May 03, 2025·8 min

Why Workday Gets Sticky: Compliance, Data Models, Process Lock-In

See why Workday becomes hard to replace: compliance needs, shared HR/finance data models, approvals, reporting, and integrations that create real switching costs.

See why Workday becomes hard to replace: compliance needs, shared HR/finance data models, approvals, reporting, and integrations that create real switching costs.

“Workday stickiness” usually isn’t about a contract that traps you. It’s about the way a system becomes woven into day-to-day operations until changing it would mean changing how people, data, and decisions move through the company.

Stickiness is when a platform becomes the default home for critical work because it’s trusted, integrated, and embedded in routines.

Lock-in is when leaving becomes expensive or risky—because too many processes, controls, and dependencies assume that platform’s structure.

Most organizations experience both. Stickiness is often a positive outcome of standardization and consistency. Lock-in shows up the moment you seriously consider replacing the system.

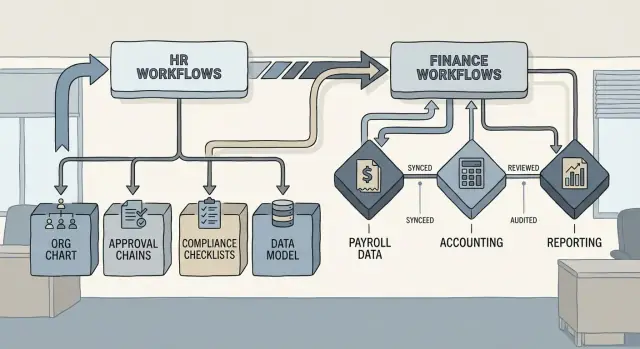

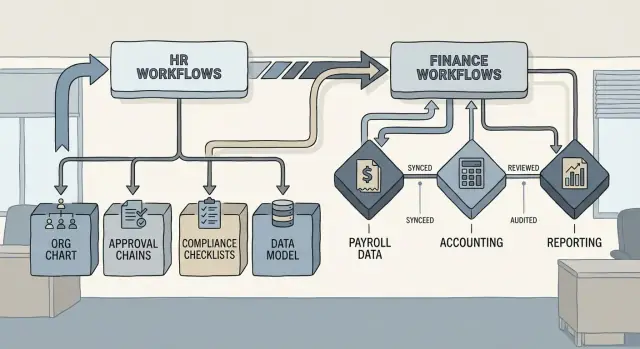

A point tool can often be swapped if it affects one team and a narrow workflow. An HR and finance platform is different because it touches:

When one platform sits in the middle of hiring, payroll, time tracking, expenses, procurement, and financial close, it becomes the shared “operating system” for many teams. Replacing it isn’t just an IT project—it’s coordinated change across HR, finance, and the business.

This article takes a practical, non-technical view of why replacement gets complicated. The main forces are:

If you’re considering expanding your Workday footprint—or questioning whether you should—understanding these three forces clarifies where the real switching costs come from and how to manage them.

Workday gets “sticky” fastest when it stops being an HR tool and becomes the shared platform for both people and money. That shift is usually driven by a cluster of anchoring modules—most commonly HCM, Payroll, Financial Management, and Planning (often Adaptive Planning). Each module is useful on its own; together they create a compounding effect that’s hard to unwind.

Once HCM holds your employee records, downstream systems start treating those records as the canonical truth. Payroll depends on the same worker data (jobs, pay, tax location). Finance depends on the same organizational structure (cost centers, managers, worktags). Planning depends on both to forecast headcount costs.

A simple example: if a department changes its structure, HCM updates reporting lines, Finance updates cost allocations, Payroll updates earning and deduction handling, and Planning updates budgets—all referencing shared definitions. Moving one piece means you must rebuild the connections everywhere else.

This platform effect isn’t only technical. Ownership becomes cross-functional: HR owns worker lifecycle processes, Finance owns accounting structures and controls, Payroll owns statutory execution, and FP&A owns forecasts. As each group customizes “their” part, dependencies spread across teams, timelines, and governance.

The deepest lock-in happens when Workday becomes the system of record for:

At that point, switching isn’t just replacing software—you’re re-defining how the business agrees on who people are, where they sit, and how money follows them.

Compliance is one of the quickest ways an HR–finance system stops being “just software” and becomes part of your operating rules. Teams usually start with a straightforward goal—pay people correctly and close the books on time—but the pressure expands as regulations, audits, and internal controls mature.

Common requirements include tax and payroll rules (multi-state, multi-country, local filings), labor and employment regulations (leave rules, overtime, works councils), SOX-style financial controls, and privacy obligations like GDPR/CCPA. Each one adds a “must not fail” expectation to how data is captured, approved, stored, and reported.

