Apr 23, 2025·8 min

Yehuda Katz and Web Frameworks: Conventions, DX, and Tooling

A practical look at Yehuda Katz’s influence on web frameworks—from Rails to Ember and modern tooling—and how conventions and DX shape adoption.

A practical look at Yehuda Katz’s influence on web frameworks—from Rails to Ember and modern tooling—and how conventions and DX shape adoption.

Framework adoption is rarely a pure feature comparison. Teams stick with tools that feel easy to live with—not because they have more capabilities, but because they reduce daily friction.

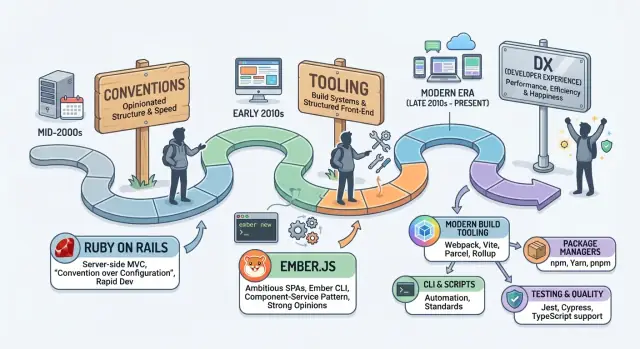

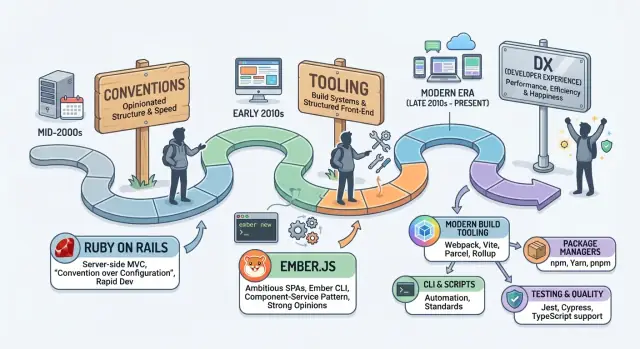

The arc of Yehuda Katz’s work—through Ruby on Rails, the Ember.js era, and today’s tooling-heavy JavaScript world—is a useful lens for understanding what makes a framework “click” with real teams.

Many frameworks can render pages, fetch data, and structure code. The difference shows up between the milestones: creating a project, adding a route, handling a confusing error, upgrading six months later, or onboarding a new teammate. Frameworks win mindshare when they smooth those moments with sensible defaults and a clear way of doing things.

We’ll look at three chapters:

This isn’t a biography, and it isn’t a deep technical history. It’s about what these chapters reveal about how frameworks earn trust.

“Developer experience” (DX) can sound abstract, but it’s concrete in practice. It includes:

If you’ve ever wondered why one framework spreads inside companies while another stalls, this article is for you. You don’t need to be an expert: we’ll focus on practical signals—conventions, tooling, and upgrade paths—that explain adoption in the real world, not just on paper.

Most teams don’t adopt a framework because of one killer API. They adopt it because the framework standardizes hundreds of tiny decisions—so the team can stop debating and start shipping.

Conventions are default answers to common questions: Where does this file go? What should it be called? How do pages find data? In Rails, you don’t renegotiate folder structure on every project—you follow it.

A simple example:

app/controllers/users_controller.rbapp/models/user.rbapp/views/users/show.html.erbThe names and folders aren’t just tidy; they’re how the framework wires things together.

Ember carried the same idea forward on the frontend: a predictable project layout and naming scheme that makes the app feel navigable even when you didn’t write it.

Conventions reduce decision fatigue. When there’s a “normal way,” teams spend less time designing internal standards and more time building features.

They also make onboarding faster. New hires can recognize patterns from prior jobs, and juniors can follow tutorials without constantly hitting “it depends.” Shared patterns create a common mental model across projects.

Conventions can limit flexibility. Sometimes you want a different folder layout or a custom workflow, and frameworks like Rails or Ember can push you toward “the Rails/Ember way.” The upside is consistency; the cost is learning the house rules.

The bigger the community, the more valuable conventions become. Tutorials assume the same structure. Hiring gets easier because candidates already know where to look. Even code reviews improve: discussions shift from “how should we do this?” to “did we follow the standard?”

Rails mattered because it treated “building a web app” as a complete job, not a pile of parts. Instead of asking every team to assemble a stack from scratch, Rails shipped integrated defaults for the most common needs: routing, controllers, views, database migrations, testing patterns, and a clear way to organize code.

