Sep 09, 2025·8 min

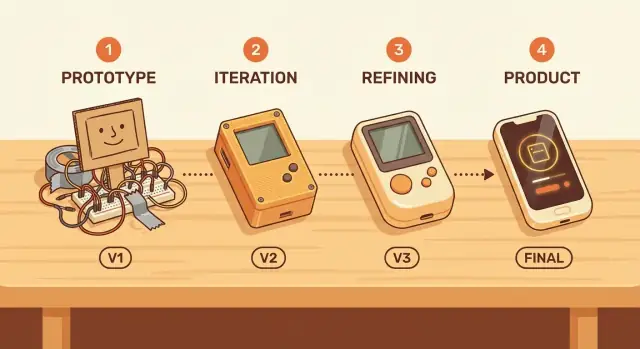

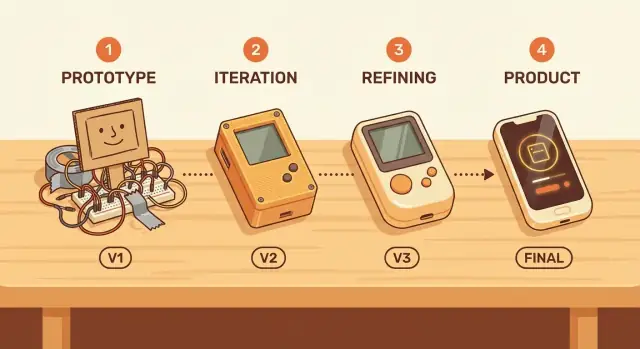

Why Many Successful Products Start as Rough First Versions

Many great products began as imperfect first releases. Learn why rough starts help teams learn faster, reduce risk, and build what users truly want.

Many great products began as imperfect first releases. Learn why rough starts help teams learn faster, reduce risk, and build what users truly want.

A “rough first version” isn’t the same as careless quality. It’s a product that works well enough to be tried by real people, but still has missing features, clunky workflows, and plenty of room to improve. The difference is intent: rough means focused and limited; careless means unreliable and unsafe.

Perfection is rare at the start because most of what “perfect” means is unknown until users interact with the product. Teams can guess which features matter, what wording makes sense, or where people will get stuck—but guesses are often wrong. Even experienced builders regularly discover that the real problem customers want solved is slightly different than what was imagined.

The point of an imperfect start is learning, not lowering standards. A good rough first version still respects the user:

When teams adopt a learn-first mindset, they stop treating the first release as a final exam and start treating it as a field test. That shift makes it easier to narrow scope, release earlier, and improve based on evidence instead of opinions.

In the next sections, you’ll see practical examples—like MVP-style releases and early adopter programs—and guardrails to avoid common mistakes (for example: how to draw a hard line between “imperfect” and “unusable,” and how to capture feedback without getting pulled into endless custom requests).

Early in a product’s life, confidence is often an illusion. Teams can write detailed specs and roadmaps, but the biggest questions can’t be answered from a conference room.

Before real users touch your product, you’re guessing about:

You can research all of these, but you can’t confirm them without usage.

Traditional planning assumes you can predict needs, prioritize features, then build toward a known destination. Early-stage products are full of unknowns, so the plan is built on assumptions. When those assumptions are wrong, you don’t just miss a deadline—you build the wrong thing efficiently.

That’s why early releases matter: they turn debates into evidence. Usage data, support tickets, churn, activation rates, and even “we tried it and stopped” are signals that clarify what’s real.

A long list of enhancements can feel customer-focused, but it often contains buried bets:

Build these too early and you’re committing to assumptions before you’ve validated them.

Validated learning means the goal of an early version isn’t to look finished—it’s to reduce uncertainty. A rough first version is successful if it teaches you something measurable about user behavior, value, and willingness to continue.

That learning becomes the foundation for the next iteration—one based on evidence, not hope.

Teams often treat progress as “more features shipped.” But early on, the goal isn’t to build fast—it’s to learn fast. A rough first version that reaches real users turns assumptions into evidence.

When you ship early, feedback loops shrink from months to days. Instead of debating what users might do, you see what they actually do.

A common pattern:

That speed compounds. Every short cycle removes uncertainty and prevents “building the wrong thing really well.”

“Learning” isn’t a vague feeling. Even simple products can track signals that show whether the idea works:

These metrics do more than validate. They point to the next improvement with higher confidence than internal opinions.

Speed doesn’t mean ignoring safety or trust. Early releases must still protect users from harm:

Build for learning first—while keeping users safe—and your rough first version becomes a purposeful step, not a gamble.

An MVP (minimum viable product) is the smallest version of your product that can test whether a key promise is valuable to real people. It’s not “the first version of everything.” It’s the shortest path to answering one high-stakes question like: Will anyone use this? Pay for it? Change their routine for it?

An MVP is a focused experiment you can ship, learn from, and improve.

An MVP is not:

The goal is viable: the experience should work end-to-end for a narrow set of users, even if the scope is small.

