putting more load on the primary.

The basic flow

- Primary accepts writes and records them in a durable log (the exact name varies by database).

- Replicas stream or fetch those log entries from the primary.

- Replicas replay the same changes in the same order, gradually catching up.

Reads can be served from replicas, but writes still go to the primary.

Synchronous vs. asynchronous replication (high level)

Replication can happen in two broad modes:

- Synchronous: the primary waits for a replica (or a quorum) to confirm it received the change before the write is considered “committed.” This reduces stale reads, but it can increase write latency and make writes more sensitive to replica/network issues.

- Asynchronous: the primary commits the write immediately, and replicas catch up afterward. This keeps writes fast and resilient, but replicas can temporarily be behind.

Replication lag and “eventual consistency”

That delay—replicas being behind the primary—is called replication lag. It’s not automatically a failure; it’s often the normal trade-off you accept to scale reads.

For end users, lag shows up as eventual consistency: after you change something, the system will become consistent everywhere, but not necessarily instantly.

Example: you update your email address and refresh your profile page. If the page is served from a replica that’s a few seconds behind, you might briefly see the old email—until the replica applies the update and “catches up.”

When Read Replicas Actually Help

Read replicas help when your primary database is healthy for writes but gets overwhelmed serving read traffic. They’re most effective when you can offload a meaningful chunk of SELECT load without changing how you write data.

Signs you’re read-bound (not write-bound)

Look for patterns like:

- High CPU on the primary during traffic peaks, while write throughput isn’t unusually high

- A very high ratio of

SELECTqueries compared toINSERT/UPDATE/DELETE - Read queries getting slower during peaks even though writes remain stable

- Connection pool saturation driven by read-heavy endpoints (product pages, feeds, search results)

How to confirm reads are the problem (metrics to check)

Before adding replicas, validate with a few concrete signals:

- CPU vs I/O: Is the primary CPU pegged when read latency spikes? Or is disk read I/O the bottleneck?

- Query mix: Percentage of time spent in

SELECTstatements (from your slow query log/APM). - p95/p99 read latency: Track read endpoints and database query latency separately.

- Buffer/cache hit rate: A low hit rate can mean reads are forcing disk access.

- Top queries by total time: One expensive query can dominate “read load.”

Don’t skip cheaper fixes

Often, the best first move is tuning: add the right index, rewrite one query, reduce N+1 calls, or cache hot reads. These changes can be faster and cheaper than operating replicas.

Quick checklist: replicas vs tuning

Choose replicas if:

- Most load is read traffic, and reads are already reasonably optimized

- You can tolerate occasional stale reads for the offloaded queries

- You need additional capacity quickly without risky schema/query changes

Choose tuning first if:

- A few queries dominate total read time

- Missing indexes or inefficient joins are obvious

- Reads are slow even at low traffic (a sign of query design issues)

Best-Fit Use Cases

Read replicas are most valuable when your primary database is busy handling writes (checkouts, sign-ups, updates), but a big share of traffic is read-heavy. In a primary–replica architecture, pushing the right queries to replicas improves database performance without changing application features.

1) Dashboards and analytics that shouldn’t slow transactions

Dashboards often run long queries: grouping, filtering across large date ranges, or joining multiple tables. Those queries can compete with transactional work for CPU, memory, and cache.

A read replica is a good place for:

- Internal reporting workloads

- Admin dashboards

- “Daily/weekly metrics” views

You keep the primary focused on fast, predictable transactions while analytics reads scale independently.

2) Search and browse pages with heavy read volume

Catalog browsing, user profiles, and content feeds can produce a high volume of similar read queries. When that read scaling pressure is the bottleneck, replicas can absorb traffic and reduce latency spikes.

This is especially effective when reads are cache-miss heavy (many unique queries) or when you can’t rely solely on an application cache.

