Jun 25, 2025·8 min

Why State Management Is One of the Hardest Frontend Problems

State management is hard because apps juggle many sources of truth, async data, UI interactions, and performance tradeoffs. Learn patterns to cut bugs.

What “State” Really Means in a Frontend App

A plain-language definition

In a frontend app, state is simply the data your UI depends on that can change over time.

When state changes, the screen should update to match. If the screen doesn’t update, updates inconsistently, or shows a mix of old and new values, you feel “state problems” immediately—buttons that stay disabled, totals that don’t match, or a view that doesn’t reflect what the user just did.

Common examples you see every day

State shows up in both small and big interactions, such as:

- Form inputs: what the user typed, whether a checkbox is checked, which errors to show

- Navigation choices: selected tab, current step in a wizard, expanded/collapsed sections

- Shopping/cart data: items, quantities, applied coupons, calculated totals

- User session: logged-in user info, permissions, feature flags, “remember me” preferences

Some of these are “temporary” (like a selected tab), while others feel “important” (like a cart). They’re all state because they influence what the UI renders right now.

Why state is more than “variables in a component”

A plain variable only matters where it lives. State is different because it has rules:

- Ownership: which part of the app is allowed to change it

- Update flow: when and how changes trigger re-renders

- Consistency: ensuring multiple UI pieces don’t drift out of sync

The real goal of state management isn’t storing data—it’s making updates predictable so the UI stays consistent. When you can answer “what changed, when, and why,” state becomes manageable. When you can’t, even simple features turn into surprises.

Why State Feels Easy at First (Then Suddenly Isn’t)

At the start of a frontend project, state feels almost boring—in a good way. You have one component, one input, and one obvious update. A user types into a field, you save that value, and the UI re-renders. Everything is visible, immediate, and contained.

The simple case: one component, one update

Imagine a single text input that previews what you typed:

- The state lives in the same component that renders the input.

- The update happens in direct response to a user action.

- There’s no debate about “who owns” the data.

In that setup, state is basically: a variable that changes over time. You can point to where it’s stored and where it’s updated, and you’re done.

Why local component state feels straightforward

Local state works because the mental model matches the code structure:

- Scope is small (one component, maybe a couple of children).

- Updates are synchronous from the user’s point of view.

- Data flow is obvious: input → update → render.

Even if you use a framework like React, you don’t need to think deeply about architecture. The defaults are enough.

What changes as the app grows

As soon as the app stops being “a page with a widget” and becomes “a product,” state stops living in one place.

Now the same piece of data might be needed across:

- multiple screens (navigation)

- distant components (shared UI)

- reloads and restarts (persistence)

- multiple users/devices (server synchronization)

A profile name might be shown in a header, edited in a settings page, cached for faster loading, and also used to personalize a welcome message. Suddenly, the question isn’t “how do I store this value?” but “where should this value live so it stays correct everywhere?”

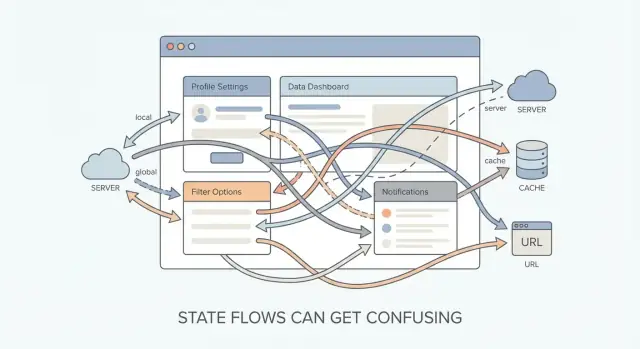

Complexity rises non-linearly

State complexity doesn’t grow gradually with features—it jumps.

Adding a second place that reads the same data isn’t “twice as hard.” It introduces coordination problems: keeping views consistent, preventing stale values, deciding what updates what, and handling timing. Once you have a few shared pieces of state plus async work, you can end up with behavior that’s difficult to reason about—even though each individual feature still looks simple on its own.