For a huge slice of CRUD-style applications, you didn’t have to design the architecture before writing your first feature—you could start building immediately.

A big part of that speed was the combination of generators and conventions. Rails didn’t just provide APIs; it provided a project shape.

When you generated a model or scaffold, Rails created files in predictable locations, wired up naming conventions, and nudged you toward a shared workflow. That consistency had two practical effects:

In other words, folder structure and naming rules weren’t cosmetic—they were a coordination tool.

Rails reduced time-to-first-feature by eliminating early decisions that rarely create product value. You didn’t need to debate which ORM to use, how to structure controllers, or how to create migrations. The framework made those calls, and because the defaults were coherent, the path from an idea to a working endpoint was short.

That experience shaped expectations: frameworks weren’t only about runtime behavior; they were about getting started quickly and staying productive as the app grew.

Rails also helped normalize the idea that tooling is part of the product. The command line wasn’t an optional extra—it was the front door. Generators, migrations, and standardized tasks made the framework feel guided rather than merely configurable.

That “batteries-included” philosophy later influenced frontend thinking as well, including Yehuda Katz’s emphasis that adoption often follows the tools and conventions that make a framework feel complete.

As Rails popularized the idea of “a framework that ships with a plan,” frontend development was still often a pile of parts. Teams mixed jQuery plugins, templating libraries, ad‑hoc AJAX calls, and hand-rolled build steps. It worked—until the app grew.

Then every new screen required more manual wiring: syncing URLs to views, keeping state consistent, deciding where data lived, and teaching every new developer the project’s private conventions.

Single-page apps made the browser a real application runtime, but early tooling didn’t offer a shared structure. The result was uneven codebases where:

Ember emerged to treat the frontend like a first-class application layer—not just a set of UI widgets. Instead of saying “pick your own everything,” it offered a coherent set of defaults and a way for teams to align.

At a high level, Ember emphasized:

Ember’s pitch wasn’t novelty—it was stability and shared understanding. When the framework defines the “happy path,” teams spend less time debating architecture and more time shipping features.

That predictability matters most in apps that live for years, where onboarding, upgrades, and consistent patterns are as valuable as raw flexibility.

Frameworks aren’t just code you install once; they’re a relationship you maintain. That’s why Ember put unusual emphasis on stability: predictable releases, clear deprecation warnings, and documented upgrade paths. The goal wasn’t to freeze innovation—it was to make change something teams could plan for instead of something that “happens to them.”

For many teams, the biggest cost of a framework isn’t the first build—it’s the third year. When a framework signals that upgrades will be understandable and incremental, it reduces a practical fear: getting stuck on an old version because moving forward feels risky.

No framework can honestly guarantee painless upgrades. What matters is the philosophy and the habits: communicating intent early, providing migration guidance, and treating backward compatibility as a user-facing feature.

Ember popularized an RFC-style process for proposing and discussing changes in public. An RFC approach helps framework evolution scale because it:

Good governance turns a framework into something closer to a product with a roadmap, not a grab bag of APIs.

A framework isn’t just an API surface—it’s the first 30 minutes a new developer spends with it. That’s why the CLI became the “front door” for framework adoption: it turns a vague promise (“easy to start”) into a repeatable experience.

When a CLI lets you create, run, test, and build a project with predictable commands, it removes the biggest early failure mode: setup uncertainty.

Typical moments that shape trust look like this:

rails new … or ember new …rails server, ember serverails test, ember testrails assets:precompile, ember buildThe specific commands differ, but the promise is the same: “You don’t have to assemble your own starter kit.”

Framework tooling is a bundle of practical decisions that teams would otherwise debate and reconfigure on every project:

Rails popularized this feeling early with generators and conventions that made new apps look familiar. Ember doubled down with ember-cli, where the command line became the coordinating layer for the whole project.

Good defaults reduce the need for long internal docs and copy-paste configuration. Instead of “follow these 18 steps,” onboarding becomes “clone the repo and run two commands.” That means faster ramp-up, fewer machine-specific environment issues, and fewer subtle differences between projects.

The same adoption dynamic shows up beyond classic CLIs. Platforms like Koder.ai take the “front door” idea further by letting teams describe an app in chat and generate a structured codebase (for example, React on the frontend, Go + PostgreSQL on the backend, and Flutter for mobile) with deployment, hosting, and source-code export available when needed.

