Sep 23, 2025·8 min

ZSTD vs Brotli vs GZIP: Choosing API Compression

Compare ZSTD, Brotli, and GZIP for APIs: speed, ratio, CPU cost, and practical defaults for JSON and binary payloads in production.

Compare ZSTD, Brotli, and GZIP for APIs: speed, ratio, CPU cost, and practical defaults for JSON and binary payloads in production.

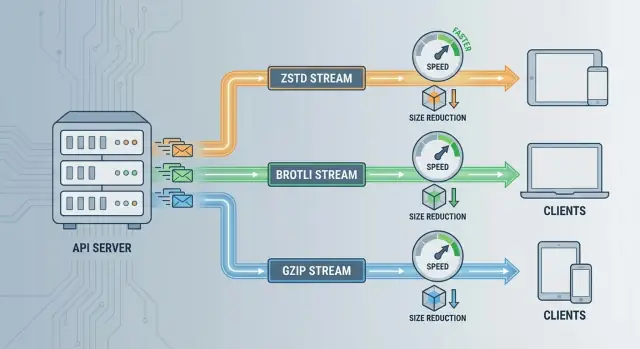

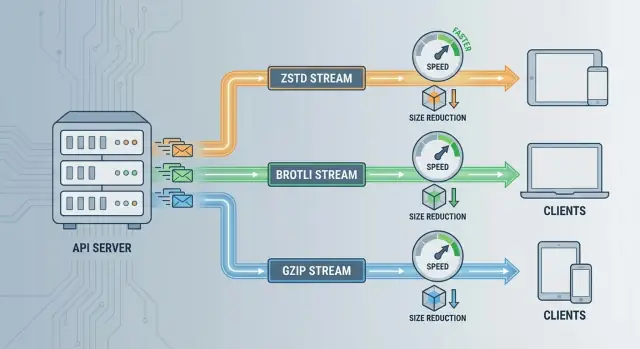

API response compression means your server encodes the response body (often JSON) into a smaller byte stream before sending it over the network. The client (browser, mobile app, SDK, or another service) then decompresses it. Over HTTP, this is negotiated through headers like Accept-Encoding (what the client supports) and Content-Encoding (what the server chose).

Compression mainly buys you three things:

The trade-off is straightforward: compression saves bandwidth but costs CPU (compress/decompress) and sometimes memory (buffers). Whether it’s worth it depends on your bottleneck.

Compression tends to shine when responses are:

If you return large JSON lists (catalogs, search results, analytics), compression is often one of the easiest wins.

Compression is often a poor use of CPU when responses are:

When choosing between ZSTD vs Brotli vs GZIP for API compression, the practical decision usually comes down to:

Everything else in this article is about balancing those three for your particular API and traffic patterns.

All three reduce payload size, but they optimize for different constraints—speed, compression ratio, and compatibility.

ZSTD speed: Great when your API is sensitive to tail latency or your servers are CPU-bound. It can compress fast enough that the overhead is often negligible compared to network time—especially for medium-to-large JSON responses.

Brotli compression ratio: Best when bandwidth is the primary constraint (mobile clients, expensive egress, CDN-heavy delivery) and responses are mostly text. Smaller payloads can be worth it even if compression takes longer.

GZIP compatibility: Best when you need maximum client support with minimal negotiation risk (older SDKs, embedded clients, legacy proxies). It’s a safe baseline even if it isn’t the top performer.

Compression “levels” are presets that trade CPU time for smaller output:

Decompression is usually much cheaper than compression for all three, but very high levels can still increase client CPU/battery—especially important for mobile.

Compression is often sold as “smaller responses = faster APIs.” That’s frequently true on slow or expensive networks—but it’s not automatic. If compression adds enough server CPU time, you can end up with slower requests despite fewer bytes on the wire.

It helps to separate two costs:

A high compression ratio can reduce transfer time, but if compression adds (say) 15–30 ms of CPU per response, you may lose more time than you save—especially on fast connections.

Under load, compression can hurt p95/p99 latency more than p50. When CPU usage spikes, requests queue. Queueing amplifies small per-request costs into big delays—average latency looks fine, but the slowest users suffer.

Don’t guess. Run an A/B test or staged rollout and compare:

Test with realistic traffic patterns and payloads. The “best” compression level is the one that reduces total time, not just bytes.