To satisfy those expectations, organizations encode policies directly into Workday configuration: eligibility rules, validation logic, effective-dating behavior, approval chains, and role-based access. For example, a policy about who can change a job profile becomes a workflow with step conditions, delegated approvers, and compensating controls.

Over time, these choices harden because changing them isn’t only a functional decision—it can trigger payroll re-testing, controls re-validation, and re-training across the business.

Auditors don’t just ask “Is it correct?” They ask for evidence: who approved what, when, under which policy, using which source data. That drives detailed audit trails, segregation of duties, and consistent transaction patterns. Once reporting and evidence expectations are established, deviations become risks.

Annual audits, quarterly controls testing, and periodic privacy reviews create a cycle where “known-good” processes are repeated and protected. The safest option becomes keeping configuration stable—even when the business changes—because stability is easier to defend than constant process churn.

A “data model” is the set of fields you store (like Job Profile or Cost Center), how those fields relate to each other (who links to what), and the rules that keep them consistent (what’s required, what’s allowed, what triggers downstream actions).

In Workday, these definitions aren’t just database choices—they become the shared language HR, Finance, IT, and auditors rely on.

Consider a common chain:

That’s not just reporting. It often drives payroll costing, budget checks, approvals, and accounting entries.

When you change a definition—rename cost centers, split one cost center into three, or redefine how positions map to accounts—you don’t just “update a field.” You potentially break:

Even small adjustments can cause “silent” errors: transactions still flow, but land in the wrong place or skip an expected control.

This is why master data governance matters: clear ownership of key objects (cost centers, companies, job profiles), change approval workflows, naming standards, and a habit of impact analysis before updates.

A practical tip: when governance relies on tribal knowledge, teams often build side tools (intake forms, approval dashboards, integration inventories) to keep changes predictable. A vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can help internal teams spin up those lightweight workflow and tracking apps quickly—without waiting for a full software project—while still being able to export source code and host under a custom domain.

Workday security isn’t just a set of technical permissions—it reflects how your organization is structured. HR partners need access to worker data, finance teams need access to transactions and approvals, managers need visibility into their teams, and auditors need read-only evidence without being able to change anything. Once those roles are mapped, tested, and trusted, they become part of “how work gets done,” which is one reason Workday becomes hard to replace.

Most companies end up with a layered model: broad role families (HR, finance, managers, payroll, procurement) and then narrower assignments (by region, business unit, cost center, company, or supervisory org). That structure is convenient—until it’s deeply embedded.

The more precisely you mirror the org chart in security, the more security depends on organizational design decisions, and the more org changes create access work.

Least-privilege access sounds straightforward: give people only what they need. In practice, it requires careful design and repeated testing because the “need” is often conditional:

The testing burden is part of the stickiness. You’re not only validating that people can do their jobs—you’re also proving that they can’t do things they shouldn’t.

In finance especially, segregation of duties (SoD) is a core requirement: the person who creates a vendor shouldn’t also approve payments; the person who initiates an expense shouldn’t be the final approver; payroll changes should be separated from payroll processing. These controls are often audited, meaning “good enough” is rarely acceptable.

A single security change can affect business processes end-to-end: who can initiate, approve, rescind, correct, or view a transaction. It can also change what appears in reports and dashboards, because reporting frequently respects the same security boundaries.

That ripple effect makes teams cautious about change—and increases the switching costs of moving away from a proven model.

Workday gets “sticky” not because one feature is hard to copy, but because daily work gets threaded into a single, end-to-end path. Once that path is running, changing systems means re-building not just screens and fields, but the way people coordinate.

A common chain looks like:

Hire → compensation → payroll → GL posting.

At the start, HR enters the worker, job, location, and dates. That triggers downstream rules: eligibility, comp bands, benefit start dates, costing allocations, and pay group selection. Payroll then depends on those upstream choices being consistent, and Finance expects results to land in the right accounts and cost centers.

The “lock” is the accumulation of small controls that feel reasonable on their own:

Over time, those steps become the organization’s version of “how we do things.” People stop thinking of them as Workday steps and start treating them as policy.

Once workflows are reliable, teams plan around them: deadlines are set based on approval queues, managers learn which requests get rejected, and HR creates checklists that mirror Workday tasks. Informal behaviors shift too—who escalates what, when “off-cycle” changes are allowed, and which reports are treated as the source of truth.

That’s why replacement is more than migration. You’re asking the business to unlearn routines that reduce risk and keep pay and accounting accurate.