Too Many Sources of Truth

State gets painful when the same “fact” is stored in more than one place. Each copy can drift, and now your UI is arguing with itself.

The usual suspects

Most apps end up with several places that can hold “truth”:

- Server data (your API/database): the canonical record

- Client cache (e.g., data fetching library cache): a local mirror meant to be refreshed

- Local UI state (component state): what the user is doing right now

- URL (path, query params, hash): state you can bookmark, share, and restore

All of these are valid owners for some state. The trouble starts when they all try to own the same state.

How duplication happens

A common pattern: fetch server data, then copy it into local state “so we can edit it.” For example, you load a user profile and set formState = userFromApi. Later, the server refetches (or another tab updates the record), and now you have two versions: the cache says one thing, your form says another.

Duplication also sneaks in through “helpful” transformations: storing both items and itemsCount, or storing selectedId and selectedItem.

Symptoms you’ll recognize

When there are multiple sources of truth, bugs tend to sound like:

- “It works on this screen only.”

- The UI is inconsistent after navigation or refresh.

- Data looks correct in one component but stale in another.

- Saving succeeds, but the list view doesn’t update (or updates twice).

Rule of thumb

For each piece of state, pick one owner—the place where updates are made—and treat everything else as a projection (read-only, derived, or synced in a single direction). If you can’t point to the owner, you’re probably storing the same truth twice.

Async Work and Side Effects Make State Tricky

A lot of frontend state feels simple because it’s synchronous: a user clicks, you set a value, the UI updates. Side effects break that neat, step-by-step story.

What counts as a side effect?

Side effects are any actions that reach outside your component’s pure “render based on data” model:

- Network calls (fetching, saving, retrying)

- Timers and debouncing (setTimeout, intervals)

- Subscriptions (web sockets, event listeners)

- Browser storage (localStorage/sessionStorage)

Each one can fire later, fail unexpectedly, or run more than once.

Why async state is harder than sync state

Async updates introduce time as a variable. You no longer reason about “what happened,” but “what might still be happening.” Two requests can overlap. A slow response can arrive after a newer one. A component can unmount while an async callback still tries to update state.

That’s why bugs often look like:

- Loading flags stuck forever (error path didn’t clear them, or request was cancelled)

- UI flashing old data (stale cached value shown as “final”)

- Outdated responses overwriting new ones (request A finishes after request B)

A simple strategy: model the request explicitly

Instead of sprinkling booleans like isLoading across the UI, treat async work as a small state machine:

- idle (nothing started)

- loading (in progress)

- success (data available)

- error (failure captured)

Track the data and the status together, and keep an identifier (like a request id or query key) so you can ignore late responses. This makes “what should the UI show right now?” a straightforward decision, not a guess.

UI State vs Server State (They Look Similar, But Aren’t)

A lot of state headaches start with a simple mix-up: treating “what the user is doing right now” the same as “what the backend says is true.” They can both change over time, but they follow different rules.

UI state: what the interface is doing

UI state is temporary and interaction-driven. It exists to render the screen the way the user expects in this moment.

Examples include modals being open/closed, active filters, a search input draft, hover/focus, which tab is selected, and pagination UI (current page, page size, scroll position).

This state is usually local to a page or component tree. It’s fine if it resets when you navigate away.

Server state: what you fetched (and what might change elsewhere)

Server state is data from an API: user profiles, product lists, permissions, notifications, saved settings. It’s “remote truth” that can change without your UI doing anything (someone else edits it, the server recalculates it, a background job updates it).

Because it’s remote, it also needs metadata: loading/error states, cache timestamps, retries, and invalidation.

Why mixing them causes confusion

If you store UI drafts inside server data, a refetch can wipe local edits. If you store server responses inside UI state without caching rules, you’ll fight stale data, duplicate fetches, and inconsistent screens.

A common failure mode: the user edits a form while a background refetch finishes, and the incoming response overwrites the draft.

A practical guideline

Manage server state with caching patterns (fetch, cache, invalidate, refetch on focus) and treat it as shared and asynchronous.