Compression isn’t “free”—it shifts work from the network to CPU and memory on both ends. In APIs, that shows up as higher request handling time, larger memory footprints, and sometimes client-side slowdowns.

Most CPU is spent compressing responses. Compression finds patterns, builds state/dictionaries, and writes encoded output.

Decompression is typically cheaper, but still relevant:

If your API is already CPU-bound (busy app servers, heavy auth, expensive queries), turning on a high compression level can increase tail latency even if payloads shrink.

Compression can increase memory use in a few ways:

In containerized environments, higher peak memory can translate into more OOM kills or tighter limits that reduce density.

Compression adds CPU cycles per response, reducing throughput per instance. That can trigger autoscaling sooner, raising costs. A common pattern: bandwidth drops, but CPU spend rises—so the right choice depends on which resource is scarce for you.

On mobile or low-power devices, decompression competes with rendering, JavaScript execution, and battery. A format that saves a few KB but takes longer to decompress can feel slower, particularly when “time to usable data” matters.

Zstandard (ZSTD) is a modern compression format designed to deliver a strong compression ratio without slowing your API down. For many JSON-heavy APIs, it’s a strong “default”: noticeably smaller responses than GZIP at similar or lower latency, plus very fast decompression on clients.

ZSTD is most valuable when you care about end-to-end time, not just smallest bytes. It tends to compress quickly and decompress extremely quickly—useful for APIs where every millisecond of CPU time competes with request handling.

It also performs well across a wide range of payload sizes: small-to-medium JSON often sees meaningful gains, while large responses can benefit even more.

For most APIs, start with low levels (commonly level 1–3). These often provide the best latency/size trade-off.

Use higher levels only when:

A pragmatic approach is a low global default, then selectively increase the level for a few “big response” endpoints.

ZSTD supports streaming, which can reduce peak memory and start sending data sooner for large responses.

Dictionary mode can be a big win for APIs that return many similar objects (repeated keys, stable schemas). It’s most effective when:

Server-side support is straightforward in many stacks, but client compatibility can be the deciding factor. Some HTTP clients, proxies, and gateways still don’t advertise or accept Content-Encoding: zstd by default.

If you serve third-party consumers, keep a fallback (usually GZIP) and enable ZSTD only when Accept-Encoding clearly includes it.

Brotli is designed to squeeze text extremely well. On JSON, HTML, and other “wordy” payloads, it often beats GZIP on compression ratio—especially at higher compression levels.

Text-heavy responses are Brotli’s sweet spot. If your API sends large JSON documents (catalogs, search results, configuration blobs), Brotli can cut bytes noticeably, which helps on slow networks and can reduce egress cost.

Brotli is also strong when you can compress once and serve many times (cacheable responses, versioned resources). In those cases, high-level Brotli can be worth it because the CPU cost is amortized.

For dynamic API responses (generated on every request), Brotli’s best ratios often require higher levels that can be CPU-expensive and add latency. Once you account for compression time, the real-world win over ZSTD (or even a well-tuned GZIP) may be smaller than expected.

It’s also less compelling for payloads that don’t compress well (already-compressed data, many binary formats). In those cases you just burn CPU.

Browsers generally support Brotli well over HTTPS, which is why it’s popular for web traffic. For non-browser API clients (mobile SDKs, IoT devices, older HTTP stacks), support can be inconsistent—so negotiate correctly via Accept-Encoding and keep a fallback (typically GZIP).

GZIP remains the default answer for API compression because it’s the most universally supported option. Nearly every HTTP client, browser, proxy, and gateway understands Content-Encoding: gzip, and that predictability matters when you don’t fully control what sits between your server and your users.

The advantage isn’t that GZIP is “best”—it’s that it’s rarely the wrong choice. Many organizations have years of operational experience with it, sensible defaults in their web servers, and fewer surprises with intermediaries that might mishandle newer encodings.

For API payloads (often JSON), mid-to-low compression levels tend to be the sweet spot. Levels like 1–6 commonly deliver most of the size reduction while keeping CPU reasonable.

Very high levels (8–9) can squeeze out a bit more, but the extra CPU time usually isn’t worth it for dynamic request/response traffic where latency matters.

On modern hardware, GZIP is generally slower than ZSTD at similar compression ratios, and it often can’t match Brotli’s best ratios on text payloads. In real API workloads, that typically means:

If you have to support older clients, embedded devices, strict corporate proxies, or legacy gateways, GZIP is the safest bet. Some intermediaries will strip unknown encodings, fail to pass them through, or break negotiation—issues that are much less common with GZIP.