The point isn’t that chat replaces frameworks—it’s that onboarding and repeatability are now product features. Whether the entry point is a CLI or a chat-driven builder, the winning tools reduce setup ambiguity and keep teams on a consistent path.

DX isn’t a vibe. It’s what you experience while building features, fixing bugs, and onboarding teammates—and those signals often decide which framework a team keeps long after the initial excitement.

A framework’s DX shows up in small, repeated moments:

These are the things that turn learning into progress instead of friction.

A big part of adoption is the “pit of success”: the right thing should also be the easiest thing. When conventions steer you toward secure defaults, consistent patterns, and performance-friendly setups, teams make fewer accidental mistakes.

This is why conventions can feel like freedom. They reduce the number of decisions you need to make before you can write the code that matters.

Docs aren’t an afterthought in DX; they’re a core feature. High-quality documentation includes:

When the docs are strong, teams can self-serve answers instead of relying on tribal knowledge.

Early on, a team might tolerate “clever” setups. As the codebase expands, consistency becomes a survival skill: predictable patterns make reviews faster, bugs easier to trace, and onboarding less risky.

Over time, teams often choose the framework (or platform) that keeps day-to-day work calm—not the one that offers the most options.

When tooling is fragmented, the first “feature” your team ships is a pile of decisions. Which router? Which build system? Which testing setup? How do styles work? Where do environment variables live?

None of these choices are inherently bad—but the combinations can be. Fragmentation increases mismatch risk: packages assume different build outputs, plugins overlap, and “best practices” conflict. Two developers can start the same project and end up with materially different setups.

This is why “standard stacks” earn mindshare. A standard stack is less about being perfect and more about being predictable: a default router, a default testing story, a default folder structure, and a default upgrade path.

Predictability has compounding benefits:

That’s a big part of what people admired in Rails and later in Ember’s approach: a shared vocabulary. You don’t just learn a framework—you learn “the way” projects are usually assembled.

Flexibility gives teams room to optimize: choose the best-in-class library for a specific need, swap parts out, or adopt new ideas early. For experienced teams with strong internal standards, modularity can be a strength.

Consistency, though, is what makes a framework feel like a product. A consistent stack reduces the number of local rules you need to invent, and it lowers the cost of switching teams or maintaining older projects.

Adoption isn’t only about technical merit. Standards help teams ship with less debate, and shipping builds confidence. When a framework’s conventions remove uncertainty, it’s easier to justify the choice to stakeholders, easier to hire for (because skills transfer between companies), and easier for the community to teach.

In other words: standards win mindshare because they shrink the “decision surface area” of building web apps—so more energy goes into the app itself, not the scaffolding around it.

Frameworks used to feel “complete” if they gave you routing, templates, and a decent folder structure. Then the center of gravity moved: bundlers, compilers, package managers, and deployment pipelines became part of everyday work.

Instead of asking “Which framework should we use?”, teams started asking “What toolchain are we signing up for?”

Modern apps aren’t one or two files anymore. They’re hundreds: components, styles, translations, images, and third‑party packages. Build tooling is the machinery that turns all of that into something a browser can load efficiently.

A simple way to explain it: you write many small files because it’s easier to maintain, and the build step turns them into a small number of optimized files so users download a fast app.

Build tools sit in the critical path for:

Once this became standard, frameworks had to provide more than APIs—they needed a supported path from source code to production output.

The upside is speed and scale. The cost is complexity: configuration, plugin versions, compiler quirks, and subtle breaking changes.

That’s why “batteries included” increasingly means stable build defaults, sane upgrade paths, and tooling that fails with understandable errors—not just a nice component model.

Upgrading a framework isn’t just a “maintenance chore.” For most teams, it’s the moment where a framework either earns long-term trust—or gets quietly replaced at the next rewrite.

When upgrades go wrong, the costs aren’t abstract. They show up as schedule slips, unpredictable regressions, and a growing fear of touching anything.

Common sources of friction include:

That last point is where conventions matter: a framework that defines “the standard way” tends to create healthier upgrade paths because more of the ecosystem moves in sync.

DX isn’t only about how fast you can start a new app. It’s also how safe it feels to keep an existing app current. Predictable upgrades reduce cognitive load: teams spend less time guessing what changed and more time shipping.

This is one reason frameworks influenced by Yehuda Katz’s thinking put real product effort into upgrade ergonomics: clear versioning policies, stable defaults, and tooling that makes change less scary.