A new platform can replicate outcomes, but it still forces re-work: rewriting SOPs, updating audit evidence, retraining managers on approvals, and coaching power users on new exception paths. The effort isn’t only technical; it’s a change management program that touches nearly every role involved in the employee lifecycle and financial close.

Reporting is where stickiness becomes visible to everyone. A system can be tolerated even if it’s clunky—until executives expect consistent numbers every week, and the organization can’t agree on what those numbers mean.

Workday reporting depends on shared definitions: what counts as headcount, who is active, how FTE is calculated, when a worker is considered terminated, and which cost center hierarchy is “official.” Once those definitions are embedded in calculated fields, report prompts, and security rules, they become the organization’s working contract.

Changing platforms isn’t just moving data; it’s renegotiating those definitions across HR, Finance, and Operations—often while still needing to publish the same outputs on the same cadence.

Executive dashboards and board packs quickly turn into non-negotiable outputs. Leaders don’t want a new story—they want the same KPIs, refreshed on schedule, with explanations that match prior periods.

That pressure typically pushes teams to preserve Workday’s reporting structure, because it already aligns to how the business “talks” about workforce cost, hiring velocity, attrition, and budget vs. actuals.

Analytics rarely focuses on today’s snapshot alone. It depends on time-series history:

If a replacement system can’t reproduce history at the same granularity—or can’t explain discrepancies—trust in reporting erodes quickly.

Custom reports often start as “one-offs” for a VP or a monthly close task. Over time they become mission-critical artifacts: tied to incentives, compliance evidence, workforce planning, and recurring leadership meetings.

Even when documentation is thin, the output becomes the standard—making Workday harder to replace than the underlying transactions.

Workday rarely stands alone for long. As soon as it goes live, teams connect it to the rest of the company’s systems—and each connection quietly adds switching costs.

Most organizations end up with a mix of:

Individually, each integration looks manageable. Together, they form a dependency network that’s hard to fully inventory—especially when a feed was built years ago and “still works.”

Many Workday integrations contain business rules, not just mappings. Examples include how you translate job changes into payroll actions, how you calculate costing splits, how you decide which worker populations trigger benefit eligibility, or how you transform organizational structures into access groups.

Those rules are often scattered across:

When you replace Workday, you’re not only rebuilding pipes—you’re rediscovering and re-implementing policy.

Teams may use Workday exports as “source of truth” for headcount reporting, finance actuals, identity provisioning, IT asset assignments, background checks, or union and compliance reporting. Over time, spreadsheets, scripts, and dashboards start assuming Workday’s field definitions and timing.

If you’re considering major change, start by documenting integrations as products: owners, SLAs, transformations, and consumers. A structured approach (and a checklist) helps—see /blog/hris-migration-checklist.

Workday doesn’t just run today’s HR and finance transactions—it becomes the system of record for “what happened” across years of employees, org changes, pay decisions, and accounting outcomes.

That history is hard to give up because audits, benefits disputes, and month/quarter close often hinge on being able to trace a result back to the original records, approvals, and effective dates.

Historical records are frequently needed to answer practical questions: What was an employee’s eligibility on a specific date? Which job profile and cost center was in effect when a payment was posted? Why did a balance or headcount number shift between two closes?

When Workday holds those timelines (not just current values), it becomes the “court transcript” that people trust.

Legacy data is rarely clean. You may find duplicates (two worker IDs for one person), missing fields (no hire reason or FTE), inconsistent effective dates, and structures that changed over time (job families redesigned, cost centers re-numbered, pay components renamed).

Even when data exists, it might not align with how the new system expects to represent it.

A realistic migration includes:

Regulatory and policy retention requirements can force you to keep access to legacy data long after cutover. If you don’t migrate everything, you’ll still need a plan for secure, searchable access—plus clear guidance on which system is authoritative for which time period.

Workday doesn’t just sit in the background as “software.” Over time, it becomes a managed operating model: who can request changes, who approves them, how releases are planned, and what “good” looks like.

That operational layer is a major reason Workday gets sticky—even when teams complain about limitations.

Early decisions (job profiles, supervisory orgs, costing rules, security groups, approval chains) often start as configuration choices made during implementation. A year later, those choices are treated as policy.

People stop asking, “Is this the best process?” and start asking, “How do we make Workday do it?” That shift is subtle, but it hardens the system into the organization’s default way of working.

As soon as Workday is tied to payroll, close, audits, and compliance, governance becomes formal:

This is sensible control, but it also creates inertia. When change requires a ticket, a review board, test scripts, and a release calendar, “leave it as-is” becomes the easiest option.