Manage UI state with UI tools (local component state, context for truly shared UI concerns), and keep drafts separate until you intentionally “save” them back to the server.

Derived State and the “Don’t Store What You Can Compute” Rule

Get Rewarded for Learning

Earn credits by creating content about what you build and how you designed state.

Derived state is any value you can compute from other state: a cart total from line items, a filtered list from the original list + a search query, or a “canSubmit” flag from field values and validation rules.

It’s tempting to store these values because it feels convenient (“I’ll just keep total in state too”). But as soon as the inputs change in more than one place, you risk drift: the stored total no longer matches the items, the filtered list doesn’t reflect the current query, or the submit button stays disabled after fixing an error. These bugs are annoying because nothing looks “wrong” in isolation—each state variable is valid on its own, just inconsistent with the rest.

Prefer selectors / computed values

A safer pattern is: store the minimal source of truth, and compute everything else at read time. In React this can be a simple function, or a memoized calculation.

const items = useCartItems();

const total = items.reduce((sum, item) => sum + item.price * item.qty, 0);

const filtered = products.filter(p => p.name.includes(query));

In larger apps, “selectors” (or computed getters) formalize this idea: one place defines how to derive total, filteredProducts, visibleTodos, and every component uses the same logic.

When caching derived values is OK

Computing on every render is usually fine. Cache when you’ve measured a real cost: expensive transformations, huge lists, or derived values shared across many components. Use memoization (useMemo, selector memoization) so the cache keys are the true inputs—otherwise you’re back to drift, just wearing a performance hat.

Global vs Local: Choosing the Right Owner

State gets painful when it’s unclear who owns it.

What “ownership” means

The owner of a piece of state is the place in your app that has the right to update it. Other parts of the UI may read it (via props, context, selectors, etc.), but they shouldn’t be able to change it directly.

Clear ownership answers two questions:

- Who can update this value? (the owner)

- Who can read this value? (any consumers)

When those boundaries blur, you get conflicting updates, “why did this change?” moments, and components that are difficult to reuse.

Global state: convenient, but coupling sneaks in

Putting state in a global store (or top-level context) can feel clean: anything can access it, and you avoid prop drilling. The tradeoff is unintended coupling—suddenly unrelated screens depend on the same values, and small changes ripple across the app.

Global state is a good fit for things that are truly cross-cutting, like the current user session, app-wide feature flags, or a shared notification queue.

Lift state up—only as far as needed

A common pattern is to start local and “lift” state to the nearest common parent only when two sibling parts need to coordinate.

If only one component needs the state, keep it there. If multiple components need it, lift it to the smallest shared owner. If many distant areas need it, then consider global.

A simple heuristic

Keep state close to where it’s used unless sharing is required.

This keeps components easier to understand, reduces accidental dependencies, and makes future refactors less scary because fewer parts of the app are allowed to mutate the same data.

Concurrency, Races, and Out-of-Order Updates

Practice Async Patterns

Create a small app to practice request IDs, cancellations, and optimistic updates.

Frontend apps feel “single-threaded,” but user input, timers, animations, and network requests all run independently. That means multiple updates can be in flight at once—and they don’t necessarily finish in the order you started them.

When updates collide

A common collision: two parts of the UI update the same state.

- A search box updates

queryon every keystroke. - A filter dropdown updates

query(or the same results list) when changed.

Individually, each update is correct. Together, they can overwrite each other depending on timing. Even worse, you can end up showing results for a previous query while the UI displays the new filters.

Race conditions: fast users, slow networks

Race conditions show up when you fire request A, then quickly fire request B—but request A returns last.

Example: the user types “c”, “ca”, “cat”. If the “c” request is slow and the “cat” request is fast, the UI might briefly show “cat” results and then get overwritten by stale “c” results when that older response finally arrives.

The bug is subtle because everything “worked”—just in the wrong order.

Techniques that reduce out-of-order bugs

You generally want one of these strategies:

- Cancel the previous request when a new one replaces it (e.g., using

AbortController). - Ignore stale responses by checking whether the response still matches the latest inputs.