3) Background jobs that scan lots of data

Exports, backfills, recomputing summaries, and “find every record that matches X” jobs can thrash the primary. Running these scans against a replica is often safer.

Just make sure the job tolerates eventual consistency: with replication lag, it may not see the newest updates.

4) Multi-region reads for lower latency (with staleness caveats)

If you serve users globally, placing read replicas closer to them can reduce round-trip time. The trade-off is stronger exposure to stale reads during lag or network issues, so it’s best for pages where “nearly up to date” is acceptable (browse, recommendations, public content).

Where Replicas Can Backfire

Get Credits for Shipping

Share what you build with Koder.ai and earn credits through the content program.

Read replicas are great when “close enough” is good enough. They backfire when your product quietly assumes every read reflects the latest write.

The classic symptom: “I just updated it, why didn’t it change?”

A user edits their profile, submits a form, or changes account settings—and the next page load pulls from a replica that’s a few seconds behind. The update succeeded, but the user sees old data and retries, double-submits, or loses trust.

This is especially painful in flows where the user expects immediate confirmation: changing an email address, toggling preferences, uploading a document, or posting a comment and then being redirected back.

“Must be current” screens (don’t gamble here)

Some reads can’t tolerate being stale, even briefly:

- Shopping carts and checkout totals

- Wallet balances, loyalty points, inventory counts

- “Did my payment go through?” status screens

If a replica is behind, you can show the wrong cart total, oversell stock, or display an outdated balance. Even if the system later corrects itself, the user experience (and support volume) takes the hit.

Admin and operations tools need the freshest truth

Internal dashboards often drive real decisions: fraud review, customer support, order fulfillment, moderation, and incident response. If an admin tool reads from replicas, you risk acting on incomplete data—e.g., refunding an order that was already refunded, or missing the latest status change.

Practical fix: route “read-your-writes” to primary

A common pattern is conditional routing:

- After a user writes, send their subsequent “confirmation” reads to the primary for a short window (seconds to minutes).

- Keep background, anonymous, or non-critical reads on replicas.

This preserves the benefits of replicas without turning consistency into a guessing game.

Understanding Replication Lag and Stale Reads

Replication lag is the delay between when a write is committed on the primary database and when that same change becomes visible on a read replica. If your app reads from a replica during that delay, it can return “stale” results—data that was true a moment ago, but not anymore.

Why lag happens

Lag is normal, and it usually grows under stress. Common causes include:

- Load spikes on the primary: lots of writes means more changes to ship and apply.

- Replica underpowered or busy: the replica can’t apply changes as fast as they arrive (CPU, disk I/O).

- Network latency or jitter: delays in moving the replication stream.

- Large transactions / bulk updates: a single big change can take time to serialize, transfer, and replay.

How stale reads show up in product behavior

Lag doesn’t just affect “freshness”—it affects correctness from a user’s perspective:

- A user updates their profile, then refreshes and sees the old value.

- “Unread messages” or notification badges drift because counts are computed from slightly old rows.

- Admin/reporting screens miss the latest orders, refunds, or status changes.

Practical ways to handle it

Start by deciding what your feature can tolerate:

- Add a tolerance window: “Data may be up to 30 seconds old” is acceptable for many dashboards.

- Route read-after-write to primary: after a user changes something, read that entity from the primary for a short period.

- UI messaging: set expectations (“Updating…”, “May take a few seconds to appear”).

- Retry logic: if a critical read is missing a just-written record, retry against the primary or retry after a short delay.

What to monitor and alert on

Track replica lag (time/bytes behind), replica apply rate, replication errors, and replica CPU/disk I/O. Alert when lag exceeds your agreed tolerance (e.g., 5s, 30s, 2m) and when lag keeps increasing over time (a sign the replica will never catch up without intervention).

Read Scaling vs Write Scaling (Key Trade-Offs)

Make Changes with Confidence

Test migrations and rollbacks safely while you work through replication trade-offs.