Many organizations build an internal HRIS/Workday Center of Excellence. Over time, that team accumulates deep knowledge of edge cases, workarounds, and historical decisions—knowledge that isn’t easily transferable to another platform.

Documentation libraries, training decks, enablement videos, and internal playbooks become valuable assets. The catch: they’re tightly aligned to Workday’s screens, roles, and terminology, so migrating isn’t just moving data—it’s rewriting how people learn and execute work.

Workday’s stickiness isn’t automatically a bad thing. Some of it is healthy standardization: shared definitions, consistent approvals, and a single source of truth that makes audits easier and decisions faster.

The goal is repeatable execution—not freezing the business in place.

Stickiness helps when it reduces ambiguity and rework. Examples include consistent job/position structures, clean cost center hierarchies, and standardized onboarding or close processes that people actually follow.

If teams spend less time debating “which data is right” and more time acting on it, that’s productive stickiness.

Stickiness hurts when the system becomes the reason work slows down. Watch for warning signs:

Customization can feel like progress—until it increases switching costs and upgrade pain. The more you build one-off rules, special workflows, and bespoke reports, the more effort it takes to test releases, retrain users, and explain exceptions to auditors.

Over time, you’re not just operating Workday—you’re operating your unique version of it.

Ask: does this change improve control, speed, or clarity?

If it doesn’t clearly strengthen at least one of those, you’re likely adding friction that will be expensive to unwind later.

Expanding Workday’s footprint (more countries, more modules, more workflows) can pay off—but it also increases switching costs. Before you add scope, take a few steps that keep your options open without slowing progress.

Document what would be hard to unwind later. A simple spreadsheet is enough—as long as it’s maintained.

Include:

The goal isn’t to scare anyone—it’s to make dependencies visible so you can design around them.

You don’t need a “rip-and-replace plan” to be smart about exit risk.

If your teams keep these artifacts in scattered docs and spreadsheets, consider consolidating them into a simple internal app (integration catalog, data dictionary, control checklist). Tools like Koder.ai are designed for building that kind of internal software quickly via chat—useful when you want lightweight governance tooling without a long development cycle.

Ask vendors and internal stakeholders:

If you’re evaluating how much to standardize versus customize, you can compare options at /pricing and browse related posts at /blog.

It’s hard to replace because it becomes the shared operating layer for people, money, controls, and reporting. Once hiring, payroll, close, and planning all depend on the same definitions and workflows, replacement turns into coordinated change across HR, Finance, Payroll, IT, and audit—not just a software swap.

Stickiness means teams choose to stay because the platform is trusted, integrated, and embedded in routines.

Lock-in means leaving is risky or expensive because controls, data definitions, integrations, and audit expectations assume the current system’s structure.

Most organizations experience both at the same time.

Because HR + finance platforms sit at the center of end-to-end flows like hire-to-pay, procure-to-pay, and record-to-report.

Replacing a point tool might affect one team. Replacing a core HR/finance platform forces you to rebuild shared structures (orgs, cost centers, security roles) and re-align multiple departments on timing, approvals, and definitions.

HCM, Payroll, Financials, and Planning reinforce each other by sharing “canonical” objects like worker records, org structures, and costing.

A change in one area (like a reorg) can cascade into:

Compliance requirements get encoded into configuration: approval chains, validations, effective-dating behavior, role assignments, and audit trails.

Once auditors and regulators accept a “known-good” process, changing it often means re-testing controls, re-validating payroll/close outcomes, and re-training users—so teams avoid change unless the benefit is clear.

Because it becomes the shared language that connects teams and systems.

When objects like Worker → Position → Cost Center → Ledger Account drive costing, budget checks, approvals, and GL entries, changing definitions can break reports, integrations, and controls—or cause silent mis-postings that are harder to detect than a hard failure.

Workday security is tied to how your organization operates: who initiates, who approves, who can view sensitive data, and what auditors can review.

Security changes can ripple into workflows and reporting, and finance-specific requirements like segregation of duties (SoD) often create non-negotiable role designs that take time to replicate and re-prove in a new system.

Lock-in forms in the accumulated details: approvals, validations, handoffs, and exception paths that become “muscle memory.”

Even if another platform can reproduce outcomes, you still must redo the operational layer:

Because executives expect the same KPIs on the same cadence, with consistent definitions over time (headcount, FTE, attrition, budget vs. actuals).

If a replacement system can’t reproduce time-series history and explain discrepancies with comparable auditability, trust erodes quickly—even if the new tool is technically capable.

Start with a practical “lock-in map” you keep current:

Then reduce future switching costs by standardizing definitions outside any one vendor and using reusable integration patterns (prefer API-first; minimize hard-coded transforms).