- Use request IDs / sequence numbers and only accept the newest.

A simple request ID approach:

let latestRequestId = 0;

async function fetchResults(query) {

const requestId = ++latestRequestId;

const res = await fetch(`/api/search?q=${encodeURIComponent(query)}`);

const data = await res.json();

if (requestId !== latestRequestId) return; // stale response

setResults(data);

}

Optimistic updates (and how they go wrong)

Optimistic updates make the UI feel instant: you update the screen before the server confirms. But concurrency can break assumptions:

- The user clicks “Like” twice quickly (like → unlike), but the requests resolve out of order.

- You optimistically decrement inventory, then a later failure forces a rollback—except the user already navigated away or made more changes.

To keep optimism safe, you typically need a clear reconciliation rule: track the pending action, apply server responses in order, and if you must rollback, rollback to a known checkpoint (not “whatever the UI looks like now”).

Performance: When State Changes Are Too Expensive

State updates aren’t “free.” When state changes, the app has to figure out what parts of the screen might be affected and then do the work to reflect the new reality: re-calculating values, re-rendering UI, re-running formatting logic, and sometimes re-fetching or re-validating data. If that chain reaction is bigger than it needs to be, the user feels it as lag, jank, or buttons that seem to “think” before responding.

Why a small change can feel big

A single toggle can accidentally trigger a lot of extra work:

- Large sections of the UI re-render even though only one small piece actually changed.

- Lists re-draw and re-measure, causing scrolling to stutter.

- Objects and arrays get recreated on every update (“deep churn”), so the app can’t easily tell what’s truly different.

The outcome isn’t just technical—it’s experiential: typing feels delayed, animations hitch, and the interface loses that “snappy” quality people associate with polished products.

Common performance traps

One of the most common causes is state that’s too broad: a “big bucket” object holding lots of unrelated information. Updating any field makes the whole bucket look new, so more of the UI wakes up than necessary.

Another trap is storing computed values in state and updating them manually. That often creates extra updates (and extra UI work) just to keep everything in sync.

Tactics that keep the UI fast

Split state into smaller slices. Keep unrelated concerns separate so changing a search input doesn’t refresh an entire page of results.

Normalize data. Instead of storing the same item in many places, store it once and reference it. This reduces repeated updates and prevents “change storms” where one edit forces many copies to be rewritten.

Memoize derived values. If a value can be calculated from other state (like filtered results), cache that calculation so it only re-computes when the inputs actually change.

The goal: fewer stalls, fewer surprises

Good performance-minded state management is mostly about containment: updates should affect the smallest possible area, and expensive work should happen only when it truly needs to. When that’s true, users stop noticing the framework and start trusting the interface.

Debugging and Testing State Without Guesswork

State bugs often feel personal: the UI is “wrong,” but you can’t answer the simplest question—who changed this value and when? If a number flips, a banner disappears, or a button disables itself, you need a timeline, not a hunch.

Make changes traceable (not mysterious)

The fastest path to clarity is a predictable update flow. Whether you use reducers, events, or a store, aim for a pattern where:

- Changes happen through a small set of well-named actions (not random mutations)

- Each action has a clear payload (

setShippingMethod('express'), notupdateStuff) - You can log actions and resulting state transitions consistently

Clear action logging turns debugging from “stare at the screen” into “follow the receipt.” Even simple console logs (action name + key fields) beat trying to reconstruct what happened from symptoms.

Test the logic where it’s stable

Don’t try to test every re-render. Instead, test the parts that should behave like pure logic:

- Unit test reducers / state updaters: given previous state + action, assert next state

- Unit test selectors / derived calculations: given state, assert computed output

- Integration test key user flows: login → load data → edit → save → see confirmation

This mix catches both “math bugs” and real-world wiring issues.

Add lightweight instrumentation for async bugs

Async problems hide in gaps. Add minimal metadata that makes timelines visible:

- timestamps on important updates

- request IDs (attach the ID to actions and responses)

Then when a late response overwrites a newer one, you can prove it immediately—and fix it with confidence.