Read replicas are a tool for read scaling: adding more places to serve SELECT queries. They are not a tool for write scaling: increasing how many INSERT/UPDATE/DELETE operations your system can accept.

Scaling reads: what replicas are good at

When you add replicas, you add read capacity. If your application is bottlenecked on read-heavy endpoints (product pages, feeds, lookups), you can spread those queries across multiple machines.

This often improves:

- Query latency under load (less contention on the primary)

- Throughput for reads (more CPU/memory/I/O available for

SELECTs) - Isolation for heavy reads, like reporting workloads, so they don’t interfere with transactional traffic

Scaling writes: what replicas don’t do

A common misconception is that “more replicas = more write throughput.” In a typical primary-replica setup, all writes still go to the primary. In fact, more replicas can slightly increase work for the primary, because it must generate and ship replication data to every replica.

If your pain is write throughput, replicas won’t fix it. You’re usually looking at different approaches (query/index tuning, batching, partitioning/sharding, or changing the data model).

Connection limits and pooling: the hidden bottleneck

Even if replicas give you more read CPU, you can still hit connection limits first. Each database node has a maximum number of concurrent connections, and adding replicas can multiply the number of places your app could connect—without reducing the total demand.

Practical rule: use connection pooling (or a pooler) and keep your per-service connection counts intentional. Otherwise, replicas can simply become “more databases to overload.”

Cost trade-offs: capacity isn’t free

Replicas add real costs:

- More nodes (compute spend)

- More storage (each replica typically stores a full copy)

- More operations effort (monitoring lag, backups/restore strategy, schema changes, incident response)

The trade-off is simple: replicas can buy you read headroom and isolation, but they add complexity and don’t move the write ceiling.

High Availability and Failover: What Replicas Can Do

Read replicas can improve read availability: if your primary is overloaded or briefly unavailable, you may still be able to serve some read-only traffic from replicas. That can keep customer-facing pages responsive (for content that tolerates slightly stale data) and reduce the blast radius of a primary incident.

What replicas don’t provide is a complete high-availability plan by themselves. A replica is usually not ready to take writes automatically, and a “readable copy exists” is different from “the system can safely and quickly accept writes again.”

Promotion and failover (conceptually)

Failover typically means: detect primary failure → pick a replica → promote it to become the new primary → redirect writes (and usually reads) to the promoted node.

Some managed databases automate most of this, but the core idea stays the same: you’re changing who is allowed to accept writes.

Key risks to plan around

- Stale replica data: the replica may be behind. If you promote it, you might lose the most recent writes that never replicated.

- Split-brain avoidance: you must prevent two nodes from accepting writes at the same time. This is why promotions are usually gated by a single authority (a managed control plane, a quorum system, or strict operational procedures).

- Routing and caches: your app needs a reliable way to switch targets—connection strings, DNS, proxies, or a database router. Make sure write traffic can’t “accidentally” keep going to the old primary.

Test it like a feature

Treat failover as something you practice. Run game-day tests in staging (and carefully in production during low-risk windows): simulate primary loss, measure time-to-recover, verify routing, and confirm your app handles read-only periods and reconnections cleanly.

Practical Routing Patterns (Read/Write Splitting)

Read replicas only help if your traffic actually reaches them. “Read/write splitting” is the set of rules that sends writes to the primary and eligible reads to replicas—without breaking correctness.

Pattern 1: Split in the application

The simplest approach is explicit routing in your data access layer:

- All writes (

INSERT/UPDATE/DELETE, schema changes) go to the primary. - Only selected reads are allowed to use a replica.

This is easy to reason about and easy to roll back. It’s also where you can encode business rules like “after checkout, always read order status from primary for a while.”

Pattern 2: Split via a proxy or driver

Some teams prefer a database proxy or smart driver that understands “primary vs replica” endpoints and routes based on query type or connection settings. This reduces application code changes, but be careful: proxies can’t reliably know which reads are “safe” from a product perspective.