If your environment is mixed or uncertain, starting with GZIP (and adding ZSTD/Brotli only where you control the full path) is often the most reliable rollout strategy.

Compression wins aren’t just about the algorithm. The biggest driver is the kind of data you send. Some payloads shrink dramatically with ZSTD, Brotli, or GZIP; others barely move and just burn CPU.

Text-heavy responses tend to compress extremely well because they contain repeated keys, whitespace, and predictable patterns.

As a rule, the more repetition and structure, the better the compression ratio.

Binary formats like Protocol Buffers and MessagePack are more compact than JSON, but they aren’t “random.” They can still contain repeated tags, similar record layouts, and predictable sequences.

That means they’re frequently still compressible, especially for larger responses or list-heavy endpoints. The only reliable answer is to test with your real traffic: same endpoint, same data, compression on/off, and compare both size and latency.

Many formats are already compressed internally. Applying HTTP response compression on top typically gives tiny savings and can increase response time.

For these, it’s common to disable compression by content type.

A straightforward approach is to compress only when responses cross a minimum size.

Content-Encoding.This keeps CPU focused on payloads where compression actually reduces bandwidth and improves end-to-end performance.

Compression only works smoothly when clients and servers agree on an encoding. That agreement happens through Accept-Encoding (sent by the client) and Content-Encoding (sent by the server).

A client advertises what it can decode:

GET /v1/orders HTTP/1.1

Host: api.example

Accept-Encoding: zstd, br, gzip

The server picks one and declares what it used:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: application/json

Content-Encoding: zstd

If the client sends Accept-Encoding: gzip and you respond with Content-Encoding: br, that client may fail to parse the body. If the client sends no Accept-Encoding, the safest default is to send no compression.

A practical order for APIs is often:

zstd first (great speed/ratio balance)br (often smaller, sometimes slower)gzip (widest compatibility)In other words: zstd > br > gzip.

Don’t treat this as universal: if your traffic is mostly browsers, br may deserve higher priority; if you have older mobile clients, gzip might be the safest “best” choice.

If a response can be served in multiple encodings, add:

Vary: Accept-Encoding

Without it, a CDN or proxy might cache the gzip (or zstd) version and incorrectly serve it to a client that didn’t ask for (or can’t handle) that encoding.

Some clients claim support but have buggy decoders. To stay resilient:

zstd, temporarily fall back to gzip.Negotiation is less about squeezing every byte and more about never breaking a client.

API compression doesn’t run in a vacuum. Your transport protocol, TLS overhead, and any CDN or gateway in between can change the real-world outcome—or even break things if misconfigured.

With HTTP/2, multiple requests share a single TCP connection. That reduces connection overhead, but packet loss can stall all streams due to TCP head-of-line blocking. Compression can help by shrinking response bodies, reducing the amount of data “stuck” behind a loss event.

HTTP/3 runs over QUIC (UDP) and avoids TCP-level head-of-line blocking between streams. Payload size still matters, but the loss penalty is often less dramatic per connection. In practice, compression remains valuable—expect benefits to show up more as bandwidth savings and faster “time to last byte” than as dramatic latency drops.

TLS already consumes CPU (handshakes, encryption/decryption). Adding compression (especially at high levels) can push you over CPU limits during spikes. This is why “fast compression with decent ratio” settings often outperform “maximum ratio” in production.

Some CDNs/gateways automatically compress certain MIME types, while others pass through what the origin sends. A few may normalize or even remove Content-Encoding if misconfigured.

Verify behavior per route, and ensure Vary: Accept-Encoding is preserved so caches don’t serve a compressed variant to a client that didn’t ask for it.

If you cache at the edge, consider storing separate variants per encoding (gzip/br/zstd) rather than recompressing on every hit. If you cache at origin, you may still want the edge to negotiate and cache multiple encodings.

The key is consistency: correct Content-Encoding, correct Vary, and clear ownership of where compression happens.

For browser-facing APIs, prefer Brotli when the client advertises it (Accept-Encoding: br). Browsers generally decode Brotli efficiently, and it often delivers better size reduction on text responses.

For internal service-to-service APIs, default to ZSTD when both sides are under your control. It’s typically faster at similar or better ratios than GZIP, and negotiation is straightforward.