Picking a State Management Approach (Without Tool Wars)

Build Full Stack Quickly

Generate a frontend plus Go and PostgreSQL backend and test real async behavior early.

Choosing a state tool is easier when you treat it as an outcome of design decisions, not the starting point. Before comparing libraries, map your state boundaries: what is purely local to a component, what needs to be shared, and what is actually “server data” that you fetch and synchronize.

Selection criteria that matter

A practical way to decide is to look at a few constraints:

- App size and lifetime: a small internal tool can stay simple; a long-lived product benefits from stronger conventions.

- Team habits: pick something your team can use consistently (and review confidently).

- Async needs: heavy fetching, caching, pagination, and mutations change the equation.

- State complexity: cross-page workflows, undo/redo, and multi-step forms often require more structure.

A high-level comparison (no ideology)

- Context + hooks: great for dependency injection and low-frequency shared values (theme, auth info). It can work for state, but frequent updates can get noisy without extra patterns.

- Redux-style stores: strong conventions, predictable updates, and great tooling. Best when you need a clear audit trail or complex coordination across features.

- Atom stores (fine-grained state): ergonomic for shared state without wiring lots of reducers. Often easier to scale incrementally.

- Query caches (server-state tools): specialized for fetching, caching, deduping, background refetching, and mutations. They reduce a huge class of “async glue code.”

Avoid tool-first thinking

If you start with “we use X everywhere,” you’ll store the wrong things in the wrong place. Start with ownership: who updates this value, who reads it, and what should happen when it changes.

Combining tools is often the best option

Many apps do well with a server-state library for API data plus a small UI-state solution for client-only concerns like modals, filters, or draft form values. The goal is clarity: each type of state lives where it’s easiest to reason about.

Where Koder.ai fits in

If you’re iterating on state boundaries and async flows, Koder.ai can speed up the “try it, observe it, refine it” loop. Because it generates React frontends (and Go + PostgreSQL backends) from chat with an agent-based workflow, you can prototype alternative ownership models (local vs global, server cache vs UI drafts) quickly, then keep the version that stays predictable.

Two practical features help when experimenting with state: Planning Mode (to outline the state model before building) and snapshots + rollback (to safely test refactors like “remove derived state” or “introduce request IDs” without losing a working baseline).

A Practical Checklist to Make State Less Painful

State gets easier when you treat it like a design problem: decide who owns it, what it represents, and how it changes. Use this checklist when a component starts feeling “mysterious.”

1) Clarify ownership and the single source of truth

Ask: Which part of the app is responsible for this data? Put state as close as possible to where it’s used, and lift it up only when multiple parts truly need it.

- One owner per piece of state.

- Pass data down; send changes up via callbacks/events.

- If two places can update the same value, you don’t have a source of truth—you have a conflict waiting to happen.

2) Avoid duplication and model derived values

If you can compute something from other state, don’t store it.

- Store the minimal inputs (e.g.,

items,filterText). - Compute outputs (e.g.,

visibleItems) during render or via memoization.

3) Make async states explicit (not implied)

Async work is clearer when you model it directly:

- Prefer a small “request state” shape:

status: 'idle' | 'loading' | 'success' | 'error', plusdataanderror. - Treat “loading” and “error” as first-class UI states, not scattered booleans.

4) Watch for common anti-patterns

- Copying props to state “just in case” (creates drift).

- Globalizing everything (makes unrelated screens coupled).

- Boolean soup (

isLoading,isFetching,isSaving,hasLoaded, …) instead of a single status.

5) Refactor with small, safe steps

- Split mixed state: separate UI concerns (open/closed, input text) from server data.

- Delete stored derived values and compute them from the real source.

- Centralize side effects (fetching, subscriptions) in one place per feature.

Practical goals

Aim for fewer “how did it get into this state?” bugs, changes that don’t require touching five files, and a mental model where you can point to one place and say: this is where the truth lives.