Choosing which queries can safely go to replicas

Good candidates:

- Analytics, reporting workloads, dashboards

- Search/browse pages where slightly stale data is acceptable

- Background jobs that retry and don’t need the latest value

Avoid routing reads that immediately follow a user write (e.g., “update profile → reload profile”) unless you have a consistency strategy.

Transactions and session consistency

Within a transaction, keep all reads on the primary.

Outside transactions, consider “read-your-writes” sessions: after a write, pin that user/session to the primary for a short TTL, or route specific follow-up queries to the primary.

Start small and measure

Add one replica, route a limited set of endpoints/queries, and compare before/after:

- Primary CPU and read IOPS

- Replica utilization

- Error rate and latency percentiles

- Incidents tied to stale reads

Expand routing only when the impact is clear and safe.

Monitoring and Operations Basics

Scaffold a Safe Data Layer

Create a clean data access layer you can extend for read write splitting later.

Read replicas aren’t “set and forget.” They’re extra database servers with their own performance limits, failure modes, and operational chores. A little monitoring discipline is usually the difference between “replicas helped” and “replicas added confusion.”

What to watch (the few metrics that matter)

Focus on indicators that explain user-facing symptoms:

- Replica lag: how far behind the primary a replica is (seconds, bytes, or WAL/LSN position depending on the database). This is your early warning for stale reads.

- Replication errors: broken connections, auth failures, disk-full, or replication slot issues. Treat these as incidents, not “noise.”

- Query latency (p50/p95) on replicas vs primary: replicas can be slow even when the primary is fine (different cache state, different hardware, long reports).

- Cache hit rate: a replica that’s constantly missing cache may show higher latency after restarts or traffic shifts.

Capacity planning: how many replicas do you need?

Start with one replica if your goal is offloading reads. Add more when you have a clear constraint:

- Read throughput: one replica can’t keep up with peak QPS or heavy analytical queries.

- Isolation: dedicate a replica to reporting workloads so dashboards don’t steal resources from user traffic.

- Geography: a replica per region can cut read latency, but increases operational overhead.

A practical rule: scale replicas only after you’ve confirmed reads are the bottleneck (not indexes, slow queries, or app caching).

Common operational tasks

- Backups: decide where backups run. Taking backups from a replica can reduce load on the primary, but verify consistency requirements and that the replica is healthy.

- Schema changes: test migrations with replication in mind (long-running DDL can increase lag). Coordinate rollouts so app and schema changes remain compatible during propagation.

- Maintenance windows: patching or restarting replicas temporarily reduces read capacity. Plan rotation so you don’t drop below your required read headroom.

Troubleshooting checklist: “replicas are slow”

- Check replica lag: if it’s high, users may be retrying or seeing stale data.

- Compare slow query logs on replica vs primary: reporting queries often surface here.

- Verify CPU, memory, disk I/O, and network on the replica host.

- Look for lock contention or long-running transactions on the primary that delay replication.

- Confirm your read routing isn’t overloading a single replica (uneven load balancing).

- Validate indexes exist on replicas (they should mirror the primary) and statistics are up to date.

Alternatives and a Simple Decision Framework

Read replicas are one tool for read scaling, but they’re rarely the first lever to pull. Before adding operational complexity, check whether a simpler fix gets you the same outcome.

Alternatives to try first

Caching can remove entire classes of reads from your database. For “read-mostly” pages (product details, public profiles, configuration), an application cache or CDN can cut load dramatically—without introducing replication lag.

Indexes and query optimization often outperform replicas for the common case: a few expensive queries burning CPU. Adding the right index, reducing SELECT columns, avoiding N+1 queries, and fixing bad joins can turn “we need replicas” into “we just needed a better plan.”

Materialized views / pre-aggregation help when the workload is inherently heavy (analytics, dashboards). Instead of re-running complex queries, you store computed results and refresh on a schedule.