The best upgrade stories are intentionally designed. Practices that consistently help:

When this work is done well, upgrading becomes a routine habit instead of a periodic crisis.

Teams adopt what they believe they can keep updated. If upgrades feel like roulette, they’ll freeze versions, accumulate risk, and eventually plan an exit.

If upgrades feel managed—documented, automated, incremental—they’ll invest deeper, because the framework feels like a partner rather than a moving target.

“Integrated” frameworks (think Rails, or Ember at its most opinionated) try to make the common path feel like one product. A “modular stack” assembles best-of-breed pieces—router, state/data layer, build tool, test runner—into something tailored.

Good integration isn’t about having more features; it’s about fewer seams.

When those parts are designed together, teams spend less time debating patterns and more time shipping.

Modular stacks often start small and feel flexible. The cost shows up later as glue code and one-off decisions: bespoke folder structures, custom middleware chains, homegrown conventions for data fetching, and ad-hoc test utilities.

Each new project repeats the same “how do we do X here?” conversations, and onboarding becomes a scavenger hunt through past commits.

Modularity is great when you need a lighter footprint, highly specific requirements, or you’re integrating into an existing system. It also helps teams that already have strong internal standards and can enforce them consistently.

Consider: team size (more people = higher coordination cost), app lifetime (years favor integration), expertise (can you maintain your own conventions?), and how many projects you expect to build with the same approach.

Framework adoption is less about what’s “best” and more about what your team can reliably ship with six months from now. Yehuda Katz’s work (from Rails conventions to Ember’s tooling) highlights the same theme: consistency beats novelty when you’re building real products.

Use this quick set of questions when comparing an integrated framework to a lighter stack:

Teams with mixed experience levels, products with long lifetimes, and organizations that value predictable onboarding usually win with conventions. You’re paying for fewer decisions, more shared vocabulary, and a smoother upgrade story.

If you’re experimenting, building a small app, or you have senior engineers who enjoy composing custom tooling, a modular stack can be faster. Just be honest about the long-term cost: you become the integrator and the maintainer.

Conventions, DX, and tooling aren’t “nice-to-haves.” They multiply adoption by reducing uncertainty—especially during setup, daily work, and upgrades.

Choose the option your team can repeat, not the one that only your experts can rescue. And if your bottleneck is less “which framework” and more “how do we consistently ship full-stack software quickly,” a guided, convention-heavy workflow—whether via a framework CLI or a platform like Koder.ai—can be the difference between continuous delivery and perpetual scaffolding.

Framework adoption is often decided by day-to-day friction, not headline features. Teams notice whether setup is smooth, defaults are coherent, docs answer common workflows, errors are actionable, and upgrades feel safe over time.

If those moments are predictable, a framework tends to “stick” inside an organization.

Conventions are default answers to recurring questions like file placement, naming, and “the normal way” to build common features.

Practical benefits:

The trade-off is less freedom to invent your own architecture without friction.

A batteries-included framework ships a complete path for typical app work: routing, structure, generators, testing patterns, and a guided workflow.

In practice, it means you can go from “new project” to “first feature” without assembling a custom stack or writing a lot of glue code up front.

As frontend apps grew, teams started suffering from ad-hoc structure: improvised routing, inconsistent data fetching, and one-off project conventions.

Ember’s pitch was predictability:

That makes maintenance and onboarding easier when the app is expected to last years.

Stability is a product feature because most costs show up later, during the second and third year of a codebase.

Signals that create trust include:

These reduce the fear of getting stuck on an old version.

The CLI is often the “front door” because it turns promises into a repeatable workflow:

A good CLI reduces setup uncertainty and keeps projects aligned over time.

Practical DX shows up in small moments you repeat constantly:

Teams usually prefer the framework that keeps daily work calm and predictable.

Choice overload happens when you must pick and integrate everything yourself: router, build system, testing setup, data patterns, and folder structure.

It increases risk because combinations can conflict, and two projects can end up with incompatible “standards.” A standard stack reduces variance, making onboarding, reviews, and debugging more consistent across teams.

Modern frameworks are judged by the toolchain they commit you to: bundling, modules, performance optimizations, and deploy artifacts.

Since build tooling is in the critical path for performance and deployment, frameworks increasingly need:

Choose integrated when you value predictability and long-term maintenance; choose modular when you need flexibility and can enforce your own standards.

A practical decision checklist:

If you’ll build multiple apps the same way, a consistent “product-like” framework usually pays off.