Oct 26, 2025·8 min

YC Lessons: Why the Best Startups Start Small and Boring

Y Combinator-style lessons on building momentum: start with a narrow, almost boring idea, win a tiny market, then expand with evidence—not hype.

Y Combinator-style lessons on building momentum: start with a narrow, almost boring idea, win a tiny market, then expand with evidence—not hype.

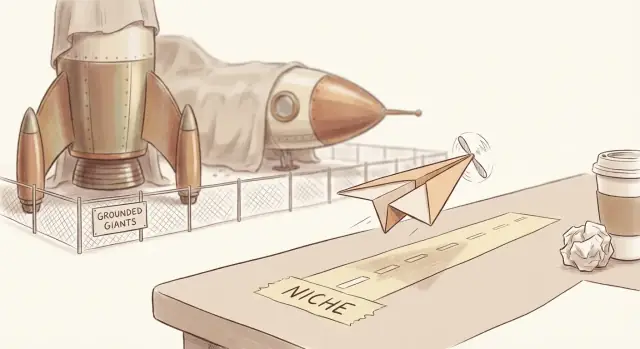

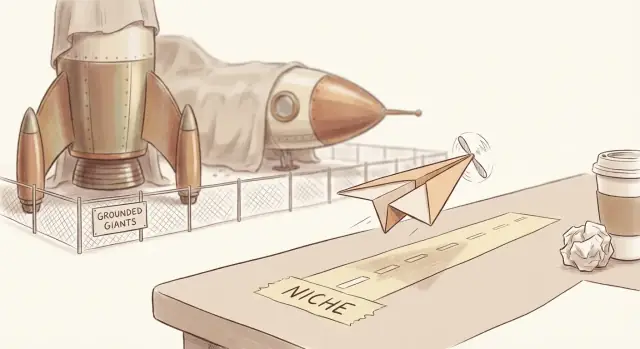

Y Combinator’s “start small” advice is easy to misread as “think small.” That’s not the point. “Small” is about scope—what you build first, who it’s for, and what promise you can reliably keep—while ambition can stay huge.

Starting small means choosing an initial version of your company that can actually work. A smaller scope lets you ship, learn, and improve faster. It also forces clarity: you can’t hide behind a broad mission statement when your first users are counting on one specific outcome.

A startup can aim to become a massive company and still begin with something that looks almost unimpressive: one user type, one workflow, one clear benefit.

Founders often confuse “bigger” with “better” and try to serve everyone with a long feature list. YC’s version of “small” is the opposite:

Vague positioning sounds like: “We help teams be more productive.” Narrow positioning sounds like: “We help independent dental offices reduce no-shows by automatically filling last-minute cancellations.”

A good starting point is a specific user + specific job:

That’s small enough to validate quickly, and focused enough to build something people will pay for.

Starting small isn’t a permanent identity—it’s a sequence. Win a tiny, well-defined slice of the market first. Once you reliably deliver value there, you expand outward with confidence instead of guessing.

A narrow Ideal Customer Profile (ICP) is a simple decision: who exactly is this for, and what situation triggers the need? Not “small businesses” or “teams”—but a specific person with a specific job to do.

Use this format:

It’s for: [role + type of company]

When: [a repeatable moment of pain / deadline / risk]

Example: “It’s for independent CPAs when they’re onboarding a new monthly client and need to collect documents without chasing emails.”

When the ICP is tight, your startup stops guessing.

Messaging becomes straightforward because you can describe one familiar day-in-the-life problem.

Pricing gets simpler because you can anchor to a known budget owner and a clear value metric (per client, per seat, per project).

Product decisions get faster because you’re building for one workflow, not five. You can say “no” without guilt because it’s not for everyone—yet.

Look for:

1) Write a “not for” list (10 minutes). List 5–10 customer types you will not serve in the next 90 days.

2) Pick your top 1–2 customer types. From your conversations, choose the two groups with the sharpest pain and fastest decisions. Commit to one as the default ICP, and treat the other as “later.”

“Boring” is usually shorthand for “I understand it immediately.” That’s not a weakness—it’s a sales advantage.

An “almost boring” startup has three traits: obvious value, a clear buyer, and proven demand. The customer already knows the problem is real, already has budget or urgency, and can picture success without a long explanation.

That clarity speeds up everything: your pitch, your pricing, your roadmap, and your first few customer conversations.

When you pick a familiar pain—missed invoices, compliance checklists, scheduling chaos, churn in subscriptions—you’re not asking the market to learn a new category. You’re offering a better way to solve something they already try to solve.

That means:

Early on, the biggest bottleneck is not engineering—it’s learning. If your idea requires heavy education, you’ll struggle to tell whether people don’t want it or just don’t understand it yet.

Almost-boring ideas reduce that ambiguity. When a prospect says “yes,” you can attribute it to real value, not hype or novelty.

Novel technology can be powerful, but it’s risky when the buyer is undefined. If you can’t answer “who buys this?” and “what budget line does it come from?” you end up building toward applause instead of purchase.

The counterintuitive move is to anchor innovation to a familiar, painful use case—so the market pulls the product out of you, rather than you pushing a new story into the market.