Different products can test the same value in different forms:

MVP scope should match your biggest uncertainty. If the risk is demand, prioritize testing real usage and payment signals. If the risk is outcomes, focus on proving you can reliably deliver results—even if the process is manual.

One practical way to support this approach is to use a build-and-iterate workflow that minimizes setup cost. For example, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai lets you prototype web, backend, or mobile apps via chat, then export source code and deploy—useful when you want a real, end-to-end MVP without committing to a long engineering cycle before you’ve validated the core promise.

A rough first version can still be a great start—if it helps a specific person get a specific job done. “Good enough” isn’t a universal standard; it depends on the user’s job-to-be-done. A prototype-to-product journey works best when you define that job clearly (for example: “send an invoice in under two minutes” or “share a file securely with one link”).

An imperfect start is allowed to be small and a bit awkward. It’s not allowed to be unreliable at the one thing it promises.

A practical minimum quality bar for an MVP:

If the core flow breaks, early adopters can’t give useful feedback—because they never reach the moment where the product delivers value.

“Shipping fast” often goes wrong when teams cut the wrong things. Cutting extra features is fine; cutting clarity is not. A minimum viable product should prefer:

This makes iteration faster because feedback is about what matters, not confusion.

Even in an early release, accessibility and basic performance shouldn’t be treated as “nice-to-haves.” If text can’t be read, actions can’t be completed with a keyboard, or pages take too long to load, you’re not testing product-market fit—you’re testing people’s patience. Continuous improvement starts with a baseline that respects users’ time and needs.

Product-market fit (PMF) is best defined in plain terms: users would genuinely miss your product if it disappeared. Not “they like the idea,” not “they clicked the announcement,” but real dependence—something they’ve folded into their routine.

Teams are biased toward their own assumptions. You know the roadmap, you understand the edge cases, and you can imagine all the future value. But customers don’t buy your intention—they experience what exists today.

Internal opinions also suffer from “sample size = people like us.” Colleagues, friends, and early testers often share your context. Real usage introduces the messy constraints you can’t simulate: time pressure, competing alternatives, and zero patience for confusing flows.

Look for behavior that suggests the product is solving a recurring problem:

Early numbers can mislead. Be cautious with:

A rough first version is valuable because it gets you to these reality checks quickly. PMF isn’t a meeting outcome—it’s a pattern you observe once real users put the product to work.

Early adopters don’t tolerate rough edges because they enjoy glitches—they do it because the benefit is unusually high for them. They’re the people with a sharp, frequent problem, who are actively looking for a workaround. If your rough first version removes a major pain point (even imperfectly), they’ll trade polish for progress.

Early adopters are often:

When the “before” is painful enough, a half-finished “after” still feels like a win.

Look for places where the pain is already being discussed: niche Slack/Discord groups, subreddits, industry forums, and professional communities. Another reliable signal: people who have built their own hacks (templates, scripts, Notion boards) to manage the problem—they’re telling you they need a better tool.

Also consider “adjacent” niches—smaller segments with the same core job-to-be-done but fewer requirements. They can be easier to serve first.

Be explicit about what’s included and what’s not: what the product can do today, what’s experimental, what’s missing, and the kinds of issues users might hit. Clear expectations prevent disappointment and increase trust.

Make feedback simple and immediate: a short in-app prompt, a reply-to email address, and a few scheduled calls with active users. Ask for specifics: what they tried to do, where they got stuck, and what they did instead. That detail turns early usage into a focused roadmap.

Constraints get a bad reputation, but they often force the clearest thinking. When time, budget, or team size is limited, you can’t “solve” uncertainty by piling on features. You have to decide what matters most, define what success looks like, and ship something that proves (or disproves) the core value.

A tight constraint acts like a filter: if a feature doesn’t help validate the main promise, it waits. That’s how you end up with simple, clear solutions—because the product is built around one job it does well, not ten jobs it does poorly.

This is especially useful early on, when you’re still guessing what users truly want. The more you constrain scope, the easier it is to connect an outcome to a change.

Adding “nice-to-haves” can mask the real problem: the value proposition isn’t sharp yet. If users aren’t excited by the simplest version, more features rarely fix that—they just add noise. A feature-rich product can feel busy while still failing to answer the basic question: “Why should I use this?”

A few constraint-friendly ways to test the riskiest idea:

Treat “no” as a product skill. Say no to features that don’t support the current hypothesis, no to extra user segments before one segment is working, and no to polish that doesn’t change decisions. Constraints make those “no’s” easier—and they keep your early product honest about what it really delivers.

Overbuilding happens when a team treats the first release like the final verdict. Instead of testing the core idea, the product becomes a bundle of “nice-to-haves” that feel safer than a clear yes/no experiment.

Fear is the biggest driver: fear of negative feedback, fear of looking unprofessional, fear that a competitor will appear more polished.

Comparison adds fuel. If you benchmark yourself against mature products, it’s easy to copy their feature set without noticing they earned those features through years of real usage.

Internal politics can push things further. Extra features become a way to satisfy multiple stakeholders at once (“add this so Sales can pitch it,” “add that so Support won’t complain”), even if none of it proves the product will be wanted.