For public APIs used by diverse SDKs, keep GZIP as the universal baseline and optionally add ZSTD as an opt-in for clients that explicitly support it. That avoids breaking older HTTP stacks.

Start with levels that are easy to measure and unlikely to surprise you:

If you need a stronger ratio, validate with production-like payload samples and track p95/p99 latency before raising levels.

Compressing tiny responses can cost more CPU than it saves on the wire. A practical starting point:

Tune by comparing: (1) bytes saved, (2) added server time, (3) end-to-end latency change.

Roll out compression behind a feature flag, then add per-route config (enable for /v1/search, disable for already-small endpoints). Provide a client opt-out using Accept-Encoding: identity for troubleshooting and edge clients. Always include Vary: Accept-Encoding to keep caches correct.

If you’re generating APIs quickly (for example, spinning up React frontends with Go + PostgreSQL backends, then iterating based on real traffic), compression becomes one of those “small config, big impact” knobs.

On Koder.ai, teams often reach this point earlier because they can prototype and deploy full-stack apps fast, then tune production behavior (including response compression and cache headers) once endpoints and payload shapes stabilize. The practical takeaway is the same: treat compression as a performance feature, ship it behind a flag, and measure p95/p99 before declaring victory.

Compression changes are easy to ship and surprisingly easy to get wrong. Treat it like a production feature: roll out gradually, measure impact, and keep rollback simple.

Start with a canary: enable the new Content-Encoding (for example, zstd) for a small slice of traffic or a single internal client.

Then ramp gradually (e.g., 1% → 5% → 25% → 50% → 100%), pausing if key metrics move in the wrong direction.

Keep an easy rollback path:

gzip).Track compression as both a performance and reliability change:

4xx/5xx, client decode errors, and timeouts.When something breaks, these are the usual suspects:

Content-Encoding set but body is not compressed (or vice versa).Accept-Encoding, or returning an encoding the client didn’t advertise.Content-Length, or proxy/CDN interference.Spell out supported encodings in your docs, including examples:

Accept-Encoding: zstd, br, gzipContent-Encoding: zstd (or fallback)If you ship SDKs, add small, copy-pasteable decode examples and clearly state any minimum versions that support Brotli or Zstandard.

Use response compression when responses are text-heavy (JSON/GraphQL/XML/HTML), medium-to-large, and your users are on slow/expensive networks or you pay meaningful egress costs. Skip it (or use a high threshold) for tiny responses, already-compressed media (JPEG/MP4/ZIP/PDF), and CPU-bound services where extra per-request work will hurt p95/p99 latency.

Because it trades bandwidth for CPU (and sometimes memory). Compression time can delay when the server starts sending bytes (TTFB), and under load it can amplify queueing—often hurting tail latency even if average latency improves. The “best” setting is the one that reduces end-to-end time, not just payload size.

A practical default priority for many APIs is:

zstd first (fast, good ratio)br (often smallest for text, can cost more CPU)gzip (widest compatibility)Always base the final choice on what the client advertises in , and keep a safe fallback (usually or ).

Start low and measure.

Use a minimum response size threshold so you don’t burn CPU on tiny payloads.

Tune per endpoint by comparing bytes saved vs added server time and the impact on p50/p95/p99 latency.

Focus on content types that are structured and repetitive:

Compression should follow HTTP negotiation:

Accept-Encoding (e.g., zstd, br, gzip)Content-EncodingIf the client doesn’t send , the safest response is typically . Never return that the client didn’t advertise, or you risk client failures.

Add:

Vary: Accept-EncodingThis prevents CDNs/proxies from caching (say) a gzip response and incorrectly serving it to a client that didn’t request or can’t decode gzip (or zstd/br). If you support multiple encodings, this header is essential for correct caching behavior.

Common failure modes include:

Roll it out like a performance feature:

Accept-EncodinggzipidentityHigher levels usually give diminishing size wins but can spike CPU and worsen p95/p99.

A common approach is to enable compression only for text-like Content-Type values and disable it for known already-compressed formats.

Accept-EncodingContent-EncodingContent-Encoding says gzip but body isn’t gzip)Accept-Encoding)Content-Length when streaming/compressingWhen debugging, capture raw response headers and verify decompression with a known-good tool/client.

If tail latency rises under load, lower the level, increase the threshold, or switch to a faster codec (often ZSTD).