A “big vision” is easy to talk about and hard to buy. Early customers don’t pay for visions—they pay to make an immediate problem go away.

A hair-on-fire problem is:

Strong problems (people actively search, complain, or budget for these):

Weak problems (nice-to-have, unclear owner, no budget):

Urgency shortens sales cycles because the buyer already agrees the problem is real—and they’re motivated to act. It also improves retention: when your product is tied to a recurring pain (missed deadlines, failed compliance checks, revenue leakage), customers keep paying because stopping would reintroduce the problem.

Ask 5–10 target users:

Early on, your biggest advantage isn’t automation—it’s attention. “Do things that don’t scale” means being willing to deliver the product in a hands-on way so you can get real users, real feedback, and real learning before you invest in building the “perfect” system.

For the first 10 customers, you might do manual onboarding over a call, set up their account yourself, import their data, or tailor a workflow to their exact situation.

This can look like concierge support: creating templates for them, writing the first draft (if you’re a writing tool), configuring integrations, or even sending reminders and check-ins. It’s not a permanent operating model—it’s a learning strategy.

When you personally onboard users, you see where they hesitate, what they try to do first, and what they actually value. That helps you:

Start where your ideal customers already gather:

A simple approach: offer a highly specific setup help session in exchange for trying the product for a week.

Keep it ethical: be transparent about what’s manual and what’s product. Document everything you do repeatedly (requests, steps, objections), then turn the top 1–2 repetitive actions into lightweight automation later. The goal is to earn learning and trust now—then scale what works.

A wedge product is the smallest product that completes one job end-to-end for a specific customer. Not a demo. Not a partial workflow. It’s the minimal version that actually delivers the result someone is trying to achieve—and makes them say, “I’d pay for this because it saves me time/money/stress.”

Think “send invoices and get paid” rather than “a finance platform,” or “book 10 qualified sales calls” rather than “a CRM ecosystem.” The wedge is your way into the market: narrow, sharp, and easy to judge.

Early teams often debate feature checklists because it feels safer than committing. Instead, define the outcome first:

If your product doesn’t reliably produce that outcome, adding more features won’t fix the core problem.

A simple rule: must-have features are the ones required to deliver the promised outcome without workarounds.

Nice-to-have features are everything else—even if competitors have them.

A practical test: if you removed a feature, would the customer still get the outcome with similar effort and confidence? If yes, it’s not must-have (yet).

“Platform first” thinking pushes you to build accounts, permissions, integrations, extensibility, and dashboards before you’ve proven demand. Those are expensive detours.

Build the wedge, charge for it, learn what’s missing, and only then expand into a broader product surface—pulled by real usage, not by imagination.

One way to stay disciplined is to prototype in tools that bias toward shipping. For example, Koder.ai (a vibe-coding platform) can help founders turn a narrow workflow into a working web app through chat, then iterate quickly with features like planning mode, snapshots, and rollback. When you’re ready, you can export the source code and keep scaling—without committing to a “platform-first” build on day one.

Early on, the most dangerous signal is enthusiasm without commitment. Compliments, “This is cool,” and big social numbers can feel like progress—but they don’t tell you whether the product is solving a real problem.

Prioritize behaviors that cost the customer something: time, money, reputation, or workflow change. Strong validation usually shows up as:

If you’re not seeing at least one of these, “interest” may just be politeness.

You don’t need a perfect product to test willingness to pay. Try:

The goal is simple: get customers to take a real step, not just say yes.

Treat these as weak signals:

They can support a story, but they don’t prove demand.

Pick a short window (often 14–30 days) and define the decision in advance. For example: “If we can’t get 3 paying pilot customers or 5 users who return weekly by day 30, we narrow the ICP, change the offer, or kill the idea.” Clear deadlines prevent drifting and keep learning honest.

Early on, “going broad” feels like momentum: more features, more customer types, more marketing channels. But breadth usually hides a simple problem—your startup hasn’t learned enough yet to know what works.

Most teams don’t decide to be unfocused. They slide into it:

When you aim at multiple audiences, every signal becomes noisy. A feature request might be critical for Persona A and useless for Persona B. Your messaging gets vague, your demos drift, and onboarding turns into a choose-your-own-adventure.

Costs rise in quiet ways:

Narrow focus is not about limiting ambition; it’s about creating fast, clear feedback loops.

Founders often widen scope for emotional reasons:

If things feel stuck, try this reset for the next 2–4 weeks:

Focus isn’t permanent. It’s a tool to learn faster than your runway runs out.

Winning a small market doesn’t mean you’re done—it means you’ve earned the right to grow. The key is timing: expand only after one segment is truly “locked.”

You’re ready when your message converts consistently and growth feels repeatable, not random. Practical signals include:

If you still need heroic effort to close each deal, you haven’t “won” yet—you’re still discovering.

Once you’ve nailed one wedge, expand by choosing the next closest step:

Pick the path with the fewest changes so you can reuse your positioning, product, and acquisition channels.