The more you build, the harder it becomes to change direction. That’s the sunk cost effect: once time, money, and pride are invested, teams defend decisions that should be revisited.

Overbuilt versions create expensive commitments—complex code, heavier onboarding, more edge cases, more documentation, more meetings to coordinate. Then even obvious improvements feel risky because they threaten all that investment.

A rough first version limits your options in a good way. By keeping scope small, you learn earlier whether the idea is valuable, and you avoid polishing features that won’t matter.

A simple rule helps:

Build the smallest thing that answers one question.

Examples of “one question”:

If your “MVP” can’t clearly answer a question, it’s probably not minimal—it’s just early-stage overbuilding.

Shipping early is useful, but it’s not free. A rough first version can create real damage if you ignore the risks.

The biggest risks usually fall into four buckets:

You can reduce harm without slowing to a crawl:

If you’re using a platform to ship quickly, look for safety features that support early iteration. For instance, Koder.ai includes snapshots and rollback (so you can recover from a bad release) and supports deployment/hosting—helpful when you want to move fast without turning every change into a high-stakes event.

Instead of releasing to everyone at once, do a staged rollout: 5% of users first, then 25%, then 100% as you gain confidence.

A feature flag is a simple switch that lets you turn a new feature on or off without redeploying everything. If something breaks, you flip it off and keep the rest of the product running.

Don’t “test in production” when the stakes are high: safety-related features, legal/compliance requirements, payments or sensitive personal data, or anything needing critical reliability (e.g., medical, emergency, core finance). In those cases, validate with prototypes, internal testing, and controlled pilots before public use.

Shipping a rough first version is only useful if you turn real reactions into better decisions. The goal isn’t “more feedback”—it’s a steady learning loop that makes the product clearer, faster, and easier to use.

Start with a few signals that reflect whether people are actually getting value:

These metrics help you separate “people are curious” from “people are succeeding.”

Numbers tell you what happened. Qualitative feedback tells you why.

Use a mix of:

Capture exact phrases users use. Those words are fuel for better onboarding, clearer buttons, and simpler pricing pages.

Don’t make a to-do list of every request. Group input into themes, then prioritize by impact (how much it improves activation/retention) and effort (how hard it is to deliver). A small fix that removes a major point of confusion often beats a big new feature.

Link learning to a regular release rhythm—weekly or biweekly updates—so users see progress and you keep reducing uncertainty with each iteration.

A rough first version works when it’s intentionally rough: focused on proving (or disproving) one key bet, while still being trustworthy enough that real people will try it.

Write one sentence that explains the job your product will do for a user.

Examples:

If your MVP can’t clearly keep that promise, it’s not ready—no matter how polished the UI is.

Decide what must be true for users to trust the experience.

Checklist:

Reduce scope until you can ship quickly without weakening the test. A good rule: cut features that don’t change the decision you’ll make after launch.

Ask:

If your bottleneck is implementation speed, consider a toolchain that shortens the path from idea → working software. For example, Koder.ai can generate a React web app, a Go + PostgreSQL backend, or a Flutter mobile app from a chat-driven spec, then let you export the code when you’re ready to own the repo—useful for getting to a real user test faster.

Ship to a small, specific group, then collect feedback in two channels:

Take five minutes today: write your core promise, list your quality bar, and circle the single riskiest assumption. Then cut your MVP scope until it can test that assumption in the next 2–3 weeks.

If you want more templates and examples, browse related posts in /blog.

A rough first version is intentionally limited: it works end-to-end for one clear job, but still has missing features and awkward edges.

“Careless” quality is different—it’s unreliable, unsafe, or dishonest about what it can do.

Early on, the biggest inputs are still unknown until people use the product: real workflows, who the motivated users are, what language makes sense, and what they’ll actually pay for.

Shipping a small real version turns assumptions into evidence you can act on.

Set a minimum bar around the core promise:

Cut features, not reliability or clarity.

An MVP is the smallest viable experiment that tests a high-stakes assumption (demand, willingness to pay, or whether users will change behavior).

It’s not a glossy demo, and it’s not a half-broken product—it should still deliver the promised outcome for a narrow use case.

Common shapes include:

Pick the one that answers your riskiest question fastest.

Start with signals tied to real value, not attention:

Use a small set so you can make decisions quickly.

Early adopters feel the problem more sharply and often already use clunky workarounds (spreadsheets, scripts, manual checks).

Find them where the pain is discussed (niche communities, forums, Slack/Discord), and set expectations clearly that it’s a beta/preview so they opt in knowingly.

Reduce risk without waiting for perfection:

These protect trust while still keeping feedback loops short.

A staged rollout releases changes to a small percentage first (e.g., 5% → 25% → 100%) so you can catch issues before everyone hits them.

A feature flag is an on/off switch for a feature, letting you disable it quickly without redeploying the entire product.

Don’t ship early when failure could cause serious harm or irreversible damage—especially with:

In these cases, validate with prototypes, internal testing, and controlled pilots first.