When to consider sharding/partitioning instead

If your writes are the bottleneck (hot rows, lock contention, write IOPS limits), replicas won’t help much. That’s when partitioning tables by time/tenant, or sharding by customer ID, can spread write load and reduce contention. It’s a bigger architectural step, but it addresses the real constraint.

A simple decision framework

Ask four questions:

- What’s the goal? Reduce read latency, offload reporting workloads, or improve high availability?

- How fresh must reads be? If you can’t tolerate stale reads, replicas may cause user-visible issues.

- What’s your budget? Replicas add infrastructure cost and ongoing monitoring/operations.

- How much complexity can you absorb? Read/write splitting, handling eventual consistency, and failover testing are non-trivial.

If you’re prototyping a new product or spinning up a service quickly, it helps to bake these constraints into the architecture early. For example, teams building on Koder.ai (a vibe-coding platform that generates React apps with Go + PostgreSQL backends from a chat interface) often start with a single primary for simplicity, then graduate to replicas as soon as dashboards, feeds, or internal reporting begin competing with transactional traffic. Using a planning-first workflow makes it easier to decide upfront which endpoints can tolerate eventual consistency and which must be “read-your-writes” from the primary.

If you want help choosing a path, see /pricing for options, or browse related guides in /blog.

FAQ

What is a read replica in plain terms?

A read replica is a copy of your primary database that continuously receives changes and can answer read-only queries (for example, SELECT). It helps you add read capacity without increasing load on the primary for those reads.

Do read replicas increase write throughput?

No. In a typical primary–replica setup, all writes still go to the primary. Replicas can even add a bit of overhead because the primary must ship changes to each replica.

When do read replicas actually help performance?

Mostly when you’re read-bound: lots of SELECT traffic is driving CPU/I/O or connection pressure on the primary, while write volume is relatively stable. They’re also useful to isolate heavy reads (reporting, exports) from transactional workloads.

Will adding replicas fix slow queries?

Not necessarily. If a query is slow due to missing indexes, poor joins, or scanning too much data, it will often be slow on a replica too—just slow somewhere else. Tune queries and indexes first when a few queries dominate total time.

What is replication lag, and why does it matter?

Replication lag is the delay between a write being committed on the primary and that change becoming visible on a replica. During lag, replica reads can be stale, which is why systems using replicas often behave with eventual consistency for some reads.

What causes replication lag to get worse?

Common causes include:

- Write spikes (more changes to ship)

- Underpowered/busy replica (can’t apply changes fast enough)

- Network latency/jitter

- Large transactions or bulk updates that take time to replay

Which parts of an app should NOT read from replicas?

Avoid replicas for reads that must reflect the latest write, such as:

- Checkout totals, carts, inventory

- Wallet/balance and payment status

- Admin/ops actions that require the freshest truth

For these, prefer reading from the primary, at least in critical paths.

How do you prevent “I just updated it, why didn’t it change?” issues?

Use a read-your-writes strategy:

- After a user performs a write, route their follow-up confirmation reads to the primary for a short TTL (seconds to minutes).

- Keep non-critical/anonymous/background reads on replicas.

- Optionally retry against primary if a just-written record is missing.

What should you monitor for read replicas?

Track a small set of signals:

- Replica lag (time/bytes/LSN behind)

- Replication errors (disconnects, auth, disk full)

- Query latency (p50/p95) on replica vs primary

- Replica CPU/disk I/O utilization

Alert when lag exceeds your product’s tolerance (for example, 5s/30s/2m).

What are good alternatives to adding read replicas?

Common alternatives include:

- Caching (app cache/CDN) to remove reads entirely

- Indexing and query optimization (often the biggest win)

- Materialized views / pre-aggregation for dashboards

- Partitioning/sharding if writes or contention are the real bottleneck

Replicas are best when reads are already reasonably optimized and you can tolerate some staleness.