The common failure mode is stacking changes—new ICP and new use case and new channel. Instead, keep two things constant while you change one. For example: same persona + same workflow, but a new geography.

Treat expansion as a controlled experiment. Maintain the “core” product that your first segment loves, and test the new segment with lightweight additions:

When the new segment shows repeatable conversion and retention, you can fold what you learned back into the main product—without breaking what already works. For more on staying focused, see /blog/startup-focus.

A narrow product can look “too small” on a pitch deck, yet still be a genuinely good business—especially early on.

Y Combinator often talks about being default alive: you’re spending less than you earn (or can reliably raise), so the company can keep going without a miracle. Practically, it means you have a clear path to not running out of money—because revenue covers costs, or burn is low enough that funding isn’t a constant emergency.

A “small” market can still produce strong early revenue if the pain is intense and the buyer has budget.

If you solve one specific workflow for one specific role, you can often charge more than broad tools that feel generic. Even 50–200 customers can be meaningful when each customer pays enough to cover support, product development, and learning.

Start with value-based pricing: price against what the customer saves or earns, not your costs.

Keep it simple:

Avoid complex menus early. You want buyers to decide quickly, and you want to learn what they actually value.

You don’t need a big team or fancy tooling to win a narrow market.

Focus your budget on:

When the product is narrow, your operations can be narrow too—which makes “default alive” much easier to reach.

Starting small only works if you’re learning faster than you’re building. The easiest way to stay honest is to track a handful of “did this get better?” numbers, review them weekly, and tie them to specific customer conversations.

B2B SaaS: weekly active teams, % of accounts hitting the “aha” action, trial-to-paid conversion, churn (logo and revenue), time-to-first-value.

Consumer / prosumer app: activation rate, day-7 retention, weekly active users, invites/shared actions per user, paid conversion (if applicable).

Marketplace: successful matches per week, supply coverage (how often demand finds supply), repeat rate on both sides, take rate, cancellation rate.

Services / agency (your first wedge): qualified leads, close rate, average deal size, delivery time, gross margin, referrals.

Benchmarks are highly context-dependent, so use ranges sparingly. One safe anchor: early on, direction matters more than level—you want key rates (activation, conversion, retention) trending up as you iterate.

Write it down in a running doc so you can see the story of your progress.

If your metrics improve and these answers get sharper, you’re on the right narrow path.

Starting small isn’t “waiting to build.” It’s a way to force clarity, get real feedback, and ship something people will pay for—fast. Here’s a focused 30-day plan that keeps you moving while staying narrow.

Pick one ideal customer profile you can describe in a sentence (role, context, and constraint). Then choose one painful problem you can solve without a full product.

Write a one-sentence promise that’s specific and testable:

“We help [ICP] achieve [measurable outcome] in [timeframe] without [common headache].”

This becomes your filter. If a feature, meeting, or idea doesn’t strengthen that promise, it’s out.

Talk to 15–25 people who match your ICP. Aim for pattern-finding, not validation.

Ask about the last time they felt the pain, what they tried, what it cost (time/money), and what “fixed” would look like.

Then test pricing language early. Don’t pitch a price as a negotiation—use it as a signal:

Document exact phrases they use; those words should show up in your landing page and outreach.

Run 3–5 pilots where you do the work manually behind the scenes. The goal is to prove the outcome, not the interface.

Define one or two success metrics (e.g., time saved, fewer errors, faster turnaround) and track them per user. Iterate weekly based on what actually moved the metric.

Identify the repeatable steps you performed in pilots and turn them into the smallest “wedge” product.

Prepare one acquisition channel you can execute consistently for the next month: targeted outbound, partnerships, a niche community, or a workflow integration. Keep everything pointed at your one-sentence promise and a simple next step (book a call, start a trial, or pay for onboarding).

“Small” refers to scope, not ambition. Start with:

Ambition can stay huge, but your first version should be narrow enough to ship, learn, and improve quickly.

It’s usually “think vague.” Broad positioning (“for any team”) creates noisy feedback and slow decisions.

A narrow promise forces clarity: you either deliver the outcome for that specific user, or you don’t—and you learn faster.

Use a plain format:

Example: “It’s for independent CPAs when they onboard a new monthly client and need documents without chasing emails.”

Look for repeated, unprompted patterns:

If every conversation sounds different, your ICP (or promise) is still too broad.

Because “boring” often means immediately understandable. Familiar problems:

The advantage is speed of learning and sales, not lack of innovation.

It’s urgent, expensive, frequent, and measurable. Quick test questions:

If there’s no owner or no budget, it’s usually a weak problem.

It means manual, high-touch effort to get real users and real feedback before automating. Examples:

Be transparent about what’s manual, document repeatable steps, then automate only what you do often.

A wedge product completes one job end-to-end for a specific customer. It’s not a platform and not a partial workflow.

Define the outcome first:

Build only the must-haves required to deliver that outcome without workarounds.

Prioritize signals that cost the customer something:

Practical validation methods:

You’re ready when things feel repeatable, not heroic:

Expand with one new variable at a time:

Ignore early vanity signals like followers, page views, and vague praise.

Avoid changing ICP + use case + channel all at once.